2014 - A year to fight the fear in Afghanistan

- Published

As the new year dawns, there has been a defiant crescendo of positive thinking from Afghan youth

2014 has at last arrived and for Afghans it's more than just another year.

A decisive political moment in their tortuous history is being called everything from a phobia to a syndrome.

But no sooner had the clock struck midnight than the fight-back began, with a volley of hashtags on social media.

#Afgwillliveon, #Who'safraidof2014? were some of the rallying cries in cyberspace to reject a negative narrative, lest it become self-fulfilling.

"Let's celebrate 2014 with a spirit of #Nofear #Nophobia," wrote Borhan Osman of the Afghanistan Analysts Network on Twitter.

Even in a country where every year has been called "critical," this one matters. Most foreign troops will pull out in 2014.

And presidential elections are meant to usher in a peaceful transition from Hamid Karzai to an elected successor, in a country where power has long been measured on the battlefield, not ballots.

Think positive

These first salvos of the year were fired by young educated Afghans who've come of age since the momentous events of 2001 which ended one of the darkest periods of Afghan history under harsh Taliban rule.

I asked one of the Afghans who joined this hashtag chorus to explain this defiant crescendo.

"I believe Afghans have been bombarded with panic and messages of uncertainty by media during the last 12 months," replied physician Fazel Fazly in a reference to grim forecasts of civil war, financial failure, and rigged elections.

As Nato troops prepare for a full withdrawal, there are still grave concerns about security

"I'm a medic so my humour is medically oriented, so I call it 2014 Syndrome," he pointed out, before adding a more serious note: "Afghans can't handle widespread negativism and this can directly affect realities on the ground."

Afghanistan has long been a country where perceptions of a situation can matter almost as much as realities on the ground.

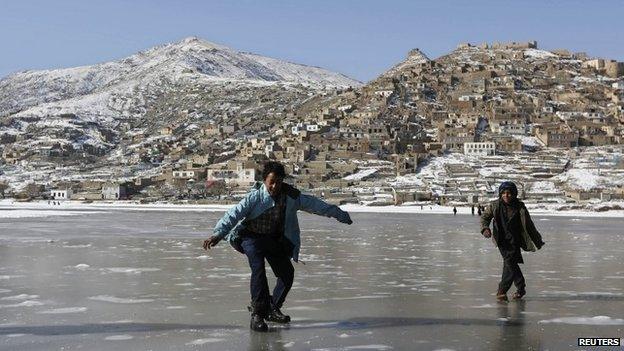

There's an echo of the anxiety that rippled through Kabul in the harsh winter of 1989 as Soviet troops prepared to pull out after 10 long years of war.

In a capital wrapped in a blanket of snow and a swirl of rumours, there were whispered conversations about whether mujahadeen fighters in the hills around Kabul would march in once the Red Army left. Outside Afghanistan, many predicted the imminent collapse of President Najibullah's order.

As a foreigner who stayed on in Kabul after Western embassies pulled out, I kept being asked by Afghans, with palpable nervousness: "What do you think will happen?"

Gloom magnified

Collapse only came a few years later, when Moscow drew down much of its financial and political support to its allies in Kabul.

Afghanistan is a very different country now but it's still rattled by pessimistic predictions, especially since they're now magnified beyond compare by social media and the unprecedented reach of televisions and telephones.

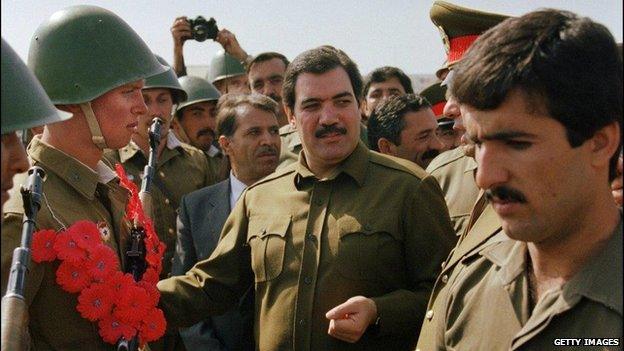

President Najibullah's (centre) order lasted for some years after the Soviet withdrawal

As 2013 ended, President Karzai's office was batting away yet another gloomy prognosis.

The latest has come from the US National Intelligence Estimate which predicted Afghanistan would descend into chaos if Kabul fails to sign a Bilateral Security Agreement with Washington, which would keep a contingent of US troops in the country after 2104.

"We strongly reject that (report) as baseless as they have in the past been proved inaccurate," asserted the President's spokesman Aimal Faizi.

Even the intelligence community is divided over how fragile gains made since 2001 are. But there's no denying that Afghanistan confronts monumental challenges this year on every front.

President Karzai's insistence on delaying his signature on a security pact, supported by many Afghans, has only added to this climate of uncertainty. But it also highlights the ambivalence that now marks the relationship between Afghans and their Western partners.

It's a country that still needs foreign aid and security assistance. But it also needs its own soldiers to stay at their posts, its politicians to put their country, not personal interests first, and needs a people to pull together.

#Glasshalffull

It is a country where about 70% of the population is under 25 - and many know this is the year Afghans will need to make a difference

There is real concern about aid levels, lucrative contracts, and investment plummeting as foreign troops leave. There is unease about widespread corruption. And the Taliban are still vowing to continue the fight.

Afghans have already lived through a Soviet invasion and pullout, mujahedeen infighting, strict Taliban rule, and an international engagement that helped develop their country in some areas, but disappointed in others. For many Afghans, it has always been a battle just to survive.

And that's just the last three decades.

No wonder some young educated Afghans, in a country where about 70% of the population is under the age of 25, are starting this year with hashtags like #glasshalffull.

They know this year is a year where Afghans themselves can make the difference.