Bangladesh's bitter election boycott

- Published

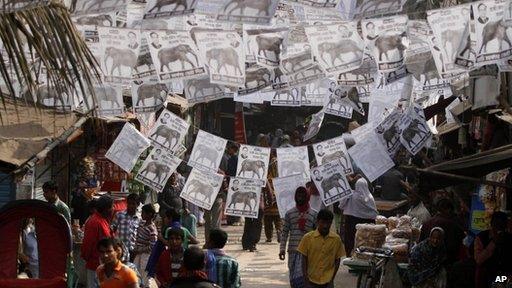

The opposition boycott has meant that election fever is absent from many parts of Bangladesh

As Bangladesh elects a new parliament on Sunday against a backdrop of increasing political violence, BBC Bengali editor Sabir Mustafa looks at why the main opposition party is boycotting the polls.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) says that it will not participate unless the vote is held under the auspices of a neutral government.

As a result, 153 of the 300 seats have already been "filled" because there is only one candidate. Polling will take place in the remaining 147 seats but in the absence of the main opposition parties, voters will have little real choice.

To outsiders, the argument over the use of a caretaker government may well seem a little arcane but parliamentary polls have been held in Bangladesh under neutral caretaker governments since 1991.

The caretaker system was abolished in 2010 by the governing Awami League, which used its two-thirds majority in parliament to force through the changes.

The government now remains in power and acts as "caretaker" once election schedules are declared. The BNP says this was done to enable the Awami League to rig the vote.

Massive losses

There has been a flurry of activity by Western envoys in Dhaka to break the deadlock.

The bitter animosity between BNP leader Khaleda Zia (left) and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is reflected among their supporters

A special envoy of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon came to Dhaka last month with the aim of getting the two sides to talk to each other but the dialogue never got off the ground.

The government has insisted that the BNP should take part in the polls within the existing constitutional framework. It says that the opposition should discuss any changes it wants after the vote.

The BNP and its allies - including the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami party - have been conducting a violent campaign of strikes and countrywide road and rail blockades.

The protests have left more than 100 people dead in recent weeks.

Scores of opposition supporters have died in police shootings and dozens of commuters have been burnt to death by protesters throwing petrol bombs at strike-defying buses.

The economy has suffered massive losses as a result of the unrest.

State of emergency?

Many people fear the military might intervene if law and order breaks down and the economy is threatened with total meltdown.

The opposition have been accused of setting fire to buses as part of their campaign against the vote

There are worries that the Awami League might impose a state of emergency after the elections to crush any opposition to the newly-elected government.

So in many ways the elections are more likely to be a case of constitutional box-ticking than a genuine choice for the public.

But the Awami League will nevertheless claim victory. While they may have acted constitutionally, it is arguable whether their actions are truly fostering democracy, especially when opinion polls suggest the BNP may win power if free and fair polls are held.

Not only do the polls have little credibility, but the public may also feel cheated. The big question on the morning of 6 January will not be who won but rather, what will happen next?

It is likely that India will press Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to engage in serious dialogue with the opposition to work out a new formula for election-time governments.

These talks would pave the way for the next elections well before they are nominally due in 2019. But again the big question is how soon?

Unease and tension

Ideally, most people would like to see the next vote take place no later than six months from now.

There is speculation that the government may impose a state of emergency after the vote

But the Awami League might have different ideas and stretch their period in power to a year or more.

In that event, we can expect more violence and instability.

The sense of tension has not in any way been alleviated by what may commentators have called the Jamaat factor.

The party has been waging a relentless campaign over the past couple of years to implement its agenda, often attacking and killing police officers.

All the top leaders of the Jamaat have been prosecuted for crimes against humanity committed during Bangladesh's war of independence in 1971.

Four have been sentenced to death and one was hanged last month.

Jamaat supporters feel that the Awami League, with Indian backing, is out to destroy them.

The Awami League on the other hand fears that if the BNP returns to power, Jamaat leaders will exact revenge and abolish the war crimes tribunal and have its verdicts overturned.

Awami League leaders are pressing for the BNP to delink itself from Jamaat and not take a position against the war crimes trials.

What the BNP does in relation to its alliance with Jamaat will significantly influence any dialogue with the Awami League over elections in the weeks ahead.

- Published26 November 2013

- Published26 December 2013

- Published28 October 2013

- Published10 March