How the Taliban groom child suicide bombers

- Published

Many of the children taken by the Taliban for indoctrination are young, homeless or in madrassas

On a cold winter's day, a stream of relatives, neighbours and well-wishers come to see 10-year-old Naqibullah at his uncle's mud house in Pakistan's Balochistan province. They are happy to see him alive.

Naqibullah had mysteriously disappeared from the madrassa in Balochistan where he had been studying.

There were five months of silence until one day a neighbour watching an Afghan TV station recognised Naqibullah in a police "line-up" of insurgents captured in the southern Afghan town of Kandahar.

"I ran and told Naqibullah's uncle that I just saw him on TV and that he had been arrested for trying to carry out a suicide attack in Kandahar," neighbour Abdul Ahad said.

Naqibullah's story is an unsettling insight into how the Taliban and other militants groom child suicide bombers.

Identify the vulnerable

Afghans have a proud warrior tradition, but suicide attacks were never a part of it. They emerged as a regular deadly reality of Afghan life in 2005 - a tactic adopted from Iraq's theatre or war.

And children have suffered disproportionately in the Afghan conflict, where government and international forces have been fighting the Taliban since it was toppled in 2001.

An Afghan Army soldier in an IED defusing exercise, but they can be caught unawares by children who blow them up

Children have long been deployed for insurgent activities such as blowing up IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices), surveillance and information about the whereabouts and location of Afghan and Nato security forces and government officials.

Teenagers have been found dragging away wounded Taliban, collecting dropped weapons and even fighting. Afghan authorities say they have arrested up to 250 children over the past 10 years for such activities.

The disturbing regional twist is the increasing number of child suicide bombers. Children are recruited simply for being children.

The capacity of Afghan security forces has increased and adult suicide bombers find it increasingly difficult to hit their target. Children are seen as more "recruitable" - easily influenced to carry out an attack and rarely suspected by security forces.

Madrassas as recruiting grounds

Just like hundreds of thousands of other boys, Naqibullah's uncle - who cared for him since the death of his father - enrolled him into a religious school. Poor families in Pakistan and Afghanistan send their sons to such madrassas for free education and lodging.

Children have suffered disproportionately in Afghanistan's conflict

Such madrassas are prime recruiting ground for Taliban groomers. Interviews with detained children reveal they are picked up from the streets as well and from low-income neighbourhoods.

In many cases, parents and guardians say they are totally unaware.

Girl recruits

There are extremely rare cases of girls being recruited.

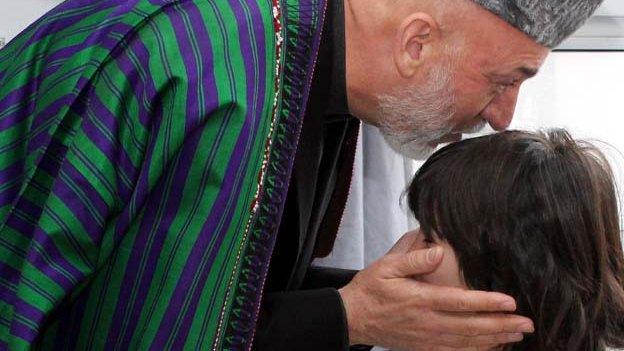

10-year-old Spozhmai got international media attention earlier this year after she was detained at a checkpoint

One 10-year-old girl, Spozhmai, got international media attention when she was detained on 6 January 2014 in southern Helmand province. She said her brother tried to make her blow herself up at a police checkpoint.

In 2011, an eight-year-old girl was killed in central Uruzgan province when she carried remotely controlled explosives to a police checkpoint in a cloth bag.

Pakistan the training ground

Pakistan is where many "recruits" are brainwashed and coerced into suicide bombing missions

More than 90% of juvenile would-be suicide bombers who have been arrested are "trained, lied to, and brainwashed or coerced in Pakistan", Afghan officials say.

But there is also evidence of training in Taliban-controlled parts of Afghanistan.

Last year, a father in Afghanistan's northern city of Kunduz handed over his teenage son to police.

"I did so because I feared [he] might have been radicalised when he disappeared for a few months," said the 50-year old man. His family had returned from Pakistan a year earlier.

Some have successfully carried out suicide attacks in Pakistan. One 12-year-old boy wearing a school uniform blew himself up killing around 30 in the town of Mardan in February 2011.

Promise of brighter future

Naqibullah says his handlers told him he would go to heaven and all his problems will end. Officials say children are offered a path out the boredom and drudgery of poverty by preachers with promises.

"They offer them visions of paradise, where rivers of milk and honey flowed, in exchange for giving up his life by becoming a suicide bomber," one official said.

Although confessions obtained from juveniles can sometimes be unreliable, they provide chilling accounts of how they were persuaded.

They are told that Afghan girls and women are raped by "invading foreign forces" and that the Koran is being burned by Americans

The children are told that it is their religious duty to resist the "infidel" coalition forces and that they and their parents will go to paradise

They are told that the Afghans they intend to kill "deserve to die" because "they are not true Muslims", or are "American collaborators"

Nevertheless, children are rarely told who their specific target is and why they deserve to die.

In some cases, they are simply lied to. Some were given an amulet containing Koranic verses and told it would help them survive. Some handlers gave children keys to hang round their necks and were told the gates of paradise will open for them

Taliban denials

There are of course international laws against the use of children in conflict.

Children are among the main victims of the conflict in Afghanistan

According to the Article 1 of the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, everyone under 18 is a child. Afghan law also forbids the recruitment of minors into armed forces or the police.

Taliban spokesmen usually deny using children, especially girls. Indeed all the three Laihas [Codes of Conduct and Regulations] issued after the fall of the Taliban regime in late 2001 prohibit youths with no beard to join their ranks.

But one Taliban official acknowledged that there may be violations by local commanders acting alone. For many the exact age is not important. Anyone beyond puberty and mentally sound is considered fit for fighting.

Rehabilitating children

According to Afghan security officials, more than 30 children accused of having links with the insurgency are still held at detention facilities.

Rehabilitation is complicated with scant resources. While some children go through rehabilitation steadily enough, according to one insider, a few even regret failing to carry out suicide missions.

Naqibullah describes what happened to him: "They kept me in the other madrassa for a few months. Then other men came and took me to Kandahar.

"One day they took me in a car, gave me a heavy vest to wear and pointed to [some] soldiers."

But the police stopped him before he exploded his vest and his handlers who were looking on from a distance left in the car.

To secure his release his uncle contacted local tribal elders, religious scholars and lobbied Afghan officials.

Back at his home the boy tells every well-wisher how happy he is to have returned.

- Published25 June 2013

.jpg)

- Published13 January 2014

- Published13 January 2014