Genghis Khan: Good weather 'helped him to conquer'

- Published

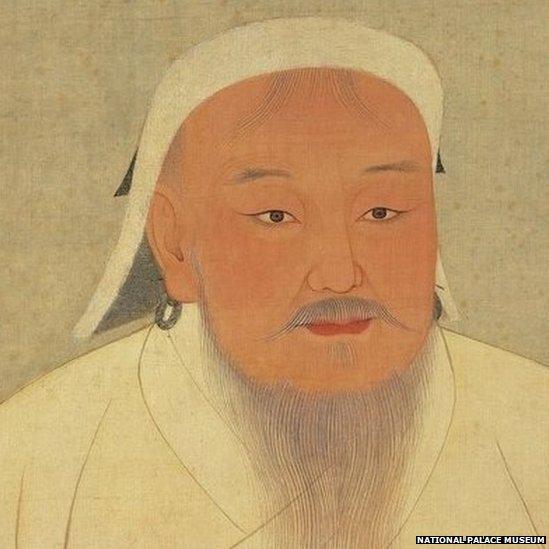

Genghis Khan was the founder of the Mongol empire, which historians say was the largest contiguous empire in history

The rise of Genghis Khan and the huge Mongol Empire in the early 13th Century may have been helped by good weather, scientists suggest.

American researchers studying the rings of ancient trees in central Mongolia have discovered that his rise coincided with the mildest, wettest weather in more than 1,000 years.

Grass grew at a rapid rate, providing fodder for his war horses.

Genghis Khan united the Mongol tribes to invade and rule a vast area.

It covered modern-day Korea, China, Russia, eastern Europe, India and south-east Asia.

Charismatic leader

The research shows that the years before Genghis Khan's rule were characterised by severe drought from 1180 to 1190, the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external said.

Present-day Mongolians regard Genghis Khan as the founding father of their country

But as the empire expanded from from 1211 to 1225, Mongolia saw an unusual spell of regular rainfall and mild temperatures.

"The transition from extreme drought to extreme moisture right then strongly suggests that climate played a role in human events," study co-author and West Virginia University tree-ring scientist Amy Hessl told the AFP news agency.

"It wasn't the only thing, but it must have created the ideal conditions for a charismatic leader to emerge out of the chaos, develop an army and concentrate power.

"Where it's arid, unusual moisture creates unusual plant productivity, and that translates into horsepower. Genghis was literally able to ride that wave."

Allied to the good weather, Genghis Khan was able to unite disparate tribes into an efficient military unit that rapidly conquered its neighbours.

For the oldest samples, Ms Hessl and lead author Neil Pederson, a tree-ring scientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, concentrated on an unusual group of stunted Siberian pines found while researching wildfires in Mongolia.

The trees were growing from cracks in an old solid-rock lava flow in the Khangai Mountains, according to a statement from Columbia.

Trees living in such conditions grow more slowly and are particularly sensitive to weather changes - and as a result provide an abundance of data to study, scientists say.

Some of the trees had lived for more than 1,100 years. the experts say, and one piece of wood they found had rings going back to about 650 BC.

- Published20 October 2013

- Published9 October 2012

- Published14 April 2012

- Published25 March 2011