Tiny islands key to ownership of South China Sea

- Published

The Chinese claim the Paracel Islands

South East Asia says it's "seriously concerned" about China's building of artificial islands in disputed parts of the South China Sea.

In response, China says it's "severely concerned" about the South East Asian nations' statement.

South East Asia says China's actions have "eroded trust and confidence and may undermine peace, security and stability".

China retorts that what it's doing is "entirely legal and shouldn't be questioned".

Are the gloves coming off in the South China Sea disputes?

China has reacted angrily to a formal statement issued on Monday by the 10 countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations, criticising its huge island-building programme in the Spratly Islands.

China is using dredging ships and construction teams to turn at least six coral reefs into large bases with harbours.

One will have a 2,900-metre (1.8-mile) long runway.

There is widening concern that China will use these bases as springboards to assert control over the whole of the South China Sea.

China says it is just protecting its territorial rights and its fishing fleet.

It seems bizarre that some of the smallest islands on the planet now lie at the centre of one the world's biggest territorial disputes.

If they were just a couple of metres lower, they wouldn't even qualify as islands but because they stick up above the surface of the South China Sea, countries can claim them and, more importantly, the territory and the resources in the waters around them.

China is carrying out land reclamation in the Spratlys

Whoever controls the islands will have the strongest claim to the 1.4 million sq miles of the South China Sea and all the fish in it and oil under it.

That's why, for the six countries bordering the sea (seven if you count Taiwan separately), these 250 or so rocks, reefs and islands, with a total area of just six sq miles, are worth all the money and effort they spend on them.

But it's actually about much more than even that.

Two disputes

To understand why American and Chinese ships and planes are confronting each other in the South China Sea it is important to realise that there are actually two different disputes taking place there.

One is about which country owns the features that dot its waters.

The other, more critical dispute is about the future of the international system that has run the world since the end of World War Two.

What international rules should countries follow and who should make them?

It's the overlap between these two disputes - between which country rightfully occupies which islet and which countries set the world's rules - that makes the South China Sea disputes so dangerous.

China has convinced itself that it is the rightful owner of almost the entire sea.

As a result, South East Asian countries with rival claims - Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines - are trying to bolster their position by involving the other big powers - primarily the US, but also Japan and India - on their side.

The US doesn't particularly care which country controls which island, but it's getting drawn into the disputes because of its wider interests.

The authorities in Beijing see things the other way around.

They think the US, anxious to remain the world's leading power, is corralling the countries of East and South East Asia to contain a rising China.

But what concerns the US, and many other countries, is not China's rise, as such, but Beijing's efforts to redefine international law to suit its own interests in the sea.

As a result, the US and its allies and friends are working together to "hold the line". This is where the danger lies.

International challenge

As China tries to extend its control over the water of the sea (as opposed to the islands), it is challenging both the other countries in the region and the international system.

Under current international law - laid down in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea - a country can only own a piece of sea if it owns the land next to it.

A country that owns an island also "owns" 12 nautical miles of seabed around the island and has the rights to the resources (but not the territory) up to 200 nautical miles around.

However, the Chinese government and its state-owned enterprises (particularly oil companies and fishing enterprises) are trying to assert ownership of the South China Sea itself, plus its seabed and its resources, many hundreds of miles away from the Chinese coast.

This is a challenge to the other countries around the sea with claims of their own, to the US whose role as a global military and commercial power depends upon unimpeded access through the world's seas and to every other country that believes in the current rules of international law.

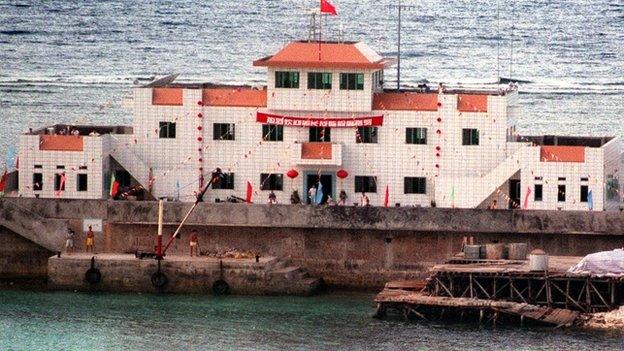

Chinese fort at the Mischief Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands

They say (broadly) that the sea more than 12 nautical miles away from a coast doesn't belong to anyone and is therefore free for anyone to use in any way they see fit. (It's more complicated than that but that's the basic principle.)

Japan needs one oil or gas tanker to cross the South China Sea every six hours to keep its economy functioning; South Korea is similarly dependent on energy imports.

Both countries have other concerns about the way that China is rising too.

Japan has its own dispute with China over the Senkaku/Daioyu islands, sees common cause with Vietnam and the Philippines and has begun supplying both with coastguard ships and other equipment and training to help them defend their maritime claims.

South Korea is less vocal, but also concerned and also supplying weaponry to the Philippines and Indonesia.

India does not depend upon the South China Sea so much, but it fears the consequences if China comes to dominate Asia.

It has two disputes with China over border areas in the Himalayan Mountains.

It is also nervous about China's growing relations with countries around the Indian Ocean and has been developing security ties with Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan and Australia (among others) in response.

20th Century dispute

The Chinese authorities say they have been the historic "owners" of the sea "since ancient times".

The Chinese government's interest in the sea actually only began in the early 20th Century.

For all but the briefest periods of recorded history (one exception is a 30-year period from 1400-1430, during which time the so-called eunuch admirals, including Zheng He, voyaged as far as East Africa) the Chinese authorities were barely able to control their own coastline, let alone islands hundreds of miles away.

Zheng He: The Eunuch Admiral

Zheng He was born in the poor province of Yunnan in 1372 into a Muslim family from Central Asia who had fought for the Mongols.

Captured by the armies of the Ming dynasty, he was castrated at the age of 10.

He was sent to serve the emperor's son, and so distinguished himself in battle that he rose to the rank of admiral.

His armada, bigger than the combined fleets of Europe, featured giant treasure ships 400ft (122m) long and 160ft (50m) wide.

He sailed throughout South East Asia and the Indian Ocean, and on to the Persian Gulf and Africa, creating new navigational maps, and spreading Chinese culture.

He opened up trade routes that are still flourishing today, and gained strategic control over countries that are now once again looking to China as undisputed regional leader.

This version of history is not the one taught in Chinese schools.

This strongly held, but historically unjustified sense of ownership is what is putting China on collision course with its neighbours and the US.

It is the reason why China behaves with such high-handedness when sending oil rigs to drill in disputed waters, for example.

To protect themselves against China's encroachments, other countries are forming new security relationships.

These overlapping interests have the potential to turn a local dispute into a regional or even a global one.

At a time of so many international crises, the South China Sea disputes appear relatively small - but they could get big very quickly.

Changing this behaviour will require the countries of the region to come to a better understanding of the shared history of the South China Sea.

That will be hard but it will be easier than the alternative of escalating conflict and the increasing risk of superpower confrontation.

Bill Hayton is the author of The South China Sea: The struggle for power in Asia, just published by Yale University Press.