Can Indonesia's Jokowi meet expectations?

- Published

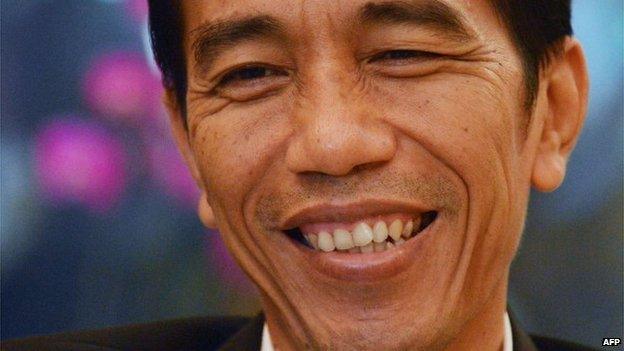

Voters expect much from Jokowi, but can he govern at national as well as local level?

Political analyst Tobias Basuki likes to tell a story about Indonesian President-elect Joko Widodo that has perhaps been embellished over the years but shows why so many people have such high hopes for the country's next leader.

A few years ago, Jokowi, as the president-elect is known, was named by the magazine Tempo as one of Indonesia's 10 best regional politicians.

At the time, he was the mayor of Solo, a city on the island of Java.

Mr Widodo was invited to the magazine's office for an interview and a reporter apparently found him in the lobby sitting on his own, without the entourage that usually accompanies Indonesian politicians.

As Mr Basuki tells it, Jokowi looked like a commoner, someone's driver. "Who are you?" asked the journalist.

The future president-elect then stood up and bowed politely as he offered the reporter his name card. The image of Joko Widodo as a humble public servant was born.

Mr Widodo's down-to-earth leadership style has won him supporters

'Most honest politician'

This unassuming style was Jokowi's hallmark during his time as Solo's mayor and then as governor of Jakarta from 2012, a post he still held when he won Indonesia's presidential election in July.

He won the poll with 53% of the vote over his rival, Prabowo Subianto, who got 47%.

"His down-to-earth style of leadership is new in Indonesian politics. There seems no gap between him and the people he leads," said Mr Basuki, of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta.

But style can only get you so far, there has to be substance. Joko Widodo also has an enviable record in getting things done.

For his work as mayor of Solo, Jokowi came third in the World Mayor Prize of 2012, an annual award given to leaders who have revitalised their cities.

This is what the judges said about Jokowi, who did not draw his salary while he was mayor: "Joko Widodo turned a crime-ridden city into a regional centre for arts and culture, which has started to attract international tourism.

"His campaign against corruption earned him the reputation of being the most honest politician in Indonesia."

Many Indonesian politicians, like election rival Prabowo Subianto, have less accessible public images

Jokowi has burnished that reputation during his short time as governor of capital, Jakarta.

He built new homes for people living in some of the many slums dotted around the city, initiated projects to alleviate the flooding and introduced a scheme to give poorer people virtually free health care.

He also re-started building work on a badly-needed metro system for the traffic-clogged city.

.jpg)

As Jakarta Governor, Mr Widodo successfully delivered on promises he made during campaign speeches

His supporters are not hard to find, particularly in a poor area called Tanah Tinggi in central Jakarta.

In this densely-populated space, chickens peck around the feet of chatting neighbours. In the heat, flies buzz around food laid out for sale on stalls all along the narrow streets.

Rooms inside the small homes are dark and sparsely furnished but in an area of the slum stands a group of neat, two-storey homes built of concrete that have running water and indoor toilets.

Jokowi built these houses shortly after becoming Jakarta's mayor in order to re-house some of the people living in Tanah Tinggi.

Thirty-eight-year-old Marlina and her family were some of the lucky ones to get a new house.

"All I know is that it was Mr Jokowi who built my house and we didn't have to pay a cent," Marlina said, as she turned on the tap to show off her home's facilities.

Flooding, as a result of poor drainage systems, continues to plague many Indonesian cities

Mounting challenges

But when he becomes president in October, Mr Widodo faces a series of pressing problems, not least the massive fuel subsidy that keeps petrol so cheap in Indonesia.

The government spends three times as much on this as it does on infrastructure construction.

Mr Widodo has promised to phase out the fuel subsidy and use the money for the poor but that proposal has already upset motorists.

There are also wider issues to tackle, including poverty. Indonesia has more than 100 million people who survive on $2 (£1.20) a day or less.

Many residents of Tanah Tinggi face poor and dangerous living conditions

Nurhayati (pictured right) and her family live beside a railway line that runs alongside Tanah Tinggi

Some of those people live right next to a railway line that runs alongside Tanah Tinggi, within touching distance of the trains that pass by.

Families live in temporary shelters, made from tarpaulin and odd bits of wood. Every now and then, railway authorities arrive to chase people away and destroy their homes, but those who live there simply return.

They earn a living by scavenging, sorting through rubbish looking for plastic bottles to sell.

Nurhayati is one of them. She came to Jakarta as a migrant with her mother from eastern Java when she was just 13.

Now 21, she has two children who play alongside the railway tracks as trains rush pass.

"The price we get for bottles has fallen recently," she said.

Over the longer term, helping people such as Nurhayati is going to be Mr Widodo's most difficult task.

Peter Carey, a visiting professor at the University of Indonesia in Jakarta, said the economy had grown rapidly over the last decade and Indonesia was soon expected to become one of the world's richest countries.

But he said there needed to be a real desire within the government to provide people with proper health care, a better education system and a co-ordinated transport network - and deal with the country's notorious corruption.

"Indonesia has a huge income gap to close. What's the point in becoming so rich if none of this wealth is used for the benefit of the people of this country," he said.

- Published13 February 2024

- Published22 July 2014

- Published22 July 2014

- Published23 January 2013