Profile: Khmer Rouge leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan

- Published

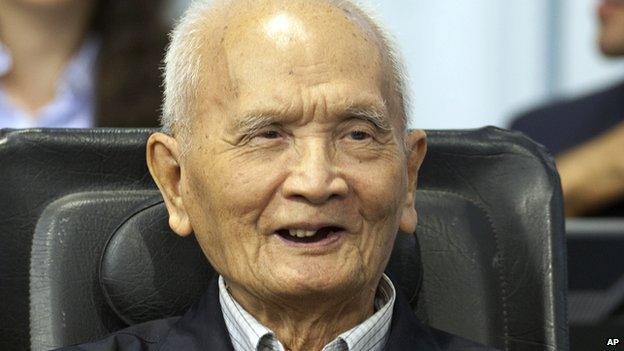

Khieu Samphan (left) and Nuon Chea are the last surviving top leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime

They were once considered the Khmer Rouge's most powerful leaders after Pol Pot.

Now Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan have been jailed for life after being convicted by Cambodia's UN-backed tribunal of crimes against humanity.

The verdict comes more than three decades after the Khmer Rouge's fall. Under the regime, up to two million Cambodians died from execution, overwork and starvation.

The pair are also on trial for genocide. The cases are being tried separately to accelerate proceedings because the defendants are elderly.

Two other defendants were on trial - Ieng Sary has died and Ieng Thirith has been declared unfit to stand trial.

Khieu Samphan (left, seen in 1985) served as president during the Khmer Rouge's rule from 1975 until 1979

Nuon Chea (seen here in 1998) was second in line to Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot

Nuon Chea, "Brother Number Two"

Born to a corn farmer and a seamstress, Nuon Chea was second in command to Pol Pot.

Serving as chief ideologist, he is believed to have played an integral part in shaping the Maoist regime's radical thinking.

Prosecutors say Nuon Chea was one of a small group behind policies that drove city residents into forced labour and starvation in the countryside, and used systematic violence against perceived enemies of the regime.

After the Khmer Rouge fell, he moved with its remaining fighters to strongholds in north-west Cambodia until in 1998 he was granted a pardon by Prime Minister Hun Sen as part of a peace deal.

However, after international pressure, he was arrested in 2007 and subsequently put on trial.

As chief political thinker of the Khmer Rouge, Nuon Chea pursued a radical communist ideology

When the trial opened in November 2011, International Co-Prosecutor Andrew Cayley said the control exercised by the regime's top leaders "over all aspects of Cambodian society was frightening, pervasive and complete".

"The accused were informed of everything, from the number of couples married each month, to how much it rained, to the identity of persons who complained about the party's cooperative programme and lack of food.

"If the accused wanted an orange from Pursat, it would be picked and delivered to them. But if a parent sought to pick some fruit or catch a fish for a starving child, they would be arrested, reported to Angkar [the regime] and sent for re-education.

"Death might come swiftly, but not swiftly enough to spare the torture."

The crimes that occurred were not "random events attributable to rogue cadres" or solely to be blamed on Pol Pot, the prosecutor went on.

"These crimes were the result of organised plans developed by the accused and other CPK [Khmer Rouge] leaders and systematically implemented through the regional, military and government bodies they controlled."

Nuon Chea denied the charges against him, saying as the trial ended that he never ordered Khmer Rouge cadres "to mistreat or kill people, to deprive them of food or commit any genocide".

Responding to testimony from relatives of those who died, he said: "As a leader, I must take responsibility for the damage, the danger to my nation."

"I feel remorseful for the crimes that were committed intentionally or unintentionally, whether or not I had known about it or not known about it."

Khieu Samphan

Khieu Samphan served as Cambodian president from 11 April 1976 to 7 January, 1979.

He was brought up in southeast Svay Rieng province and educated in France, where he became a prominent member of a leftist Khmer student intellectual group in the 1950s.

During his time in office, Khieu Samphan was the public face of regime and accompanied overseas diplomats on official visits.

Khieu Samphan insisted he played no direct role in deaths under the Khmer Rouge

Like Nuon Chea, he is accused of helping sculpt some of the regime's deadliest policies as one of its top leaders.

"He publicly endorsed taking measures against the enemies of the revolution in a way that suggests knowledge and support of the policy of executing purported enemy agents," Stephen Heder and Brian Tittemore wrote in their book, "Seven Candidates for Prosecution".

But Khieu Samphan says he should not be held responsible.

"It is easy to say that I should have known everything, I should have understood everything and thus I could have intervened or rectified the situation at the time,'' he told the court.

"Do you really think that that was what I wanted to happen to my people? The reality was that I did not have any power," he said.

- Published30 July 2014

- Published31 May 2013

- Published21 October 2013

- Published14 March 2013