Pakistan's bewildering array of militants

- Published

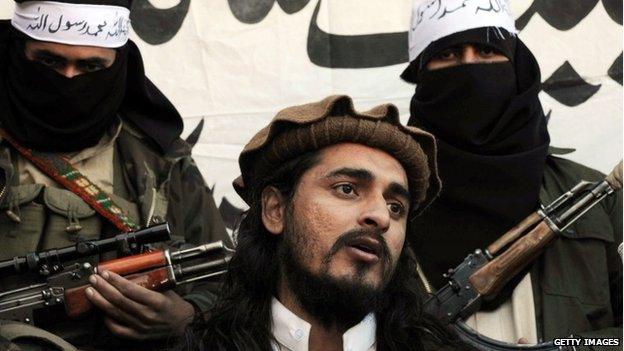

Since TTP leader Hakimullah Mehsud was killed by a US drone last year, splits have worsened

The sacking of Pakistani Taliban (TTP) spokesman Shahidullah Shahid for supporting Islamic State is the latest sign of divisions in an already fragmented militant movement. Over the years Pakistan's insurgents have spawned a bewildering array of splinter groups and factions, reports M Ilyas Khan.

Shahidullah Shahid, as he was known, was the third TTP spokesman to part company with the leadership in recent months.

Before him, Azam Tariq left with the Mehsud faction of Khan Said Sajna that quit the TTP in May. Another predecessor, Ehsanullah Ehsan, became the chief spokesman for a group of Mohmand tribesmen that goes by the name Jamaat-e-Ahrar.

This splintering of the TTP shows that like any other social entity, large and geographically inclusive militant groups also contain sub-groups.

Back in September when the spokesman of the Pakistani army blamed an unknown group of militants - the al-Shura - for carrying out the October 2012 attack on education activist Malala Yousafzai, few eyebrows were raised.

After nearly 35 years of conflict involving non-state actors, Pakistanis are used to insurgent groups breaking from the herd to launch an attack which grabs the headlines, often under one of those spiritually inspiring names from the Islamic texts.

In most cases, they disappear from the scene just as quickly.

Shahidullah Shahid (centre) had been the TTP's main media contact

The trend started in the post-9/11 period, when elements within the militant network that were uprooted from Afghanistan started to hit targets in Pakistan.

These groups comprised fighters from the Pakistani tribal militants, the Punjabi Taliban, Central Asians, Arab fighters and militants from East Asia. Most of them gravitated towards the umbrella militant alliance called the TTP which was formed in 2007.

The earliest such group to make headlines was Harkatul Mujahideen al-Almi, which was blamed for a string of attacks in Karachi in 2002, including an assassination attempt on then President Pervez Musharraf, the bombing of the Sheraton hotel and a car bomb explosion outside the US consulate.

The group's name was similar to that of a major Kashmir-focused Punjabi Taliban group, but the addition of a suffix - al-Almi, or international - appeared to give it wider scope.

It faded away soon afterwards and has not been heard of since.

In 2004, a group calling itself Jundullah surfaced with an audacious ambush of the Karachi Corps commander. Then it took an eight-year sabbatical. Soon after it re-emerged it seemed to fall out with the TTP over who carried out the 2013 killing of nine foreign climbers on Nanga Parbat.

Jundullah claimed the credit for itself, but the TTP said a specially established unit called Jundul Hafsa had done it. Police in Karachi have blamed some recent attacks on Jundullah, but the group itself has made no comment.

As for Jundul Hafsa, it has turned out to be another one-hit wonder, at least so far.

Other short-lived groups include the Asian Tigers and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi al-Almi (LeJA), another group with a familiar name but a differentiating suffix.

Both were briefly in the news during the spring of 2010.

Apparently, the Asian Tigers claimed that they had captured two former ISI officials and a British journalist of Pakistani origin. Later, one of the ISI men was beheaded for "spying".

Some weeks after the killing, there were reports of a series of attacks in North Waziristan in which two top leaders of the Asian Tigers were said to have been gunned down by someone calling himself the chief of LeJA.

This man himself was killed along with two others by unknown gunmen two months later. The killers left a note written on a TTP letterhead accusing the dead men of kidnapping former ISI officials who "during their active service had been kind to Taliban".

Make of all that what you will - it's not straightforward.

More recently, the group calling itself Jamaat-e-Ahrar (JA) has broken away from the TTP.

It is not clear if JA is some kind of successor to a TTP-linked group called Ahrarul Hind, which represented those elements within the TTP who believe in the "final battle for India" in which, according to them, a Muslim victory was foretold by Prophet Mohammad.

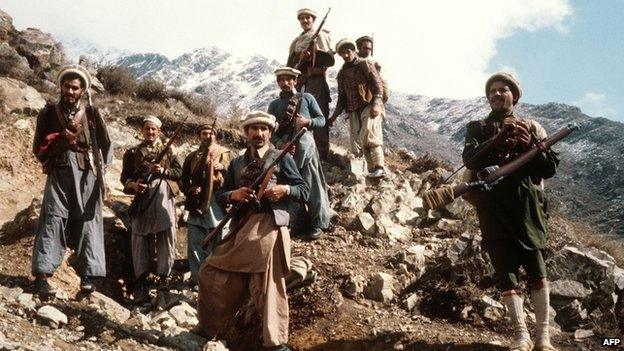

Militancy gained hold in Pakistan when resistance fighters took up arms against Soviet troops in Afghanistan

The recent launching of al-Qaeda's South Asia wing is seen by many as a continuation of this strand of militant thought.

All these groups seem to have grown from a common source - the Afghan mujahideen of the 1980s and their Arab and non-Arab allies who later morphed into al-Qaeda and the TTP.

This process was born in the shadows of a military regime that ruled Pakistan during the 1980s and hosted a seven-party alliance of Afghan mujahideen - called the Peshawar Seven - to destabilise Kabul under Soviet occupation.

The regime's ideological tilt created room for fundamentalist groups to dominate the Afghan jihad, ultimately giving rise to the Taliban movement in 1994.

By 1996, when Taliban had captured Kabul and put an end to the Afghan civil war, the Arab Wahhabi groups and Salafists who had earlier left for Africa, the Caucasus and the Balkans began to pour back into the Pakistan-Afghanistan region, thereby completing the toxic mix that has characterised local militancy in the region.

Since 9/11, the number and numerical strength of these groups has multiplied, and many of them have Pakistan - an ally in the US-led "war on terror" - near the top of their hit-list.

The Pakistani Taliban has been waging its own insurgency against the Islamabad government

Earlier this year, Pakistan's interior minister Chaudhry Nisar told parliament the main TTP movement included more than 35 groups. Later, a security policy document listed around 60 groups that successive Pakistani governments had proscribed since the late 1990s.

But there are dozens of others - all vying for limelight and funds.

Most of them have local interests. They are natives of the areas under their control, and tend to organise into regional groups to form territorial entities. They are often named after their top commander or their area of operation, such as the Mullah Nazir group, or the Mohmand Taliban.

Others have broader ideological aims.

They mostly comprise fighters from Punjab province with a background in the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) which exists to wipe out Shia Muslims. These fighters have links with al-Qaeda and its affiliates, especially the TTP and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).

They move in and out of larger groups either due to tactical or operational reasons, ideological considerations or internal group rivalries.

Many shine for brief periods, then fade away only to re-emerge in new avatars.