Eagle-eyed Indonesians await vote count

- Published

Nearly 190 million Indonesians were eligible to vote

When Indonesians went to the polls on 9 July, most knew it would be an election unlike any the country had ever seen.

In 16 years of democracy, the faces on the ballots had been dominated by those from the military and political elites - but not this time around.

This election featured Joko Widodo as a candidate - a politician so far removed from those circles that at times the parties backing him seemed to be sitting out the campaign season.

His opponent, former general Prabowo Subianto, on the other hand, commanded the army special forces under Suharto's dictatorship. This was his second time on the ballot, and his well-funded campaign was backed by a coalition of political parties that had secured 60% of parliamentary seats.

The starkly different candidates made for heated conversations over family dinners, spurred unprecedented public interest in politics and divided the country.

But few had predicted that by the end of polling day both candidates would claim victory.

Now the Election Commission in the world's third-largest democracy has the unenviable task of counting the results from nearly half a million polling stations across some 8,000 islands - in front of a nation fixated on the result.

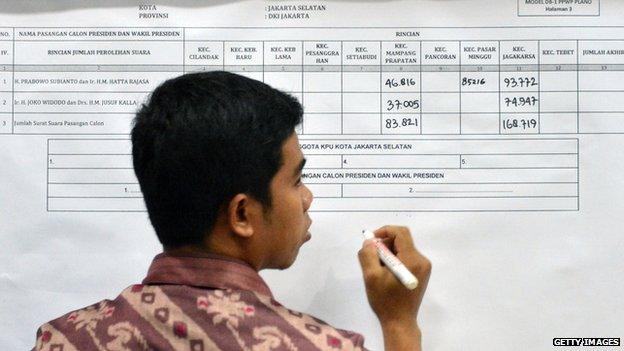

With nearly half a million polling stations, the Election Commission faces a mammoth task in counting votes

Both Prabowo Subianto (L) and Joko Widodo (R) have claimed victory in the presidential election

Bad maths?

The process began in each polling station. As soon as voting ended, officials counted the ballots in front of anyone who cared to watch.

In a middle-class neighbourhood in south Jakarta, eagle-eyed witnesses spotted an error. Some ballots were ruled invalid because the holes punched in the paper were too big, even though the punctures appeared to sit within the boxed area as required in the voting guidelines.

To ensure transparency, the Election Commission has been uploading forms that show the results from all polling stations to its website.

But it gets difficult to monitor from there. The numbers get tabulated at village, sub-district, district and provincial levels before a national result can be concluded.

Unwilling to trust the process, a crowd-sourcing project called kawalpemilu.org, external attracted some 700 volunteers to add the numbers themselves from the forms on the Election Commission website.

So far, the netizens have processed results from 92% of all polling stations, giving Jokowi, as Mr Widodo is known, a 53% lead over his rival's 47%.

But the Election Commission data has also raised questions about the competency or legitimacy of some polling stations' vote counts.

A number of forms show that the votes for the two candidates and spoiled ballots do not add up, either deliberately or because of someone's bad basic maths.

One form shows an X mark for a blank space turned into a number 8, giving the Prabowo ticket 800 extra votes. His campaign team dismissed it as human error.

More crucially, forms from a village of more than 7,000 people in the populous province of East Java show 100% voter turnout with all votes for Prabowo.

Similarly, many polling stations in Indonesia's most remote provinces of Papua and West Papua also reported 100% turnout, with all votes going to Jokowi.

The poll, which had taken place across hundreds of islands, is a major logistical challenge

Votes must be counted at various levels before an official result can be concluded

'Professional suicide'

The chaotic process of ensuring the legitimacy of the numbers at the various levels of government has prompted the election authorities to allow the publication of early results through quick counts.

The counts are based on real results from selected sampling of polling stations that represent the voting trend. Some organisations have been able to produce very close estimates over the years. It is therefore considered a crucial way to independently keep track of the official counting process.

Burhanuddin Muhtadi heads up one of the certified quick count groups, Indikator Politik Indonesia. His group, along with most others, predicted a Jokowi win.

But four other pollsters contradicted their findings.

When the Association of Public Pollsters ran an audit of the groups' methods, those that predicted Prabowo's victory refused to be audited.

Prabowo's team pointed out that Muhtadi and other pollsters with favourable results for Jokowi, and some of the association's auditors, were openly Jokowi supporters.

"I don't see any conflict of interest," Muhtadi said of the accusation against him. "If my quick count said Prabowo was winning I would've showed it. Sacrificing my objectivity for my personal preference is like professional suicide. This is what I do for a living."

Pollsters that predicted a Prabowo victory could not be reached for comment, but one of them, Puskaptis, said in a statement that it had asked all survey groups to agree to be dissolved if their predictions are proven wrong on 22 July, when official results will be announced.

When Indonesians finally hear the result, the credibility of many could be lost or tested. The strength of Indonesia's democracy may be too.

- Published9 July 2014

- Published7 July 2014

- Published3 July 2014

- Published10 July 2014