Why do families kill their daughters?

- Published

Human rights activists protest against the killing of pregnant woman Farzana Parveen in the city of Lahore, Pakistan

The stoning to death of a pregnant Pakistani woman by her own family has thrust the issue of so-called honour killings into the spotlight.

What is an 'honour killing'?

It is the killing of a member of a family who is perceived to have brought dishonour upon relatives.

Video showed the women and men singing and dancing at a wedding, as Orla Guerin reported in 2012

Pressure group Human Rights Watch says the most common reasons are that the victim:

refused to enter into an arranged marriage

was the victim of a sexual assault or rape

had sexual relations outside marriage, even if only alleged

But killings can be carried out for more trivial reasons, like dressing in a way deemed inappropriate or displaying behaviour seen as disobedient.

"The perpetrator seeks to excuse it as some sort of protection of their family's honour, reputation or values," says Mustafa Qadri, Pakistan researcher for Amnesty International.

Last year, three women were killed in Pakistan after being captured on video "smiling and laughing in the rain outside their family home".

Men may also be targeted, by members of the family of a woman with whom they are perceived to have had an inappropriate relationship.

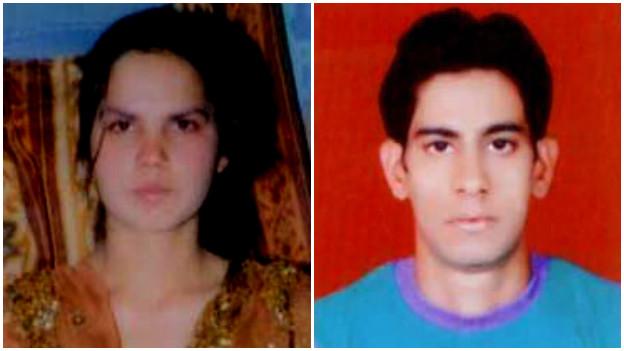

Last year in India, a young couple were murdered in Haryan state because they planned to marry despite being from the same caste. Nidhi Barak, 20, was beaten to death and Dharmender Barak, 23, dismembered alive.

But Rothna Begum, researcher on the Middle East and North Africa for Human Rights Watch, says women bear the brunt of such punishments because they are more widely perceived as "keepers" of family or community honour.

How do families justify the murders?

The idea that a murder can be honourable is believed to come from tribal customs where an allegation against a woman can be enough to defile a family's reputation - the idea that "a life without honour is not worth living".

Perpetrators have sometimes tried to justify their actions on religious grounds - but none of the world's main religions condone honour-related crimes.

In some countries, these tribal customs have been codified into law, which may constitute legal grounds for killing a family member.

In Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas for example, "rivaj" - or tribal custom - is codified without being defined. This could be interpreted to provide a legal basis for a killing, says Mr Qadri.

Nidhi and Dharmender were murdered allegedly by Nidhi's family for planning to marry

The killings are also more prevalent in disenfranchised or remote communities.

A collective failure by the authorities to prosecute such crimes, and the tacit endorsement by local clerics, contribute to them being more accepted, says Mr Qadri.

But above all else, they are a feature of deeply patriarchal societies where there is a belief that a woman's actions reflect on the men around her, he adds.

How widespread are such murders?

The United Nations Population Fund estimates that 5,000 women globally are murdered in this way, external each year. Last year, 869 women were said to have been killed, external in Pakistan.

Killings have previously sparked protests in places like Pakistan

Women's advocacy groups suspect the global figure is likely to be closer to 20,000 victims per year - but Mr Qadri thinks the figure is probably hundreds of thousands.

Although prevalent in the Middle East and Asia, it is a widespread global phenomenon, he says.

The UN describes it as a "growing problem", and says estimates are difficult because killings are rarely reported to police, and families often "cover up" the crime, disguising it as an accident or suicide.

Shafilea Ahmed was killed in front of her other siblings by her parents when she was 17

In the UK, figures suggest about 12 such killings take place each year.

One recent high profile case was that of 17-year-old Shafilea Ahmed, whose parents were convicted of suffocating her with a plastic bag. Prosecutors said her parents believed she had brought dishonour on the family by wearing Western-style clothing and mixing with white friends.

How does a family decide to kill?

"In the name of preserving so-called family honour, women and girls are shot, stoned, burned, buried alive, strangled, smothered and knifed to death," said a statement from the UN on International Women's Day.

Sometimes killings happen spontaneously, but in other cases they may be formal and organised. A meeting may be held by male family members and senior women who decide if a woman should be killed, and work out the method.

In the latest widely-reported case, Farzana Parveen, who was three months pregnant, was pelted with bricks and bludgeoned by relatives furious because she married against their wishes.

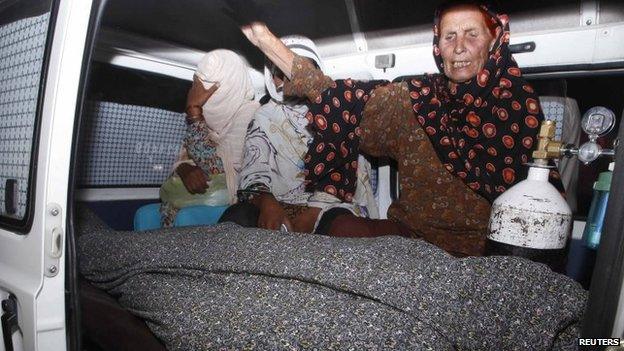

Women mourn over the body of Farzana Parveen

Are people ever convicted?

Most such killings are particularly difficult to prove or prosecute. There are often no witnesses and little motivation within the community for police to pursue suspects.

In Pakistan, conviction rates are very low because of blood-money laws which allow kin to forgive perpetrators, usually family members in such cases.

Even if convicted, men who have taken part may sometimes receive reduced sentences.

Rukhsana Bibi and her husband Mohammad Yunus were attacked last May

Rukhsana Bibi claims she survived an attempted an attack that left her husband dead in Kohistan, a remote and mountainous region in the northern part of Pakistan.

She is one of very few women who have spoken out to seek justice. No-one has been convicted of the attack.

"Honour killings" should be prosecuted as murder without exception, says Ms Begum.

Victims' families should receive protection and sentences should not be reduced where there are convictions citing violation of honour, she adds.