Thailand to lift emergency rule as protests ease

- Published

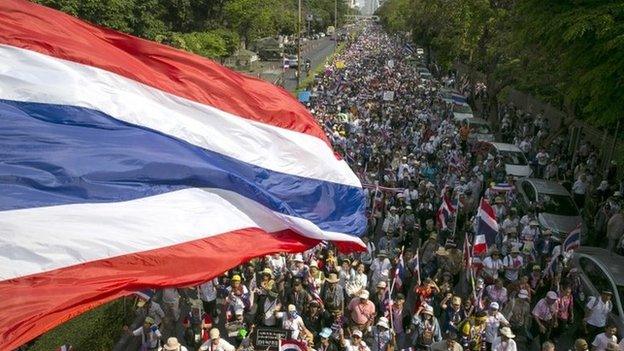

Anti-government protesters want Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra to step down

Thailand is to lift its state of emergency on Wednesday, as tensions ease following weeks of anti-government protests.

Officials say the emergency decree will be replaced by the Internal Security Act.

The 60-day emergency decree, imposed on 22 January in Bangkok and surrounding provinces, gave the government wide-ranging powers to deal with disorder.

Anti-government protesters want PM Yingluck Shinawatra to resign.

The protesters, who began their campaign in November, accuse the government of being run by ousted former leader Thaksin Shinawatra, Ms Yingluck's brother.

They want her government replaced with an unelected "people's council".

At the height of the demonstrations, protesters shut down key road junctions in Bangkok and blockaded government ministries.

Numbers have fallen in recent weeks, however, and the protesters are now mainly occupying a city-centre park.

At least 23 people have died and hundreds have been injured since the protests - Thailand's worst political violence since 2010 - began late last year.

Incomplete poll

Ms Yingluck approved the decision to lift the emergency decree during a cabinet meeting on Tuesday.

"We have agreed to lift the state of emergency and use the Internal Security Act (ISA) starting from tomorrow until 30 April as the number of protesters has dwindled... and after pleas from the business community," National Security Chief Paradorn Pattanathabutr told Reuters news agency.

The ISA, though less wide-ranging than an emergency decree, allows the government to impose curfews, put up security checkpoints and restrict protesters when the need arises.

The protests shut down parts of the capital, Bangkok, including major roads

The government declared the state of emergency ahead of the snap general election held on 2 February, called by Ms Yingluck in response to the protests.

But without the backing of the army, which is meant to play a central role in enforcing the state of emergency, it was ineffective, says the BBC's Jonathan Head in Bangkok.

Political violence continued and the protesters were able to block the election sufficiently to ensure that its results are still inconclusive, our correspondent adds.

The opposition boycotted the election, but polls proceeded as scheduled in most parts of the country. However, protesters disrupted voting in some constituencies, leaving parliament without a quorum, meaning a new government cannot be formed.

Despite the easing of protests, the political tensions remain unresolved. Ms Yingluck's government still has to navigate several legal challenges in the courts.

The Election Commission is still refusing the government's request to finish the polling.

The prime minister herself is facing charges of negligence over a government rice subsidy scheme, which critics say was rife with corruption. The scheme benefited farmers, who form the core supporters of the ruling party.

If found guilty, Ms Yingluck could be removed from office and face a five-year ban from politics.

- Published7 March 2014

- Published6 February 2014

- Published2 March 2014

- Published22 May 2014