Naval epic takes South Korea by storm

- Published

The movie tells the story of a Korean naval officer who defeated Japan's imperial navy fleet

When a movie about ancient historical events breaks all box-office records, you have to ask what's going on.

The Admiral: Roaring Currents, external depicts a figure from the 16th Century but despite its distant pedigree, it's now the biggest film in the history of Korean cinema, outdoing Hollywood imports and Korean movies alike.

The ancient history has not turned contemporary Koreans away from the film but instead drawn them towards it.

It is true that the film is a shrieking adventure of gore and death, and that has popular appeal - but it is also about the defeat of the Japanese navy by a Korean admiral, and that has mega-appeal in contemporary South Korea.

The film depicts the Korean naval leader Yi Sun-sin, who, despite being severely outnumbered, defeated the Japanese fleet.

Today's Koreans have been crowding out cinemas to see it - 17 million people, a third of South Korea's population, have watched since it opened in the summer.

The movie has become one of the most successful films in the history of Korean cinema

'Reconciliation'

As the Hollywood Reporter, external put it: "South Korean epic 'Roaring Currents' rewrote one local box-office opening record after another over its opening weekend, raking in $37.5m (£23.1m) and more than five million admissions in just six days."

Hollywood's trade paper continued ecstatically: "'Roaring Currents' went on to sell the most number of tickets during a weekday ($6.7m or 860,000 admissions) as well as during any single day ($9.5m or 1.25 million admissions) during its first weekend in theatres. It accounted for as much as 87.6% of total tickets sold across the country on Saturday."

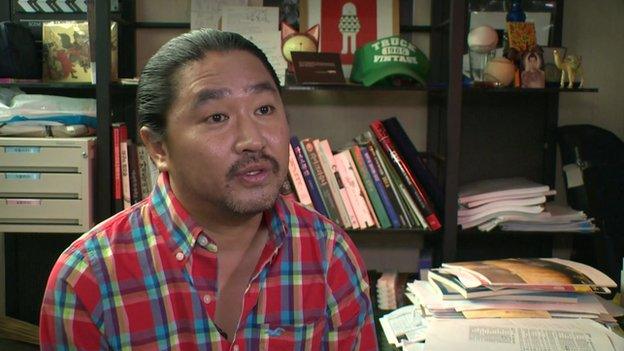

The film's director, Kim Han-min, told the BBC: "I hope that the Japanese through this movie will learn about their past history so that the whole region can come closer together."

Unlikely as it seems, he thought the film would lead to reconciliation between the two neighbours.

Mr Kim hopes the film will play a part in facilitating reconciliation between Japan and South Korea

His reasoning was that Japan glossed over its own past as a coloniser of Korea in the first half of the 20th Century and as a perpetrator of outrages in World War Two - and his attempt at depicting Japan's defeat would bring enlightenment and gratitude among the Japanese population.

He said: "I'm not a politician or an academic. I'm only a movie director but during times of bad relations between countries I think culture can bridge the gap."

'Negative feeling'

It seems a forlorn hope that this particular gap can be narrowed by this particular film.

The physical distance between the two countries at its narrowest is about 200km (124 miles) but the way the director tells it, the cultural gap of animosity is much wider.

A BBC poll, external last year had only one in five South Koreans holding a positive view of Japan and about the same proportion of Japanese thinking well of South Korea.

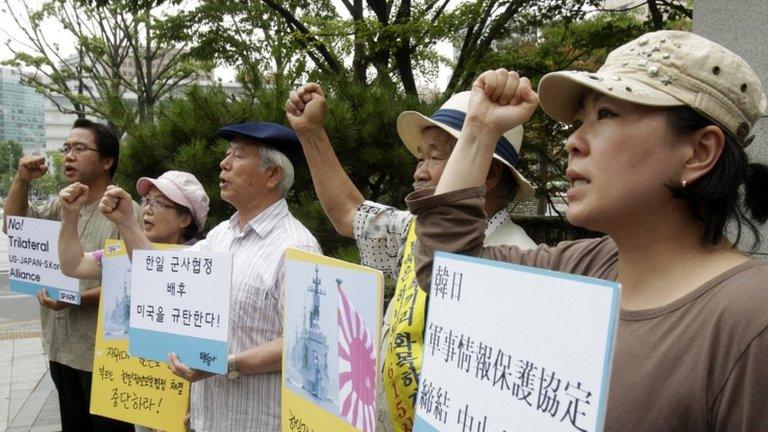

Tensions in East Asia are running high over maritime issues, including a Tokyo-Seoul row over islands

And certainly people emerging from showings in Seoul didn't seem to have narrowed their differences with Japan.

"I haven't felt much negative feeling about modern-day Japan. But having watched the movie, I was reminded about the aggression they've inflicted on this country," one viewer said.

Mr Kim also thinks his film hit the right button in another way. He said the sinking of the Sewol ferry in April, which killed more than 300 people, left many in the country feeling something had gone badly wrong with South Korea. He told the BBC that the film depicted a strong leader and that played well in the current malaise.

So the film does play to Korean views, and plays very well. But there is an alternative view which is that those views are themselves not accurate. The dark impression of Japan is overly dark.

Andrew Salmon, author of Modern Korea, said: "There is a misconception that Japan has never compensated and never been contrite and never apologised for misdeeds during the colonial era, and so this kind of historical story set in the 16th Century resonates now."

He said, though, that Japan had compensated Korea in 1965 for abuses and made more than 50 official apologies. It had also, he said, attempted to compensate the "comfort women" who were forced to act as sex slaves for Japanese soldiers.

.jpg)

The Sewol ferry sinking in April, a major maritime disaster, caused shock and anger in South Korea

He thinks the film does resonate today because of Korean feelings about Japanese deeds, but also because of the Sewol: "It's a maritime epic and there was a very significant maritime drama in April when the Sewol sank with great loss of life."

"But the Sewol was abandoned by its captain and crew and their incompetence and cowardice was responsible for a great loss of life. This story in the film is the opposite. It was about an extremely honourable and heroic figure."

So the film resonates on lots of political levels in South Korea today. It should be said, though, that there can't be many cinema-goers who don't enjoy a rip-roaring yarn, with lots of bangs and clattering.

- Published20 January 2011

- Published4 November 2013

- Published29 June 2012

- Published4 January 2013