Why is Sanskrit so controversial?

- Published

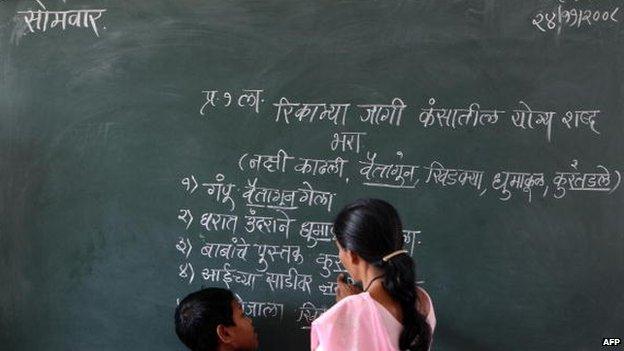

Many Indian languages, including Marathi, originate from Sanskrit

India's new government focus on Sanskrit has sparked a fresh debate over the role language plays in the lives of the country's religious and linguistic minorities.

Inside a brightly lit classroom at Delhi's Laxman Public school, a group of students sing a Sanskrit hymn.

Across the corridor, in another classroom, a group of grade eight students are being taught Vedic Mathematics, which dates back to a time in ancient India when Sanskrit was the main language used by scholars.

It is all part of Sanskrit week - a celebration of the classical language across hundreds of schools mandated by India's new federal right-wing government.

"It's our mother language, the root of all our languages," says Usha Ram, the school principal.

"All over the world people try to preserve their traditions. Why not in India?"

Sanskrit is a language which belongs to the Indo-Aryan group and is the root of many, but not all Indian languages.

"If you know Sanskrit, you can easily understand many Indian languages such as Hindi, Bengali and Marathi," says Vaishnav, a grade 11 student at Laxman Public School.

But Sanskrit is now spoken by less than 1% of Indians and is mostly used by Hindu priests during religious ceremonies.

It's one of the official languages in only one Indian state, Uttarakhand in the north, which is dotted with historical Hindu temple towns.

According to the last census, 14,000 people described Sanskrit as their primary language, with almost no speakers in the country's north-east, Orissa, Jammu and Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and even Gujarat.

The government has encouraged schools to take part in reading, writing and speaking activities for Sanskrit week.

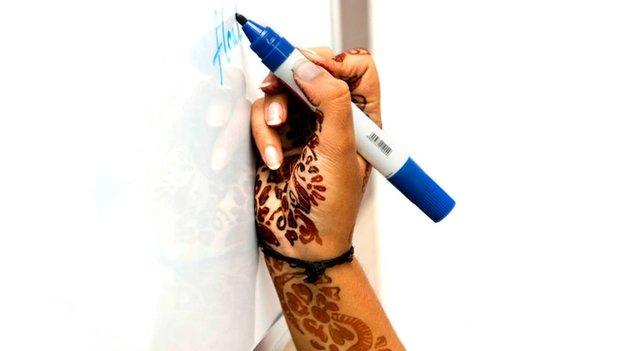

Sanskrit is offered as an optional language in schools in India

In schools, it is only offered as an optional language, with most students preferring to choose more relevant languages, including French, German and even Mandarin, which are seen as more appropriate in a globalised world.

It is also often taught very badly. Like many Indians, I studied Sanskrit in high school. But place a text in front of me and it is barely comprehensible.

But reviving the ancient language, which is so closely linked to Hinduism and Hindu religious texts, has always been a pet project for the BJP, the right-wing party that leads the new Indian government.

In May, several of its new cabinet ministers chose to take their oath of office in Sanskrit.

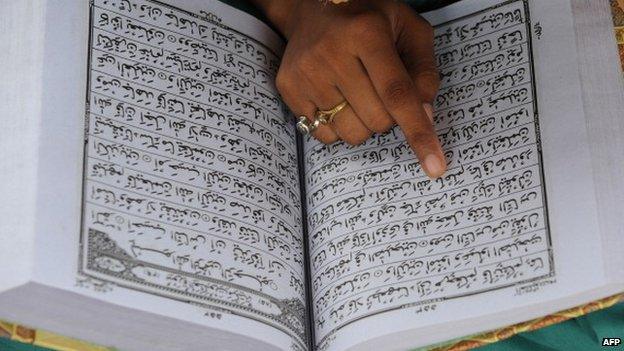

Many children choose to learn other languages

Muslims in India choose to learn Arabic

"Sanskrit and Indian culture are intertwined as most of the indigenous knowledge is available in this language," says a government leaflet sent out ordering schools to observe Sanskrit week.

But it is precisely this fusion that is stirring up a new controversy in a country where language politics has always been an emotive and sensitive issue.

It is being opposed most strongly by politicians from the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

The Tamil language is not derived from Sanskrit and many there see the promotion of the language as a move by Hindu nationalist groups to impose their culture on religious and linguistic minorities.

"We want an inclusive India, a secular India, an India that belongs to everybody," says Kanimozhi, a Tamil member of parliament from the regional DMK party.

But this is an argument that is heavily contested.

"People have a misunderstanding that it is the language of the Hindus," says Markandaya Katju, a retired Supreme Court Judge.

"Ninety-five per cent of Sanskrit literature has nothing to do with religion."

It's a debate that's unlikely to end any time soon in a country which boasts of several hundred languages and dialects.

And while the government says it has no hidden agenda, there are some who wonder if the motive is to educate or to indoctrinate young minds.

- Published19 May 2014

- Published30 July 2013

- Published27 November 2012