Typhoon Haiyan: Tacloban survivors wait for aid

- Published

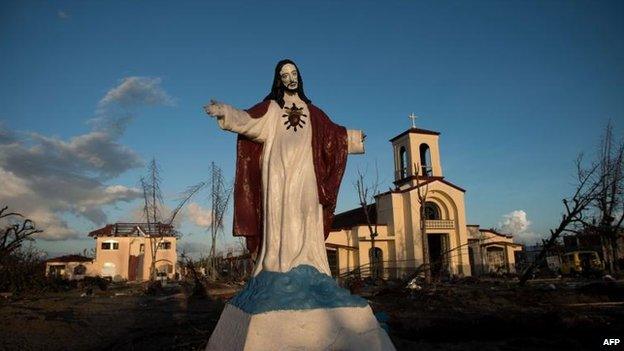

Much of the city of Tacloban has been destroyed

One week after Typhoon Haiyan ravaged the central Philippines, aid has begun to arrive in the city of Tacloban, one of the worst-affected areas. But as the BBC's Rajesh Mirchandani found out, it has yet to reach many of those most in need.

The body bags lay by the side of the main road.

Fifteen of them, I counted. Two were child-sized.

Somebody had clearly gone to the trouble of giving these poor wretches some shred of dignity - a shroud of dignity?

Except it wasn't, really. Why bag them, move them and leave - why not take them away? It's a sign of the chaos that has engulfed the city of Tacloban, just as the wave did one week earlier.

Stoical

Along this particular stretch of wreckage, people casually stepped over the body bags and continued past.

Many crossed the street and joined the end of a long line, maybe 1,000 long, waiting in the hope of food aid. They'd heard it was due to be distributed at the Tacloban Convention Centre - itself damaged, but still a new home for thousands.

There was no sense of anger in that line of hungry faces, no simmering tension. In the Philippines they call this "bahala na", which roughly translates as "come what may" and suggests a stoical, good-natured attitude.

About 300 people have been buried in a mass grave beside this statue in the Palo suburb of Tacloban

Aid, some of it delivered from helicopters launched off a US aircraft carrier, is now reaching Tacloban

Thousands of people in Tacloban have been left homeless

The storm has now passed but the damage will take years to repair

As they sheltered under umbrellas from the brutal tropical sun, their faces displayed just tiredness and resignation - apart from the many children, who were playful and engaging.

But Abigail Salis' two toddlers were not there. They were being looked after by their grandmother in the ruins of a collapsed office building across the street - their new home.

The typhoon made Abigail a widow and now she was worried about how she would look after her children. They had survived on biscuits and a little water since the storm. They had eaten nothing on the day we met.

Abigail told me she had not been in line for long, maybe 30 minutes. Ahead of her, the line snaked for more than 100m (110 yards).

Inside the gates of the Convention Centre, the line became more of a gathering and where it ended there was nothing. Not a food distribution point, not a government or UN truck, not even a bag of rice.

People at the front told me they had been waiting for four hours. One woman said she had not had any water since 7am the day before.

The Dopa family, including 11-year-old Cherry Mae and Nathaniel, 9, squatted on the concrete and huddled for shade.

"What are you most worried about?" I asked Mrs Dopa.

"My children's education," she told me. She wore a t-shirt with the slogan "Fan of books".

While we were at the Convention Centre no food arrived, let alone was given out to people.

Yet parked outside, within sight of those waiting, were two flat-bed trucks laden with food supplies, donated by a private company. They told me that there was no-one to coordinate their donations, so they just waited.

And the people still went hungry.

Bahala na.