The Karzai years: From hope to recrimination

- Published

A look back at Hamid Karzai's time in office

It all began on 5 December 2001 - a grey winter's day in Afghanistan.

Far away, in the early hours at the grand Petersberg Palace in Bonn, Afghan delegates at a UN conference finally agreed that Hamid Karzai would be their new interim leader.

In Kabul, I heard the news on BBC World TV and immediately reached for our satellite phone.

"Hamid, what's your reaction to being chosen as the new leader?" I shouted down the crackling line when the former mujahedeen spokesman I had known for years answered his satellite phone at his makeshift military base in Kandahar in southern Afghanistan.

"Am I the new leader?" he replied, a note of anticipation rising in his voice.

Still dealing with the last remnants of Taliban resistance, Hamid Karzai had just survived an aerial attack by a stray US bomb that killed three US soldiers and many Afghan fighters.

He had not received the call from Bonn and he did not even mention the incident.

"Are you sure?" he queried.

I told him I had heard the news on the BBC.

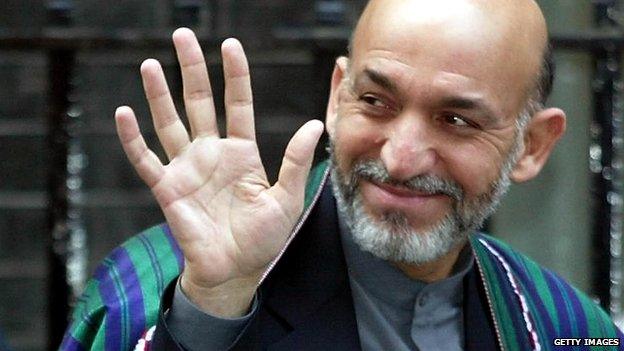

Over 13 years, Hamid Karzai has argued his case for Afghanistan with many world leaders

"That's nice," was his first, simple reaction in his signature, folksy style.

So began the Karzai years in power.

As they near their end, errant Nato attacks and a deeply strained relationship with his most important ally count as his "biggest disappointments".

"Do you remember that day nearly 13 years ago?" I ask him as we stand close to the arch of the Haram Sarai palace in the heart of the heavily fortified palace compound.

"We arrived at 04:00 and there was no electricity or heating," he recalls.

Hamid Karzai facts

Has led Afghanistan since US-led invasion toppled Taliban in 2001

Elected in 2004, re-elected amid vote fraud claims in 2009

Urbane, well-educated politician who was feted by foreign leaders at the outset

Relations with US and Nato have grown frayed in recent years on issues of corruption and civilian casualties

Third child, a daughter, was born in March

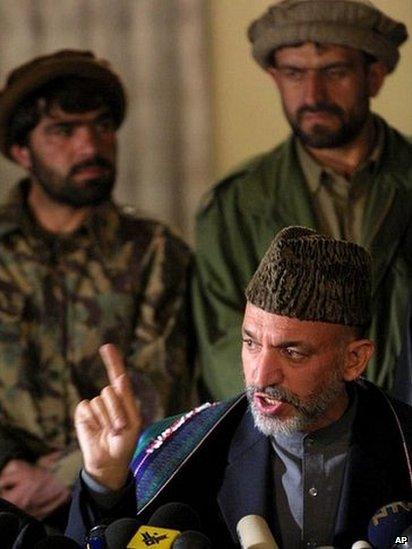

When Afghanistan's newly chosen leader made it to an expectant Kabul on 13 December - the day the first winter snowflakes fell - he told me: "The first priority is total peace and security for the people of Afghanistan."

Speaking inside a cold dark palace that day, surrounded by Afghan fighters and friends, he also spoke of other priorities including "an economic possibility so that our people earn a decent living... a fight against terrorism to finish it completely... to make Afghanistan a country ruled by law, ruled by regulations, that gets back its institutions".

Wearing the same kind of grey Karakul cap he still dons to this day, he spoke of how "good would come" if foreign troops were able to help Afghans, as they built their own security forces.

The newly-sworn in President Karzai embodied the world's hopes for a more stable, peaceful Afghanistan

Now, two smartly dressed sentries stand guard outside the Haram Sarai entrance, on the edge of manicured lawns fringed with roses in colourful bloom.

Afghanistan today is, undeniably, a different country.

But there is still no peace or prosperity for the vast majority of Afghans who had dared to hope that the end of Taliban rule would also finish three decades of punishing war.

In 2001, Hamid Karzai seemed to embody the hopes of an entire nation - a mujahid from the war against the Soviets who was not a warlord; a Pashtoon tribal leader who was an ardent nationalist; an English-speaking Afghan at ease in the West who kept the best of his country's traditions.

Much to the surprise of those who worried he was not up to this greatest of challenges, he strode confidently on to the world stage with charm, charisma and that distinctive green silk chapan.

But re-building a land shattered by poverty and war turned out to be much harder than anyone expected. A leader who lacked the resolve to face up to powerful warlords, and the resources to fight or negotiate with the Taliban on his own, grew ever more frustrated and angry.

After his narrow escape in a 2002 assassination attempt in Kandahar, which we witnessed at first hand, he has been forced to spend most of his time in his veritable fortress. But in conversation and speeches, he constantly invokes his meetings with Afghans from more ordinary walks of life, who come to see him or whom he meets on his rare forays beyond the walls.

"Do you feel you failed the Afghan people?" I ask the leader who was first selected in Bonn, confirmed by a traditional assembly or Loya Jirga, and then elected in two presidential polls.

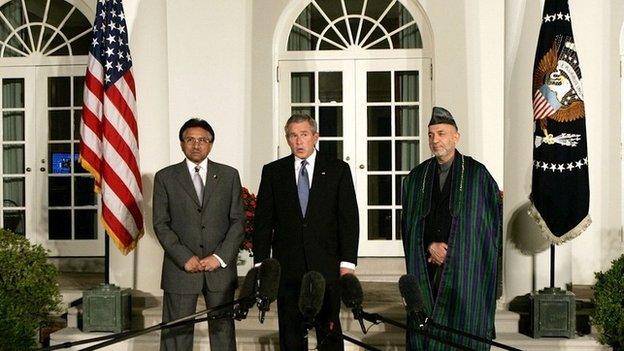

Hamid Karzai has had a complex relationship with both the United States and Pakistan

"Afghanistan is a much better country," he responds, without hesitation, as we sit in the elegant marbled hall that became his place of choice for formal interviews. As he prepares to leave office he agreed to sit down with me and my colleagues from the BBC's Persian and Pashto services.

"We still have problems, we are still a poor country, one of the poorest in the world. We have a long journey ahead of us as a nation."

He speaks with visible affection of a country that "became the home of all Afghans. We practised democracy, we voted, there's education, freedom of speech, of expression, and Afghanistan's flag is flying all over the world".

But then a 56-year-old leader with a trim grey beard and three young children expresses regret.

Lyse Doucet asked Hamid Karzai about his proudest moment as he prepares to step down

"There are many happy children, but sadly too many children that became sad, who lost their families."

For a man who promised his people peace, he says "lack of peace is a regret I will take with me".

"I wish there was not so much loss of life and the war on terrorism was fought genuinely in the right place."

A few years ago, in an outburst of private pain at a public gathering, he invoked his love for family and nation.

"For God's sake we must stop this violence," he implored the Afghan gathering as he wiped his tears to thunderous applause. "I fear my son Mirwais will have to leave this country. I want him to grow up here."

The Karzai Years

World News GMT times as follows:

Sat 12 Jul 12:30

Sun 13 Jul 00:30 , 07:30, 19:30

BBC News Channel (BST)

Sat 12 Jul 14:30

Sun 13 Jul 05:30, 10:30, 16:30

Mon 14 Jul 01:30

As foreign combat forces prepare to pull out at the end of 2014, Afghans grow increasingly worried about a declining economy, deteriorating security and the threat of a Taliban return.

But President Karzai remains stubbornly optimistic about his country and his people.

"The year 2014 turned into a devil for Afghanistan, an evil for Afghanistan, but it proved wrong," he said, summing up what has become known among Afghans as "2014 paranoia".

"We're moving forward, let me repeat myself, if it is Afghanistan alone, and its people, we will have no problem. If there is a broader international conspiracy for the region, then of course we will fall victim."

Now he sees conspiracies in many places.

Over nearly 13 years, over tea served in the palace's delicate china cups, I have heard the president's language about his Western allies evolve from special friends to "a business-like relationship" to "treacherous".

"Foreign forces have not brought any stability to Afghanistan and they will not," he now insists with a deeply felt sense of betrayal.

Casualties of the conflict have weighed heavily on President Karzai

"Yes, we do need international support where we don't have the means to sustain ourselves, that is welcome, we are grateful."

But when it comes to the "war on terrorism" he reiterates his often-repeated view that the "fight has to be genuine and true and that is not in the homes and villages. It has to go to the sanctuaries and training grounds and to the financial support to terrorists beyond Afghanistan".

It is a point Hamid Karzai has stressed since he came to power. Everything from satellite imagery to telephone intercepts back his view, and the view of many Afghans, that the root of the problem lies in sanctuaries of the Taliban and other armed groups in neighbouring Pakistan.

Western leaders, who had warmed immediately to a well-spoken Afghan with an infectious sense of humour, now speak with dismay about what they see as erratic behaviour verging on paranoia.

I point out that his Nato allies are astonished and angry when he accuses them of deliberating trying to create instability.

"The consequences are what we see," he explains. "Intention is a different issue, it's hidden from us.

"I see the results. The region is a lot more unstable, there is a lot more violence. I hope that can be reversed and I hope that I'm termed wrong one day by the West, by their good work to bring more stability."

The imbroglio over the 2009 presidential election also still festers like an open wound. Despite credible reports of significant fraud, he holds Washington's perceived desire to see him replaced entirely responsible for a crisis that led to a bitter standoff between him and his main challenger, Abdullah Abdullah.

"How can a nation which talks about promoting democracy do so much to destroy it?" he remarked in a conversation last year, pointing to comments from former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates who wrote how top US diplomats had tried to manipulate the election outcome "in a clumsy and failed putsch".

On 13 December 2001 Hamid Karzai spoke to Lyse Doucet about his hopes for Afghanistan

Even though the president's outlook is now clouded by seeing America's hand in every failure, there is always some evidence he can use to support what can often be extraordinary claims.

At his desk where he took some of the most difficult telephone calls with his allies including from Washington, I ask him when the conversations started changing from being very friendly to being, at times, barely on speaking terms.

He says the turning point was 2007 and the main issue was civilian casualties.

"But I never hung up the phone," he insists.

In recent years he has repeatedly railed against Nato attacks that mistakenly kill innocent Afghans.

His critics point out that he lashes out in that direction more often than he does against casualties from Taliban attacks even though UN figures make it clear the vast majority of deaths and injuries are caused by violence from insurgent groups.

And when it comes to the Taliban, President Karzai firmly rejects any suggestion that their brazen and brutal attacks confirm a rejection of peace talks.

"The Afghan Taliban are in contact with me every day with exchanges of letters, meetings, and a desire for peace," he insists, brushing aside their frequent statements that they will not talk to a leader they dismiss as an "American puppet".

Again he lays the blame for the failure of negotiations squarely at the door of Washington and Islamabad, not the Taliban.

And what about his own responsibility when it comes to another issue that troubles Afghans - the rampant corruption? Why did he look the other way and not hold his officials and allies to account?

Despite years of diplomacy and military operations, the Taliban continues to launch deadly attacks

"Hang on!" he declares. "Who brought the contracts? The Afghan government didn't give any contracts, the US did that.

"The layers of sub-contractors, the billions of dollars thrown in, who did that?" he demands.

A recent Pentagon report backs up his claim that far too much money flooded a fragile system unable to absorb and control it.

But last year's assessment from Transparency International, external ranks Afghanistan as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, just above North Korea and Somalia.

"I will take responsibility for the petty corruption in the day-to-day administration and delivery of services," the president concedes. "But the big money is not ours nor did we have control of it."

After nearly 13 long hard years, Hamid Karzai insists he is now ready to go, that it is time for a new leader to do "what is undone".

In 2001, he seemed to be the right man at the right time. For many Afghans, the challenges of 2014 need a new leader at the helm willing to confront the major problems and issues Hamid Karzai was unable or unwilling to resolve, including what many Afghans regard as a vital bilateral security agreement with the US.

We often called Hamid Karzai the "big tent" man.

He insisted everyone should have a place in the new Afghanistan, even the warlords who, repeated human rights reports said, should be tried for war crimes. He refused to allow the formation of political parties that would have helped Afghanistan move away from faction-based movements into a more mature political culture.

He always insisted there was no "opposition" in one big Afghan nation. Years ago, a frustrated UN envoy said Hamid Karzai should have been a "priest", not a politician.

His friends say he was like his father, Abdul Ahad Karzai, from whom he inherited the mantle of the Popalzai tribe when he was murdered. He did not like confronting people, and instead relied on his personal armoury of teasing, cajoling and bestowing rewards.

Over the years, Afghans looking for positions or permissions were infuriated by a leader who would make promises to one group in the evening, and a rival group in the morning.

Hamid Karzai wanted to be like a father of the nation who could heal his country's wounds and strengthen its institutions to allow it to stand on its own two feet.

He understood instinctively how power worked, through tribal and militia networks, right down to village level. An Afghan friend told me of his amazement when the president was able to name district chiefs from across the country.

But he never felt he had the power of his office.

As commander in chief, he was thwarted in the early years by having fewer men and less money than the powerful warlords. In later years, he was embarrassed and angered by well-resourced foreign armies who went into Afghan villages doling out money and conducting raids.

One US commander once told me that when he went to see the president to inform him that they would soon launch an offensive in Kandahar, the president replied that it was the first time he had been informed in advance.

The leader who famously never took holidays, save a few days walking in the hills of Scotland, now says he will take the shortest of breaks and then focus on many other projects, including writing. No-one doubts that in his newly-built house, on the edge of the palace, he will continue to play a role.

He describes himself as "more experienced, quite realistic, no more wishes or ideas about others that are not as I thought they were, and hardened".

As night falls, he resumes the routine he has kept almost every day since he entered the palace. He walks home inside ever-multiplying palace walls, flanked by aides and bodyguards who struggle to keep pace with his brisk stride. Two armoured vehicles bring up the rear of his procession.

Inside his own gate, he runs into the arms of his first daughter, three-year-old Malala, as his eldest son, eight-year-old Mirwais, cycles enthusiastically with his friends, weaving circles across sprawling lawns.

"Did you miss your Daddy?" he asks his pretty, doe-eyed daughter as he hugs her close. "Let's go then."

Post-war Afghanistan

$60bn

in civilian aid 2002 - 2012

35.8% below poverty line

-

8.6m children in school

- $20.7bn GDP - up from $5.3bn in 2004

-

17,605 civilians killed since 2008