Three surprises from a visit to Kashmir

- Published

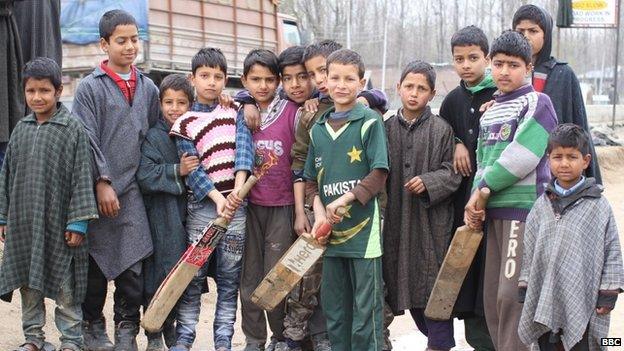

After years of conflict what do these young Kashmiris face in the future?

Anyone who has visited Pakistan will have consumed more than their fair share of news - or perhaps propaganda - about Kashmir. And after 15 years of travel to the country I know the Pakistani version of the Kashmir story backwards.

But now, after my first trip to the Indian side of the Line of Control, I have had the chance to reach my own conclusions about what's going on in Indian-administered Kashmir.

For the uninitiated, a brief history. When the British left the subcontinent in 1947 the status of Kashmir was unresolved. To cut a very long and contested story short, the Hindu Maharaja or King of Kashmir decided his Muslim majority state would join up not with Pakistan but India. The dispute has led to wars and today Pakistan has around one-third of Kashmir and India two-thirds, including the Muslim majority, and intensely politicised, Kashmir Valley.

Time has not healed the wounds. To keep control India has to deploy as many as 400,000 security personnel. Although all the numbers relating to Kashmir are keenly disputed it is probably fair to say that as many as 100,000 people have been killed in the struggle between Kashmiris and the Indian state.

That's the history - what's happening today? If you listen to the Pakistani version then India is repressing the aspirations of the Kashmiri people to join Pakistan or perhaps become independent. If you listen to India, it is defending its territory against jihadi militants sent over the Line of Control by a malevolent Pakistani security apparatus.

Everyday life in Kashmir differs greatly from what the average tourist sees

I arrived in Kashmir with a planeload of Indian tourists. They see a beautiful place. Kashmiri businessmen give them a warm welcome. If they should stray beyond the tourist hotspots then the Indian soldiers on patrol are, for them, a reassuring presence. But for the most part their holidays are untouched by the political conflict. The only minor inconvenience they will experience is that many of their mobile phones don't work in Kashmir. The Indian state wants to know exactly what people in Kashmir are saying.

Which is one reason why the Kashmiri perspective on life in Kashmir is quite different to that of the tourists. Kashmiris have learnt to live with both political violence and the Indian intelligence agencies. If you are talking politics in a café in Srinagar and a stranger sits at the next table - you stop talking. If a foreign journalist asks you how many people in the Kashmir Valley support union with Pakistan, off the record you say 25% but on the record you adjust the number down to 10%.

The Indian army has been in Kashmir so long, and it has been given such huge resources, that it now has a very tight grip on Kashmiri society. The militants - rumour has it there now just around 100 in the Kashmir Valley - are up against an army that not only monitors all communications but also has a well-developed network of paid informers and that has got to know every nook and cranny of Kashmir.

Kashmir Valley still sees clashes between the Indian army and militants, but violence has fallen

So what has surprised me about Indian-administered Kashmir? Three things.

First I had no idea how sharply reduced the insurgency is. For more than 20 years - as Pakistani TV showed at great length - there was intense violent conflict between separatists and the Indian army. There are still clashes today but so few that it is now possible to walk through Srinagar after sunset in relative safety. There are now more checkpoints in Peshawar or even Islamabad than in Srinagar

Secondly, the Indian state has been remarkably unsuccessful in winning over the residents of the Kashmir Valley. Even the pro-India National Conference seems to accept Indian a rule as an unavoidable reality rather than a desired outcome. Whether they come from political traditions that look to Delhi or to Islamabad there are very few residents of the Kashmir Valley who would not embrace independence with relief and enthusiasm.

Many students in Srinagar are adamant: Indian rule is oppressive and they are willing, if necessary, to live their whole lives in resistance.

Cricket is a popular sport passionately followed in Kashmir

And the third surprise? I have often read that Kashmir has an unusually tolerant political culture. Given the levels of violence and division it seems an implausible claim. But I have never been anywhere where people are so tolerant of each other's different political positions and religious beliefs. Just think of the genuine anger felt by liberals and conservatives about the relatively minor issues that define the political divide in the United States. Well in Kashmir you can hear a fairly hardline separatist describe the Indian army chief in Kashmir as a nice man.

Many Kashmiris disagree with each other. But for the most part they do so with grace and goodwill.

It's an approach that is, in part, a survival strategy. Everyone knows India is unlikely to make any compromises over Kashmir for the foreseeable future. While a post-imperial power such as the UK is willing to offer an independence referendum to the Scots, emerging powers don't give up territory. If there is the slightest chance that the Kashmiris would opt for independence, then they won't be given a vote on it.

When discussing Kashmir Western diplomats tend to raise their eyebrows and make some rather lame joke about how complicated it all is. I've always found it to be a highly irritating attitude. Kashmir remains one of the world's most intractable and important disputes which has blighted millions of lives.

And there's one thing about the dispute that didn't come as a surprise. There's no end in sight.

You can hear more from Owen Bennett-Jones on Newshour at 1300GMT on 2 April 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published10 March