Vietnam's forgotten Cambodian war

- Published

Vietnamese veterans like Nguyen Thanh Nhan (Bottom, first from left) are still haunted by the war

On 30 April 1975, the last American helicopters beat an ignominious retreat from Saigon as the tanks of the North Vietnamese Army rumbled into the capital of defeated South Vietnam.

Victory over the US military is remembered each year in Vietnam as a triumph over foreign aggression in a war of national liberation.

Less celebrated is Vietnam's quiet retreat from its own deeply unpopular foreign war that ended 25 years ago this month. A war where Vietnamese troops, sent as saviours but soon seen as invaders, paid a steep price in lives and limbs during a gruelling decade-long guerilla conflict.

On the 25th anniversary of their withdrawal from Cambodia, Vietnamese veterans are still haunted by their memories of war with Pol Pot's army.

Some wonder why Cambodians are not more grateful to the troops who freed them from the brutal Khmer Rouge regime.

"Anyone who came back from Cambodia intact was a lucky person," said Nguyen Thanh Nhan, 50, a veteran of the war and author of the autobiographical book "Away from Home Season - The Story of a Vietnamese Volunteer Veteran in Cambodia".

Sent to Cambodia at the age of 20, Mr Nhan served from 1984 to 1987 in a frontline combat unit near the Thai-Cambodian border where some of the bloodiest confrontations with Khmer Rouge fighters took place.

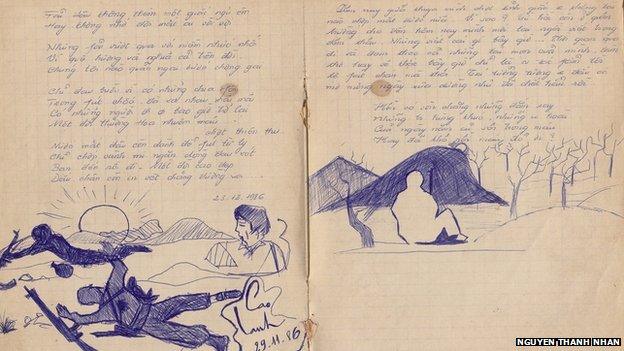

Mr Nhan has kept detailed accounts of the war, including this diary entry recounting a 1986 battle

Though the Vietnamese government has never officially confirmed casualty numbers, some 30,000 Vietnamese troops were believed to have been killed before the final withdrawal in September 1989.

Banned in its original form by the Vietnamese government, Mr Nhan's book recounts the hardships of the Vietnamese soldiers and their camaraderie while trying to survive among a population who played host to them by day, and their enemy by night.

Much like the young Americans who fought in Vietnam, Mr Nhan's years in Cambodia have left indelible psychological marks. He still suffers from nightmares, and their daytime equivalent that drag him back into the terror of battle.

"When your companions die in battle, it is a very great loss," Mr Nhan said. "During the war, the battle does not stop. We have no time to reflect. We must be strong to continue. Later, more than 30 years later, memories come back - over and over again."

"The injury in the body is not so heavy but our injury was mental. Many soldiers, one or two years later, when they came back, they went mad."

His experience parallels the disillusionment of American troops, a generation before who arrived in Vietnam believing they were coming to save a nation, only to find that many ordinary people considered them the enemy.

"American soldiers thought they helped Vietnam. Then their illusion was broken," Mr Nhan said. "We were the same in Cambodia."

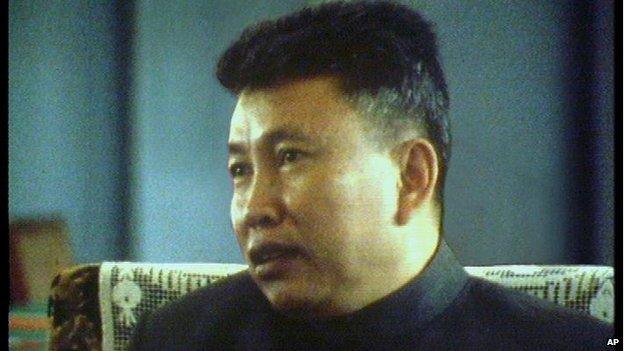

Pol Pot led the Khmer Rouge in a wave of killing

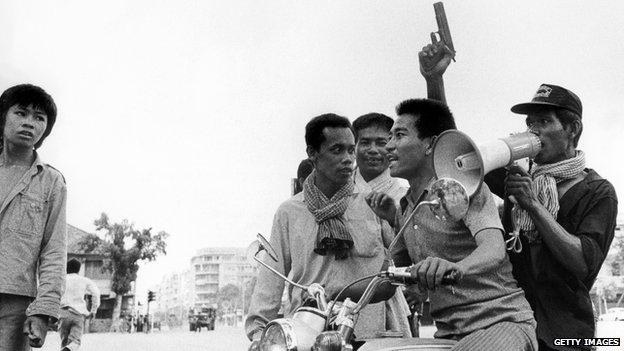

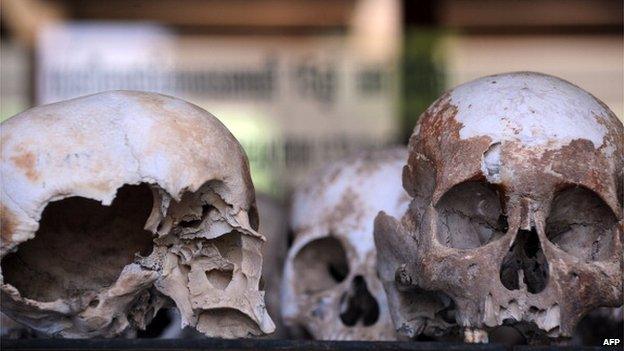

The Khmer Rouge forced millions of Cambodians out of the city and into the countryside

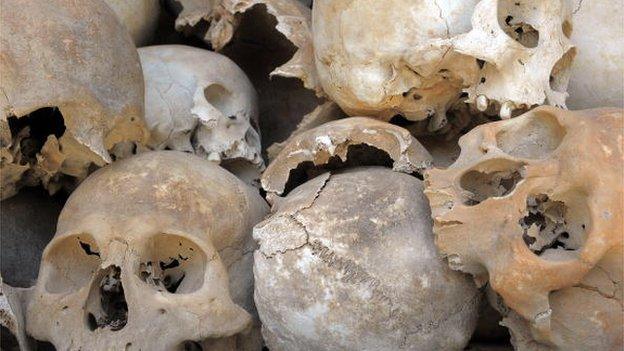

Up to two million people are believed to have died under the Khmer Rouge

Vietnam launched an invasion of Cambodia in late December 1978 to remove Pol Pot. Two million Cambodians had died at the hands of his Khmer Rouge regime and Pol Pot's troops had conducted bloody cross-border raids into Vietnam, Cambodia's historic enemy, massacring civilians and torching villages.

Pol Pot fled ahead of the onslaught and Phnom Penh was placed under Vietnamese control in a little over a week.

Those that survived the Khmer Rouge regime initially greeted the Vietnamese as liberators. Years later, however, Vietnamese troops were still in Cambodia and by then, many Cambodians considered them occupiers.

Cambodia was an unpopular war for Vietnam, said Carlyle Thayer, an expert on Vietnam and emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra.

"The Vietnamese military had been trained and experienced in overthrowing an occupying power and all of a sudden, the shoe was on the other foot. They had to invade Cambodia and occupy it, and succeed in setting up a government and engineer a withdrawal."

Unlike Vietnam's wars against the French and Americans, the intervention in Cambodia was "downplayed" to the Vietnamese public, Mr Thayer said. When soldiers returned from Cambodia without the fanfare of previous wars, veterans felt that they had been "forgotten".

Gratitude was also not forthcoming from Cambodia, where hostility towards the Vietnamese remains ubiquitous. It is an enmity born of conflicts between ancient emperors and kings, of lost territory and a much smaller Cambodia faring poorly through history to a far more populous Vietnam.

Today, many in Cambodia would like to forget that it was Vietnam that saved their country from Pol Pot's vicious revolution.

A propaganda poster from the 1980s depicts Cambodian-Vietnamese relations

The Friendship Monument in Phnom Penh commemorates Vietnam's role in defeating Pol Pot

Following Vietnam's withdrawal from Cambodia, soldiers' remains were removed from this war cemetery

Every few months, a group of veterans from the war in Cambodia meet in Ho Chi Minh City. On a recent Sunday morning, their get-together started early with short welcome speeches followed by swift toasts of strong rice wine.

Asked about the war, their mood shifted perceptibly. What happened in Cambodia is not something they discuss often.

One relents, likely out of politeness, and he describes an enduring image from his first days in Cambodia in 1979.

Le Thanh Hieu's unit pursued the retreating Khmer Rouge to the border with Thailand. He remembers seeing Cambodian villagers lying on the sides of roads dying of starvation and illness.

"They were dying everywhere. They were dying of hunger," said the 54-year-old. "We didn't have rice to feed the starving. We only had army rations to feed ourselves in battle."

Yet, he said, "faced with this situation the soldiers could not avoid saving lives" and they used their rations to make a thin rice soup for the starving.

"I don't want to have this experience to tell you about," Mr Hieu said.

Vietnam does not want to entirely forget about the war in Cambodia, said Mr Nhan. It only wants to remember an official version: a victorious, lightning attack that toppled Pol Pot.

Best forgotten, Mr Nhan said, are the 10 years of punishing hit-and-run fighting and the largely-forgotten veterans still scarred from their experiences.

"For me, the truth needs to be said," he said.

"Sometimes I think the dead are lucky. They rest in peace. We have to struggle every day. Our lives continue."

- Published16 November 2018