No grand bargain amid Thailand political crisis

- Published

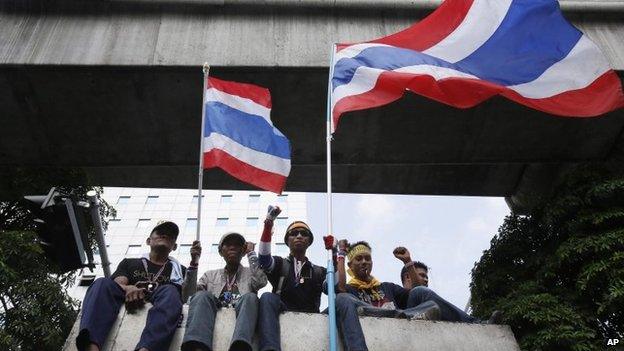

The anti-government protesters have been conducting their campaign since November 2013

The 2 February general election passed without serious violence; most of the valid votes cast were almost certainly for the governing Pheu Thai party. That was the good news for the government.

The bad news was that the election was sufficiently disrupted to end with a lower-than-usual turnout, and millions of voters blocked from voting by the anti-government PDRC movement.

These elections will have to be run again to fill the minimum of 95% of seats in parliament required by the constitution before a new government can be formed. That includes polling stations where advanced voting was obstructed on 26 January, and the 28 constituencies where protesters blocked any candidates from registering. The re-runs could take many weeks, and will surely be obstructed again.

It is a finishing line Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra's party is battling to cross, with her opponents determined to stop her; a war of attrition being waged on several fronts.

'No legal grounds'

The most visible front is the courts. Both the Pheu Thai party and the opposition Democrats have petitioned the Constitutional Court to have the other dissolved, something the court has done twice in recent years to previous incarnations of Pheu Thai. The court has rejected both petitions.

More seriously, the Democrats have also petitioned the court to annul the entire election, on the grounds that it was not held on one day, and that it violates section 68 of the constitution.

Legally, it is difficult to understand this argument. The election could not be held on one day largely because of the actions of a protest movement to which the Democrat party gives thinly-disguised support.

The use of section 68 is even more baffling. This section outlaws any actions that could threaten the existing democratic system, with the King as head of state. The Democrat argument appears to be that in calling the election at a time of turmoil, and against the advice of the Election Commission, the government put the political system in jeopardy.

"The constitution gives a clear and flexible mechanism to re-run the election where it has been obstructed," says lawyer Verapat Pariyawong. "It is ironic that the Democrats are citing section 68, as this really ought to be used to deal with the disruptions of the protesters rather than the actions of the government. There are no legal grounds I can see for annulling the election."

Democrat leaders, though, have expressed confidence that this petition will succeed. The Constitutional Court has a track record of rulings unfavourable to the Pheu Thai party. In 2006 it annulled another election boycotted by the Democrats, partly on the grounds that some of the voting booths were placed at the wrong angle.

The government has fought back with its own legal actions. It has obtained arrest warrants for 19 of the PDRC leaders, and says it will act on them, although remains wary of approaching protest leader Suthep Thuagsuban, who has former military special forces guarding him.

The protesters have blocked key road junctions and marched on government offices

There are also two ongoing investigations by the National Anti-Corruption Commission, one of Prime Minister Yingluck over her role in the controversial rice purchase scheme, and another of 223 Pheu Thai MPs over last year's attempt to amend the constitution. If the commission finds against her she would face impeachment in the Senate, although government officials stress this would not stop the cabinet from continuing to govern in its caretaker role.

The other arena this contest is being fought in is public opinion. Both sides have tried to take comfort from the election.

The PDRC and the Democrats point to the lower turnout in the election, even in pro-government strongholds, and the very low turnout in Bangkok, along with a high percentage of spoiled and "no" votes. They have celebrated the support their protest is getting from disaffected farmers who have not yet been paid for their last rice crop.

The government retorts that the number of demonstrators is dwindling, and that protesting farmers largely come from pro-opposition areas of Thailand. It attributes low election turnout to disruption, intimidation and the fact that many candidates in its own strongholds were running unopposed.

'Better than killing'

So what will the outcome of this battle be?

The opposition believes the government has been crippled by the protests, and will have to make a deal, addressing their demand for wholesale reform of the political system to start before an elected government is allowed to take office again. Key to this deal, they say, is the approval of Thaksin Shinawatra, the prime minister's brother, who is living in self-imposed exile in Dubai. Its precondition is that Ms Yingluck must step down.

PM Yingluck Shinawatra leads a government that won elections in July 2011

The government believes it will eventually reach the finishing line, although it is concerned about the impact on the economy if this takes too long.

Even if the Constitutional Court annuls the election, say its legal advisors, it would have to re-schedule another one within 60 days, which the Pheu Thai party is confident of winning again. "Even if it takes many months", said Deputy Prime Minister Niwatthamrung Boonsongpaisan, "that is better than us killing each other."

Pheu Thai officials say that even once they have formed a government, they accept it will be for a limited term, no more than one year, and that they must quickly establish a neutral reform body comprising representatives from all interest groups in Thailand, to reshape their political system.

The main problem with this plan is trust - the lack of it.

"I accept that a large amount of trust has been lost by us," said one minister. "We have certainly learned lessons from our last term of office. But would you trust Suthep with reform?"

From the now-shrunken areas of Bangkok he occupies with his followers, Suthep Thuagsuban still berates the Shinawatra family, promising the faithful that he will hound them out of the country.

If there is a deal, a grand bargain, on the horizon, to end Thailand's crisis, it is not visible yet.

- Published1 February 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published2 February 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published6 February 2014