Pakistan army eyes Taliban talks with unease

- Published

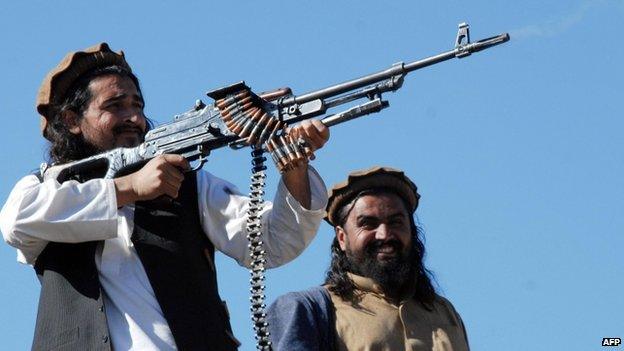

From the moment it was founded in 2007, the Pakistani Taliban have proved to be a formidable force.

Their suicide bombers have killed tens of thousands in cities and at the height of its power, in 2008, they controlled huge swathes of territory in the north-west and were even threatening the city of Peshawar.

"The government was in trouble. There were Taliban everywhere," says Gen Khalid Rabbani, who commands the 156,000 troops currently deployed to suppress the insurgency.

At one point the government even considered shifting the provincial administration in Peshawar to a safer place.

When jihadists took control of the Swat Valley and started beheading local opponents, the Taliban's advances made international headlines. The Taliban was just 100km (60 miles) from the capital Islamabad.

Then, after long periods of hesitation and attempted ceasefires, the army eventually took decisive action. In 2009, it evicted the Taliban from Swat and restored the writ of the state there.

The Pakistani Taliban continues to control North Waziristan

It was the start of a long, bloody campaign that has so far cost the lives of more than 5,000 Pakistani soldiers. Today, the Taliban has been pushed back to the point that it has control of just one tribal area - North Waziristan, and part of another, Khyber.

But the Pakistani Taliban remains a formidable force. It has an estimated 25,000 fighters and can still mount attacks and conduct assassinations in Pakistan's major cities.

'Safe haven'

The question of why the army has failed to mount an offensive in the remaining redoubt of North Waziristan is highly controversial.

Critics of the army believe that it is trying to protect Afghan Taliban fighters who use North Waziristan as a sanctuary. The Pakistani security establishment sees the Afghan Taliban as a strategic asset that can counter growing Indian influence in Afghanistan.

The high levels of distrust between the governments in Kabul and Islamabad have resulted in the Pakistani Taliban leadership sheltering in Afghanistan while the Afghan Taliban leadership shelters in Pakistan.

april2014.jpg)

Troops are stationed at Chagmalai Fort in South Waziristan

While the militants can move freely across the border between the two countries, the American, Afghan and Pakistani armies cannot. It is a situation the two Taliban movements have exploited to the full.

The army defends its failure to tackle North Waziristan on the grounds that it needs the government to provide political leadership and to carry public opinion by backing any military campaign.

But the government is pursuing a different track: rather than confronting the Taliban, it is engaging the militant movement in a dialogue process.

Possible split?

If the talks do not break down, there are two possible outcomes from the dialogue. The first is what the Taliban fear most - that some of the militants agree to stop fighting in return for prisoner releases and "compensation" by the government.

The army would then fight the remaining Taliban irreconcilables. The army hopes that, in those circumstances, the Pakistani public would support a military campaign against the Taliban groups that would have been seen to turn down a chance to reach a negotiated compromise.

Because of the rivalries within the Taliban movement the plan might work.

After the November 2013 death of the then Pakistani Taliban leader Hakimullah Mehsud in a drone strike, the organisation selected a jihadi from Swat, Maulana Fazlullah, as his successor.

The death of Taliban leader Hakimullah Mehsud (left) leaves open the possibility of the Mehsud tribe being split

It was the first time since its creation that the Pakistani Taliban was not being led by a member of the Mehsud tribe, and some Mehsuds are unhappy being under Fazlullah's leadership.

The government believes if it can split the Mehsuds the Taliban will be considerably weakened.

The second potential outcome of the talks is that the Taliban agree to stop sending suicide bombers to Pakistan's cites and in return the government allows the movement to conduct its activities in the tribal areas without state interference.

"The main [Taliban] demand is the restoration of the previous situation," says Major Amir, a former ISI intelligence officer and confidante of Nawaz Sharif, who is closely involved in the dialogue process.

Previously, he explains, the army was not present in the tribal areas and the Taliban might agree to a permanent ceasefire if the soldiers were withdrawn.

But having sacrificed so many lives fighting the Taliban, the army is in no mood to throw those gains away at the negotiating table.

"There can be just one deal: accept the constitution, accept the writ of the government and be a peaceful citizen. That is the deal," says General Nadeem Raza, General Officer Commanding in the South Waziristan tribal area.

'Jihad is over'

Over the last two years the army has undertaken a massive development programme in the tribal areas.

With US, Saudi and UAE money, army engineers have built roads, irrigation systems and electricity systems.

People in South Waziristan have been given new roads, irrigation and electricity systems

The effort has been so intensive that, in many respects, the tribal area of South Waziristan, generally perceived as backward and remote, now has better infrastructure than many other parts of Pakistan.

The army will be very reluctant to hand over all these improvements to the Taliban.

Rather, it hopes that the huge disruption caused by the fighting in recent years, which has forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes, will encourage a process whereby the traditional social structures in the tribal areas break down and the tribal people become better integrated into the rest of Pakistan.

But some supporters of the dialogue process believe the army itself is the cause of the problems and argue that the Taliban insurgency will soon fade away of its own accord.

"The army has no idea," says the opposition politician, Imran Khan. "The military is not a solution. Once the Americans leave the region, jihad is over."