Why is China's leader visiting Seoul?

- Published

.jpg)

The Chinese and South Korean leaders are set to get along well

Chinese President Xi Jinping is beginning a two-day visit to South Korea. It is the first time a Chinese leader has landed in Seoul before visiting North Korea, and the presidential summit is expected to focus on tackling Pyongyang's nuclear programme. But the regional perspectives from Seoul and Beijing are still very different.

Chinese presidents are, according to Mao Zedong, supposed to be as close as "lips and teeth" with their North Korean counterparts. Seen in those terms, today's picture looks a little skewed. Mr Xi's arrival in Seoul marks his first trip to the Korean peninsula as Chinese president - something of a snub to his ally in Pyongyang, or at least a rather pointed change in political tone.

China is playing down the significance of this timing. Mr Xi did visit Pyongyang as vice-president in 2008, before North Korea's current leader took office, and there are good reasons why North Korea's young and inexperienced ruler Kim Jong-un may not have wanted to leave his capital and pay homage in Beijing.

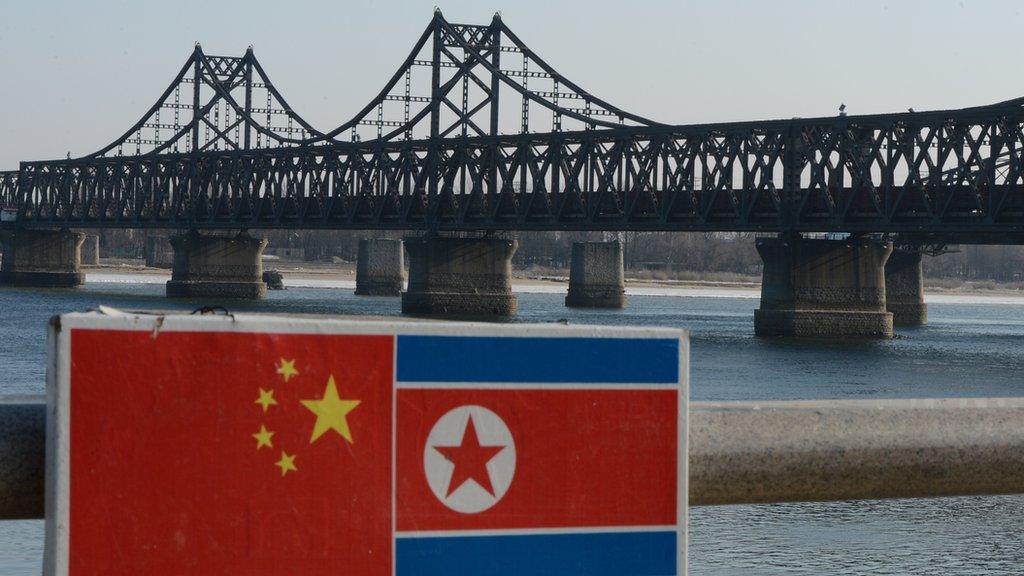

But there is little doubt that relations between Beijing and Pyongyang have seemed cooler in recent years. Since coming to power in 2011, Kim Jong-un has ignored the advice, gentle chiding and growing irritation of his economic and political benefactor, and pressed on with a long-range rocket launch and a nuclear test.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has not yet held a summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un

'Complex impact'

In contrast Mr Xi seems to have discovered a personal spark with South Korea's President Park Geun-hye.

The two leaders have met four times already, and Ms Park was received with great personal warmth during a state visit to Beijing last year. In return, she addressed a university audience in Chinese and has spoken about her admiration of ancient Chinese culture.

The two countries have also been growing much closer in economic terms: China is now South Korea's largest trading partner and both sides have been working towards a free trade agreement. Quite a rapid rise for countries that only established full diplomatic relations in 1992.

Public opinion has shifted markedly too. A recent poll carried out by the Asian Institute in Seoul suggested that almost two-thirds of the South Korean public now see China as a cooperative partner, with less than a third viewing it as a rival - and the number of people who said they thought China would take North Korea's side in another conflict has also dropped sharply, by more than half.

But beneath the surface, the picture is murkier. That same opinion poll found that a majority of South Koreans saw China's military rise as dangerous, either to their own nation or the region at large, and 71% thought China's growing economic power was a threat.

Professor John Delury, a Sinologist at Seoul's Yonsei University, says that China's approach to South Korea is strikingly different to its image elsewhere in the region.

"The narrative that China's being assertive and antagonising all its neighbours really doesn't work up here in North East Asia," he said.

"China's getting along quite well with South Korea and South Korea's much happier with Mr Xi in Beijing than Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. So it shows that China's rise is having a much more complex impact on the region than if you just look at the dispute with Vietnam and the Philippines."

Regional disputes still cloud relations between Asian neighbours

Both China and South Korea have expressed concern at Japan's changing military policy

China's ties with some South East Asia nations are strained over maritime territorial disputes

'Grand scheme'

Despite that new warmth and strategic interest, though, the two leaders' discussions today are likely to expose the old intractable differences at the heart of their political visions.

Both Mr Xi and Ms Park may agree that North Korea's nuclear programme is undesirable but they differ on how to stop it.

South Korea would like Beijing to do more to pressure Pyongyang, but for decades China has made the strategic calculation that stability in North Korea comes first - in its eyes, avoiding implosion of the regime is more important than avoiding nuclear tests.

Instead, Beijing has encouraged all parties to return to talks without pre-conditions. Seoul and Washington say that amounts to "buying the same horse twice". The discussions here will be watched for any small shifts in tone by Beijing, but the basic parameters of China's strategic interest are unlikely to change.

And there are those who say that China's interest is moving away from the North Korean issue anyway. Hwang Byung-tae, a former South Korean ambassador to China, believes that the two leaders might have very different ideas about what is important right now.

"South Korea is strategically important [to Beijing] because of China's relationships on its eastern boundary," he said.

"First there was America's pivot to Asia, then Japan's new nationalism, there's old rancour with Vietnam and territorial issues with the Philippines. South Korea lies in an important position geographically and friendly relations with it are part of China's grand scheme."

- Published12 April 2013

- Published5 April 2013

- Published13 February 2013

- Published10 August 2017