'Grave concerns' over Australia asylum centre - top rights official

- Published

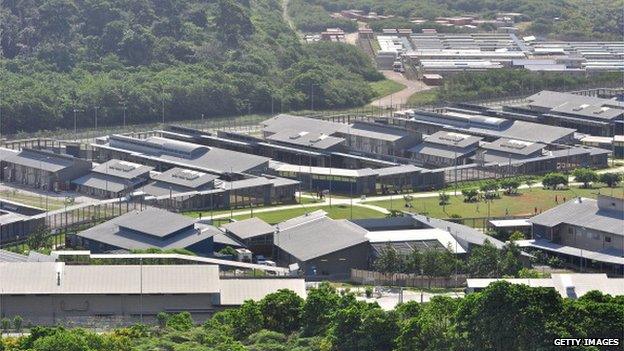

Australia's human rights commission says there are 1,102 asylum seekers at Christmas Island's detention camp

Australia's top rights official says the situation at the Christmas Island asylum detention centre has "significantly deteriorated", leaving people "plagued by despair".

Gillian Triggs visited the centre on 14 July after reports of several incidents of self-harm or suicidal detainees.

She voiced grave concern over "a spike" in self-harm cases and for the welfare of babies and young children.

She also called for children and families to be moved to the mainland.

The Australian government has come under fire from human rights representatives in recent months for its tough asylum policies.

The government has disputed some of the assessments Prof Triggs' team made, including the extent of illness among children. It pointed out it had already reduced the number of children in detention.

Australia and asylum

Asylum-seekers - mainly from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Iran - travel to Australia's Christmas Island on rickety boats from Indonesia

The number of boats rose sharply in 2012 and the beginning of 2013, and scores of people have died making the journey

Everyone who arrives is detained. The previous government reintroduced offshore processing in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Those found to be refugees will be resettled in PNG, not Australia

The new government has toughened policy further, putting the military in charge of asylum operations and towing boats back to Indonesia

Rights groups and the UN have voiced serious concerns about the policies. Australia says no new asylum boats have arrived for 200 days

'Helplessness'

The visit by Australia's human rights commissioner to the detention camp came about a year after the government instituted a policy that no asylum seeker arriving by boat could settle in Australia, if found to be a refugee.

There are currently 1,102 asylum seekers housed on Christmas Island and 174 of them are children, according to the commission., external Most of them have not yet had their claims for refugee status assessed.

"In the four months since we visited Christmas Island, the situation for asylum seekers has significantly deteriorated," Prof Triggs said.

"They are plagued by despair and helplessness at the seemingly endless period of detention."

Ten women required a 24-hour suicide watch, when previously there were only one or two per week which required such monitoring, the commission said.

It attributed this spike to increased tension since 7 July when several mothers called a meeting with officials to see if they could be moved to mainland detention, so that their babies could have space to learn how to crawl or walk.

The mothers were "confined in the extreme heat" in metal containers measuring 3m by 3m, which each contained a bunk bed and a cot, leaving only 1 sq m of space, the commission said.

The plight of children in the camp was particularly dire, according to the team.

A paediatrician who accompanied the team said "most" of the infants and young children were ill and had chest or gut infections. She noted cases of recurrent asthma and irritation of eyes and skin.

She attributed this to cramped and unhygienic living conditions, and said the camp's air was contaminated with phosphate dust from a local mine.

Many children appeared to have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, including nightmares, flashbacks, bed-wetting, stuttering and refusal to eat, the doctor, Professor Elizabeth Elliott, said.

Asylum seekers sailing to Christmas Island often arrive in rickety boats and have to be assisted by the navy

The rights commission condemned conditions, particularly for mothers and babies, at Christmas Island

A spokesman for Immigration and Border Protection Minister Scott Morrison however disputed parts of the commission's account.

In remarks e-mailed to the BBC, the spokesman said that chest and gut infections are "not pervasive", and that any illness was treated with appropriate medical support.

The spokesman added that Christmas Island detainees had access to healthcare that was "commensurate" with that provided to Australians.

The spokesman noted that the number of children in detention on Christmas Island had declined by 60% since the Liberal-National coalition took power last year, and said there were currently 153 children in the camp.

Australia takes a tough approach to asylum seekers who try to reach the country by perilous sea journeys. The asylum boats mainly depart from Indonesia and try to reach Christmas Island, which is the closest Australian territory.

Under current policy, asylum seekers who arrive by boat are sent to detention camps in Papua New Guinea (PNG) or Nauru. If found to be refugees, they will be resettled there, not in Australia.

The UN and rights groups have condemned conditions in the PNG and Nauru camps.

- Published31 October 2017

- Published19 July 2013

- Published7 July 2014

- Published29 July 2013

- Published26 May 2014

.jpg)