Can China become a leading global innovator?

- Published

Can China shed its 'factory of the world' image to become a global innovator?

Assembled in China but designed in California, Japan, or Europe. That's been the story of China's economic rise for the past 30 years.

Few if any of China's companies are considered innovative by global standards - and Nobel prizes for science remain frustratingly elusive.

But China wants to be more than the factory of the world and its government knows it has to move on from a "beg, borrow or steal" strategy on innovation if it is to keep growing its economy. Will it be able to do this?

The Innovators

Husband and wife entrepreneurs Yang Yang and Winnie are working on a prototype for a pen that writes in plastic. Unfortunately, the pen is smoking more than it's writing and the room fills with a foul smell of burning plastic.

China Editor Carrie Gracie visits Shenzhen to meet its various entrepreneurs

I'm in Shenzhen, China's answer to Silicon Valley and its most entrepreneurial city.

I've tracked down these young inventors at one of China's first meeting places for business start-ups.

"Really horrible, I know. But I've only been working on this for two weeks," laughs Yang Yang as we stand back from the smoking shreds of green plastic on the work bench.

Higher wages

Prof Xue Lan, head of Qinghua University's School of Public Policy and Management, explained why constraints on resources and labour, not to mention China's environment, make innovation a necessity and not a choice.

"The best way and the only way China can maintain development …. is much less resource depletion, with much more efficient use of resources and also paying higher wages," he said. "For all of those, you have to rely on innovation."

The city of Shenzhen has often been hailed as China's answer to Silicon Valley

Professor Xue is preaching to the converted.

Hardly a day goes by without one or other of China's top leaders making a speech about the need to transform the economy through innovation.

The government now spends over 1tr yuan ($162bn: £100bn) annually on research.

China's position in global innovation rankings is improving but it is still outside the top 25 countries on most indices - a weak performance for the world's second biggest economy.

China has yet to be ranked highly in terms of global innovation

So what are the barriers? A question I put to the young innovators in Shenzhen.

They all came up with the same answers: money and culture.

"Unless you have a solid prototype to actually demonstrate, you won't get very far. The banks are very conservative about this kind of business model."

China's banks are mostly controlled by the state and rarely lend to small companies, let alone to start-ups.

Instead, they deal with the big state-owned companies for what critics say are often political rather than business reasons.

As for culture, Zhang Hao may have scoured California, Europe and Japan for ideas and developed a robot which can see 3D objects and react in real time. But he's finding human recruits a bigger challenge. Chinese culture is risk-averse.

"I had an intern, and we actually spent a lot of time talking to each other over email," he said. "But in the end, he refused to join, saying that his family thought my company was too insecure."

Old habits die hard

So what of the big companies?

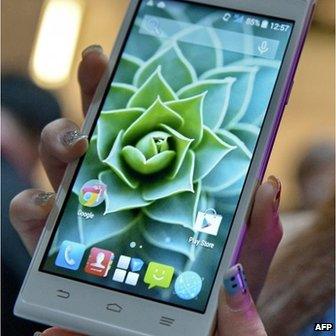

ZTE is seen as one of China's more innovate companies

If China is to make it to the innovation top table, it needs not just the bedroom start-ups but the big companies which can develop and scale up a good idea.

I visited mobile phone giant ZTE which says it puts innovation at the heart of its brand. The company files more than 2,000 patents a year and spends about £1bn annually on innovation.

As we walked through ZTE's showroom, I asked its director of corporate strategy, Sun Zhenge, whether the company has plans for a breakthrough product that will change lives and define a new market.

"We are proud to announce that we have the best picture quality cell phone worldwide," Dr Sun said.

Dr Sun went on to explain advances in security and payment features on the next generation of phones. But even here, one of China's most innovative companies, there are those who say you have to look elsewhere for radical breakthroughs.

I found Chang Bin, one of the company's global research and development workforce of 30,000, hard at work ironing out glitches in the 4G network. He gave me this candid assessment.

"I think maybe Apple generates more creative ideas that change the way we live. Currently our innovation is mostly focused on how to solve concrete problems in existing systems."

Arguably this is what has made ZTE a global success story: taking somebody else's big idea and working on the small incremental innovations to deliver it to market faster or cheaper involves fewer risks than striking out on something radically new.

Being risk-averse is a hard habit to change.

C is for classrooms and creativity

Similar problems apply even in the absence of commercial pressures.

Prof Rao Yi of Beijing University says Chinese culture works against innovation in the awarding of academic research grants.

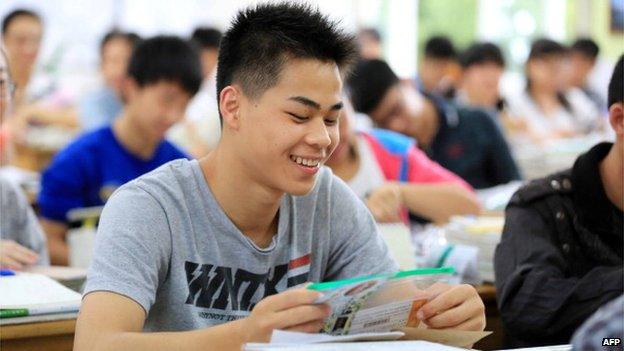

China's annual "gaokao" academic examinations admit aspiring students into universities

"There are always reviewers trying to exclude the very best… and trying to find the second, third, fourth, fifth best, because they feel they are closer to the level of us than the guy who came out with the best idea. We should shoot him down, try not to make him too full of himself.

"Now that's a very bad kind of culture, that's entirely against the idea of innovation in science and technology."

China's barriers to innovation go even deeper.

A key priority is tackling the school system.

Carrie Gracie reports from China on the fear that China's 'exam factory' school system is stunting innovation and creativity

Teacher and educational consultant Jiang Xueqin, said that the exam which 18-year-olds sit - the dreaded gaokao - crushes the openness, diversity and risk-taking that might otherwise feed a culture of innovation.

"High school… is basically a military boot camp for test takers… All they do is they eat, they sleep, and they dream the gaokao. And all they're doing is basically memorising answers."

The young Shenzhen entrepreneurs shudder when I ask them about their gaokao years.

Zhang Hao prefers to look forward. He's optimistic about the future for himself and the more innovative China his generation will create.

"This generation will be the group of people who actually push China forward. We are responsible for the future of the country, where it will go."

It's hard not to be affected by this enthusiasm.

Of course, these inventors are a small like-minded community in one corner of the country, but they do represent something new - an emerging creative generation, exactly what the Chinese government says it wants and what so many observers agree that China needs.

Be careful what you wish for

Will China adapt its one-party political system for the sake of global innovation?

Is this a turning point? A China which is prepared to change everything from education to economic structures for the sake of innovation?

It's very hard to judge.

Jiang Xueqin warned that looking further into China's future, a culture of innovation may bring risks for the country's authoritarian one-party political system.

We know that the creative classes push boundaries, they ask questions, they question authority, that's how they become creative….this means the transformation of Chinese society. And the political system.

The government wants innovation, but it also wants control and no-one yet knows whether it can have both.

This is the paradox at the heart of China's future.

- Published26 March 2014

- Published20 January 2014

- Published30 October 2012

- Published11 November 2013