Kyrgyzstan's dilemma over Russian-led customs union

- Published

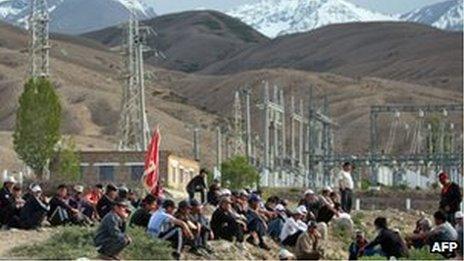

Some traders do not see the benefits of joining the Russian-led customs union

Kyrgyzstan wants to join the customs union led by Russia - although such a move carries risks. However unlike Ukraine, where there have been mass protests against closer ties with Russia, the Central Asia state has few other choices, reports the BBC's Abdujalil Abdurasulov in Bishkek.

Dordoi Bazaar in Kyrgyzstan is the biggest wholesale market in the whole of Central Asia. It is a city within a city. Endless rows of metal containers make it a bustling labyrinth where even locals may easily get lost.

The market prospers thanks to low customs tariffs with China. Kyrgyz traders import goods from Urumqi and Beijing and resell them to their wholesale customers from Russia, Kazakhstan and other neighbouring states.

Nearly a quarter of all Kyrgyzstan's imports come from China these days, according to the state customs service.

This sector thriving on cheap Chinese goods is in danger though - joining the Russian-led customs union will mean that all tariffs with non-member states, including China, will have to go up.

Considering that customs duties with China are 0% - or close to 0% - on many goods, the change is likely to be quite substantial.

"I don't think this is good for us," Irina, a shop owner in Dordoi says. "Our wholesale customers will stop coming here. People will have to close their shops, their containers."

Their main clients are from Russia and Kazakhstan and if these states have the same customs tariffs with China as Kyrgyzstan does, then their customers will have no reason to come to Dordoi, Irina says.

Clothing manufacturers may lose out if Kyrgyzstan does not join the union

At the moment, three states are members of the union: Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. The idea of the union is simple - to create a common market that will have no customs barriers.

In theory, membership of this organisation implies that Kyrgyz producers will have access to the vast markets of those three states.

However, there are certain risks for the Kyrgyz economy if it joins the union.

There are more than 100,000 people working in Dordoi alone, according to World Bank estimates. All these people may suffer from higher tariffs.

But the impact will be not just on traders. People who work in other industries dependent on Chinese imports may lose their jobs. Prices on about 500 goods, mostly consumer goods and food, are likely to go up. Poverty may rise.

But Economy Minister Temir Sariev says all negative effects of the membership will only be temporary and may last up to three years.

"If we adopt our legislation, if we change our economy's structure, then [with] perspective, the membership should be positive. Why? Because our main trading partners are Russia and Kazakhstan."

Indeed, a third of all imports come from Russia. Some goods are completely imported from the customs union states. Among them are oil products, wood, flour, coal and others.

"We are strongly integrated with each other," Mr Sariev says.

"And if we don't find the conditions for free trade with them, then in the future we may have serious obstacles in doing business."

Experts agree that refusing to join the customs union may also have a negative impact. Some industries, such as clothing manufacturers, may find themselves in a lose-lose situation.

"If we don't join the customs union, then they may increase customs duties [for our goods]," Farhad Tologonov from the Association of Light Industry said.

"And since this is our market and we export more than 90% of our products there, we will not win from that."

But at the same time, Mr Tologonov says clothing manufacturers will have to charge more for their products since they ultimately depend on textile materials and equipment imported from states outside the union.

As a result, they will not be able to compete with Russian producers and will have to give up their markets in Russia. And this industry contributes 7% of tax revenues, which impoverished Kyrgyzstan cannot afford to lose.

Transition period

The Kyrgyz government understands these risks and therefore is pushing for concessions when joining the customs union.

"We need a transitional period," Mr Sariev said. Within this period, tariffs will be raised gradually.

Kyrgyzstan is also asking to create a special fund to help its industries and people who lose their jobs. They also want the customs union states to assist in enhancing border facilities and have asked for Kyrgyzstan's major markets like Dordoi to be granted a free-trade-zone status.

At a meeting last December, however, the leaders of the customs union states said Kyrgyzstan would not get any concessions.

If they do not agree to Kyrgyzstan's conditions, "it won't be a catastrophe", Mr Sariev said.

Since Kazakhstan is planning to join the World Trade Organization and Russia - like Kyrgyzstan - is already a member, then, he says, the customs union states will "soften and reduce their tariffs".

However, not only is the business community in Kyrgyzstan concerned about higher customs duties, but they say non-tariff barriers may seriously hinder trade too.

"The customs union demands [that we] change our legislation, to [be party to] some agreements and protocols," said Azamat Akeleyev, a business analyst.

"Overall, the rules are harsher in the customs union, including technical, sanitary, veterinary and other regulations. In some cases, they make things more [organised], but in other cases, these are just harsher, less liberal rules that may stifle the growth of business."

Besides, Kyrgyzstan will have to open new laboratories and all goods will have to undergo a number of tests to meet the standards of the union. This could be too costly for most businesses.

Russian dependency

Observers are also worried that Kyrgyzstan will become even more dependent on Russia.

Esen Jumanov, director of the Bishkek Business Club, says there are certain sectors like the energy sector that "Russia could use to put pressure on Kyrgyzstan and [secure] a certain decision".

And once Kyrgyzstan is in the customs union, those pressures will only get stronger, Mr Jumanov claims.

So, if in the future Russia has a dispute with Ukraine and bans its confectioners as it did in the past, then Kyrgyzstan will feel obliged to follow the same policy.

Medet Tiulegenov, a political analyst from the American University of Central Asia, argues that economically Kyrgyzstan is not interesting for Russia.

Its membership of the organisation is more about increasing Moscow's influence in the region and projecting an image for its "internal audience that Russia is regaining its strength and [power] as it had before".

But Mr Sariev denies that Russia is putting any pressure on Kyrgyzstan: "We are a sovereign state and we will conduct our policies on the basis of our interests."

In the end, Kyrgyzstan has few choices.

Unlike Ukraine, where talk of getting closer to Russia has fuelled mass protests, Kyrgyzstan does not have the option of joining the European Union.

And turning away from Russia will have consequences that may be equally as painful as joining the customs union.

- Published7 November 2013

- Published1 June 2013

- Published31 May 2013

- Published24 February 2015