Afghan notebook: Second round lucky?

- Published

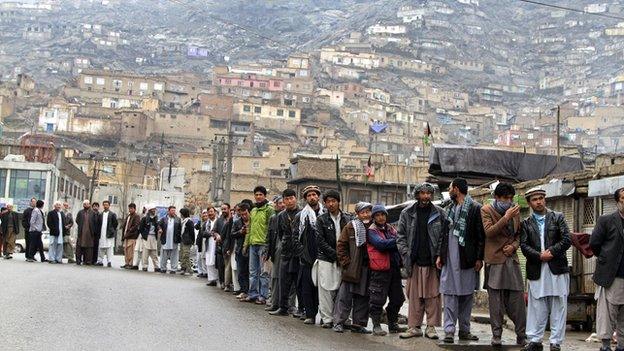

Afghan voters are preparing to queue again after turning out in large numbers during the first round

Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani are vying to replace Hamid Karzai in Afghanistan's presidential run-off on Saturday.

After the first round two months ago, thousands of election staff were dismissed over fraud allegations and there was widespread flooding in the north.

BBC Afghan reporters visited key parts of the country where the decisive second round will be fought out.

Herat - Harun Najafizada

In Herat 100,000 ballots were invalidated in the first round, but many were later allowed to stand

Voters in Herat told the BBC they were determined to vote in Saturday's run-off

Fraud allegations were widespread in the first round, but the western city of Herat stood out after the electoral authorities initially invalidated 100,000 votes.

At a local mosque used as a polling station in the Jebrael area on the east of the city, residents were still hotly debating what had gone wrong.

Mohmmad Ismail, an elderly man in a grey striped turban, said he felt sad that fraud seemed to be an inevitable part of elections in Afghanistan.

"At first I thought that I wouldn't vote again, but now I've decided that it's my responsibility," he told me. "I will go and vote a hundred times if need be, and the rest is up to the authorities."

At the busy bazaar outside Herat's historic Jami mosque, I found a similar mixture of disappointment and determination.

One women told me how enthusiastic everyone had been in the first round, and how upset she'd been to stand for hours in the rain to cast her vote, only for it to be invalidated later on.

Another man said he would be voting again but was hoping there would be far more transparency this time.

The head of the local electoral complaints commission, Abdullah Shirzai, defended his decision to flag up concerns about the validity of some of the votes.

It's really important for the overall electoral process to distinguish fraudulent votes from clean ones, he told me.

In the end the electoral authorities in Kabul overturned Mr Shirzai's decision and most of the invalidated votes were allowed after a recount.

Jowzjan province - Neda Kargar

Heavy floods in northern Afghanistan destroyed roads and houses and displaced thousands

Thousands of people lost homes and possessions, including their voting cards

The flash floods in April and May have caused massive damage here in Jowzjan.

At the height of the flooding tens of thousands of people were displaced, with homes and infrastructure destroyed.

And it's caused a whole new set of problems for the authorities responsible for organising the election.

In Khoja Doko district, I met some of the many flood victims still living in tents on bleak scrubland.

Conditions here are tough, but there's one thing that's particularly worrying people.

"We lost everything in the flood, including our voting cards," says 55-year old Noorullah. "I really want to vote, but there's no way I can."

Without his card, Noorullah and many others like him will not be eligible to vote again.

In our district alone more than 400 families were displaced and about 500 voting cards were lost," says Hamra, another local resident.

Hamra has asked the local election officials for help, but with no success.

Jowzjan electoral commission head Amanullah Faryabi, acknowledges that thousands of people have lost their cards. But he has no solutions.

"People want to vote," he told me. "But we can't help them as we don't have enough time."

Many people in Khoja Doko asked if I could help them get back their vote.

They all said they'd cast ballots in the first round. The fact they cannot do so this time, is clearly adding to their growing sense of isolation and despair.

"For the past two days we don't even have water here," says one mother, Gul Jan. "Our life here is very difficult."

Kandahar - Mamoon Durrani

.jpg)

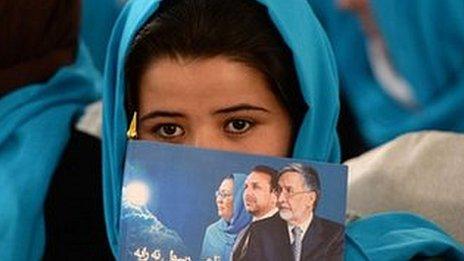

A supporter of Abdullah Abdullah at a campaign event in Kandahar

.jpg)

A campaign poster of Ashraf Ghani overlooks a security checkpoint in Kandahar

Kandahar is the one province which did not vote for either Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai or Abdullah Abdullah.

Former foreign minister Zalmay Rassoul came first here and both candidates in the run-off have campaigned hard to win over his supporters. The city is festooned with colourful campaign posters from both camps, and politics are a hot topic in tea houses, bazaars and mosques.

Afghan politics are closely interwoven with the politics of clans, influential elders and local power brokers. And both Dr Abdullah and Mr Ghani have wasted no time in underlining their local connections.

Abdullah Abdullah says his father is from Kandahar, while Ashraf Ghani says his mother is a Kandahari.

But in the first round there were signs that the power of the block vote, delivered by powerful tribal leaders and their followers, may not be as decisive as in the past.

Over the past two months there have been pledges of support for both candidates from different tribal leaders, civil society groups, academics and youth organisations.

Kandahar is traditional Pashtun heartland, but many people I spoke to now claim their vote will not automatically be decided by ethnicity or language.

Local teacher Feroz Mahbobi told me what counted were the candidates' integrity and capability. "Afghanistan needs decent and educated people more than ever before." he said.

So have traditional voting patterns changed?

It seems that influential clans in the province are themselves split and won't necessarily vote as one. New voters will also play a key role in deciding who wins here.

Young Kandaharis have been out on the streets in force in recent weeks organising rallies and waving banners in support of both candidates.

Talking to them, it's clear they're more likely than their parents to vote on an individual basis.

Predicting which of Kandahar's sons turns out to be the province's favourite is not easy.

BBC Afghan notebook

This is where our reporters share stories beyond the daily conflict and politics of a country going through the most important election in its recent history as foreign troops withdraw.

We'll focus on the surprising while treating the familiar from fresh angles, combined with a street-level view of a country in transition.

Most of the posts will be written, photographed or filmed by our journalists across Afghanistan.

You can use #BBCAfghanNotebook to follow our reports via Twitter.

- Published7 July 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published24 April 2014

- Published15 May 2014

- Published18 March 2014