Bangladesh hanging of Abdul Kader Mullah risks derailing elections

- Published

Awami League activists celebrate after hearing the news of Abdul Kader Mullah's execution in Dhaka

Bangladesh has entered uncharted territory with the hanging of a top Islamist leader for crimes against humanity committed during the country's independence war in 1971.

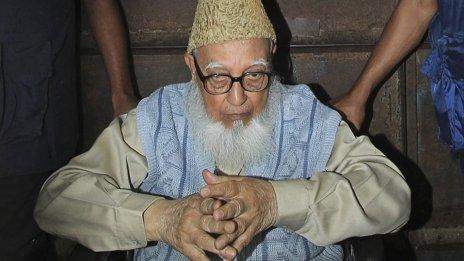

The execution of Abdul Kader Mullah came despite dire warnings of civil strife, and in defiance of international calls to stay the execution.

Mullah, a senior leader of Bangladesh's largest Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, was convicted on five counts of murder and genocide by the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), a domestic court set up three years ago.

The hanging marks a watershed in the country's short but often bloody history. This is the first time a senior politician has been tried in a civil court and hanged for offences committed in 1971.

The ICT has so far convicted 10 people, eight of whom have been given the death sentence.

The ICT said Mullah's crimes included the massacre of unarmed civilians

'Set the country ablaze'

The government has clearly taken a calculated risk in carrying out the sentence at a time when the country is already in the grip of nearly a month-long opposition strike.

A few weeks earlier, Jamaat leaders said they would ''set the country ablaze'' if Mullah was executed.

During the past few days, thousands of mobile phone users have received messages from an unidentified number, warning it would lead to civil war.

The government of Sheikh Hasina had also come under pressure not to carry out the death sentence from the UK, US, the EU and the UN's human rights body. They worry that the hanging could derail delicate negotiations over upcoming general elections scheduled for 5 January.

The government's determination to see through Mullah's trial to the bitter end has also generated great debate in Bangladesh.

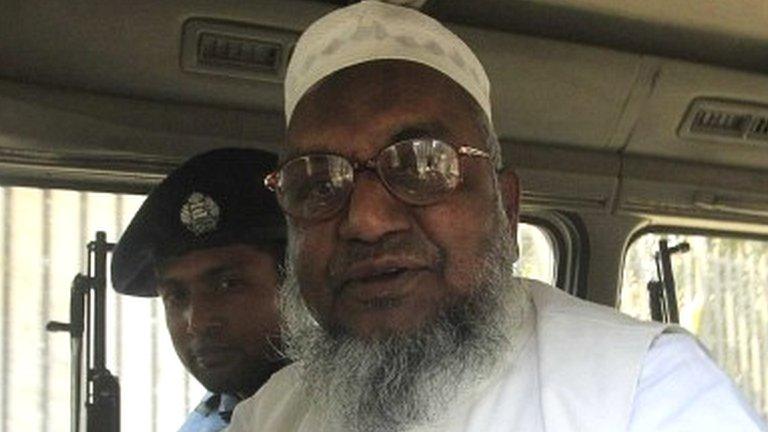

Bangladesh police detain a Jamaat-e-Islami activist during a protest in Dhaka in February

Jamaat-e-Islami is aligned to the country's largest opposition party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Jamaat has claimed its leaders were being targeted for trial as part of the governing Awami League's efforts to destroy the opposition.

Muted reaction

Jamaat supporters unleashed widespread violence in February when their charismatic leader Delwar Hossain Sayeedi was sentenced to death. Nearly 100 people died in nearly a week of clashes.

However, initial reaction to Mullah's execution has been fairly muted. There have been reports of scattered violence and small-scale protests in some parts of the country, but this was part of a wave of agitation that was already in progress.

For nearly a month, the entire country has been under a rail and road blockade by the BNP and its allies. It has cut off routes between Dhaka and much of the country, including the vital port city of Chittagong.

The BNP has rejected the 5 January date set for general elections, and called for action to bring down Ms Hasina's interim government.

The BNP and its allies want a neutral caretaker government to oversee the polls, arguing that Ms Hasina cannot be trusted to deliver free and fair elections.

Opinion polls, including one commissioned by the Awami League, show overwhelming public support for elections under a neutral government. But at the same time, there is great deal of public disquiet over the opposition's agitation programme, which has left at least 50 people dead since 26 November.

Onlookers gather at the scene of a train derailment in the district of Gaibandha

Most of the dead are ordinary citizens travelling on buses, trains or other public transport, attacked by suspected opposition activists with petrol bombs.

The deepening crisis has generated a speculation about the possibility of a state of emergency being declared.

During a similar crisis in 2007, the military stepped in and installed a caretaker government to carry out political reforms. They failed in that task, but managed to steer the country back to constitutional rule through largely free and fair elections.

The Awami League came to power in 2009 through a landslide victory.

There are fears that, if Mullah's hanging does trigger violent protests on top of the blockades and strikes, then the government would find reason to call in the army. This would end hopes of elections for some time.

Calls for compromise

However, it is possible the government has calculated differently. They are aware of the damage a well-organised and well-funded Jamaat can do. The government is also confident it can tackle the violence with security measures.

And it is possible the BNP may even rein in its smaller coalition partner, and warn Jamaat not to rock the boat. The BNP senses it can win the next elections, if a level playing field is ensured.

The government accuses the BNP of carrying out its agitation as an effort to foil the war crimes trials. The BNP denies this and does not comment on the trials.

The US and countries in the European Union have called for a compromise so that an "inclusive election" can take place, and senior leaders from the two parties have agreed to talk.

Soon, they will have to address the critical question of an interim government that both could live with.

The government appears adamant to go ahead with elections on the scheduled date, but the negotiations suggest they may consider rescheduling the polls.

But the entire negotiating process, fragile as it is, could go completely off the rails if the protests over Mullah's hanging reach the intensity of February's unrest.

- Published12 December 2013

- Published8 December 2013

- Published26 November 2013

- Published4 December 2013

- Published25 November 2013

- Published4 September 2016