Afghanistan elections: What's in a name?

- Published

As the people of Afghanistan prepare to vote in the presidential run-off, the BBC's David Loyn in Kabul ponders what the election says about the country.

You can tell a lot in South Asia from people's names. The two remaining names on the Afghan ballot this Saturday are laden with significance.

Number one will be displayed as Dr Abdullah Abdullah - the only candidate whose title is on the ballot.

In a country where even failed medical students are awarded the honorific Dr, a fully qualified eye doctor, as he is, wants everyone to know it.

But why are his first and last names the same?

Like many Afghans, he grew up with only one name, but when he first became prominent as a spokesman for the guerrilla leader Ahmed Shah Massoud in the mid-1990s, Western journalists insisted on a surname.

He replied that he had only one name, and said, slightly exasperated: "So it's Abdullah Abdullah if you like."

And it stuck.

But Abdullah was always more than a spokesman.

Pictures on the wall of his comfortable, but not grand house in the centre of Kabul, show him as part of the team close to Massoud - the only guerrilla fighter who managed to hold ground against the Taliban.

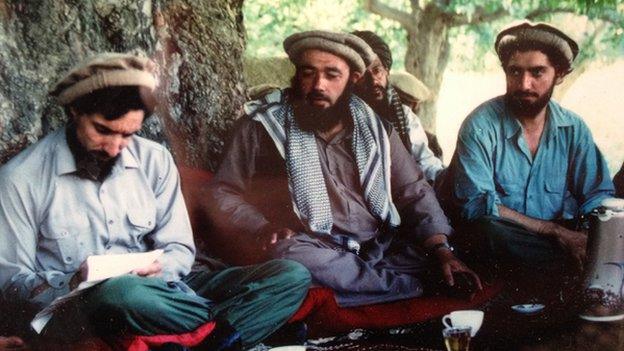

Abdullah Abdullah (far right) with Ahmed Shah Massoud, who was killed by al-Qaeda two days before 9/11

He worked as Massoud's envoy to allies across Afghanistan, and his fluent English made him the public face of the mujahideen movement to the outside world.

I first interviewed him in Kabul in 1996, shortly before the Taliban took the city.

Civil war had brought hunger and disorder, but Abdullah was urbane and well-turned out. He likes to wear cravats, and fine Italian shoes.

Allegations of affairs, including the pursuit of the daughter of an Afghan diplomat to France, have not damaged him.

And he has a keen interest in his country's history. Alongside the idealised portraits of Massoud in his house is a fine collection of British prints of Afghanistan from the 19th Century.

Number two on the ballot paper is Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai - and once again the way he presents his name is freighted with meaning.

As an economist with the World Bank, and author, he was plain Ashraf Ghani. The addition of Ahmadzai is a reminder to Afghan voters that he is a Pashtun elder.

Apart from a brief period after a rebellion in the late 1920s, Afghanistan has always been ruled by a Pashtun.

Afghanistan's largest ethnic group, although not a majority in the country, Pashtuns are prominent in the south and east.

Ghani (right) with Dostam on the campaign trail

During the time of British control in neighbouring India they were known as Pathans, and had a fearsome reputation. The Taliban were a Pashtun movement.

Ashraf Ghani's appeal is as an economic moderniser. He told me the economy is imploding, on track for zero growth this year.

He has acted as an adviser to many other failing poor states, and wants to bring that expertise to Afghanistan, although some Western diplomats privately express concern that while his ideas may look good on paper, he lacks practical political skills to deliver results.

He won a derisory number of votes in the 2009 election, coming fourth behind Hamid Karzai, Abdullah, and a populist anti-corruption agitator Ramzan Basherdost, external.

In order to avoid similar humiliation this year, Ashraf Ghani's most controversial move was to team up with General Abdul Rashid Dostum.

He once called the former warlord a "known killer", but secured an apology from Dostum for past mistakes in return for giving him a place on his ticket as vice presidential candidate.

There is no doubting Dostum's popularity among the Uzbek community in the north.

In election rallies I spoke to a number of people who were backing this campaign because Dostum was on it, not really knowing who Ghani was.

Abdullah Abdullah, seen here in Kandahar, was ahead in the first round

But Abdullah contemptuously says Ghani cannot bring Dostum to the south such is his unpopularity, and cannot even campaign with his portrait there.

In April, during the first round of voting, there was extraordinary euphoria in the streets and a very high turnout.

The Taliban were mostly kept at bay, although there were 300 serious attempts to disrupt the polls - more than twice as many as were reported at the time.

Few expect the turnout to be as high this weekend, which makes predicting the outcome difficult, although Dr Abdullah Abdullah was so far ahead in the first round, that it would be hard for Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai to catch up.

But the real significance of the names on the ballot paper is the one that is not there, Hamid Karzai, bowing to the new constitution that prevents him from standing again.

If it comes off, this will be the first peaceful transition of power here since 1901. For once the word historic is appropriate.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

- Published10 June 2014