What have British troops achieved in Afghanistan?

- Published

Despite international aid and US-led military operations, security in Afghanistan remains fragile

As British troops end combat operations in Afghanistan, BBC Kabul correspondent David Loyn asks if the war was worth it.

There is no single score card that can rate the US-led mission in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

Four hundred and fifty-three British troops died in the war, and thousands were injured, almost all since the decision was made to go into southern Helmand province in 2006, five years after the war began.

There is no doubt that Helmand has been improved. Roads are far better, schools have opened and security has improved, at least in the most densely populated areas - the "green zone" - either side of the Helmand river.

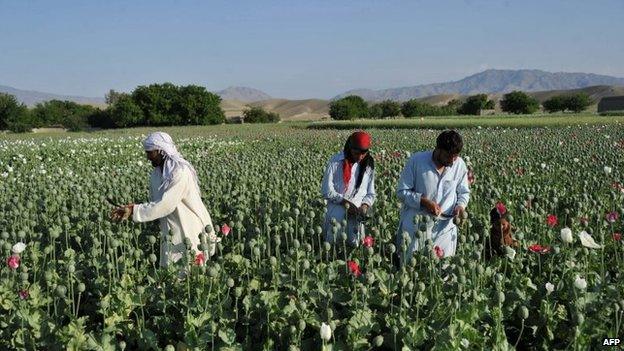

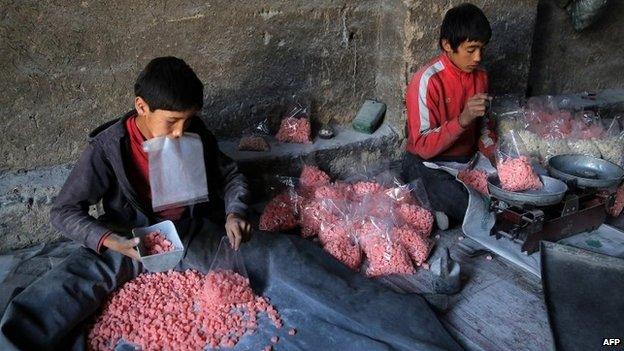

But two key aims of the operation - to defeat the Taliban and cut poppy growing - have been a failure. As British troops leave, the Taliban are stronger than ever and mounting their most determined attempt to retake the province, and poppy growing is at record levels.

Security has improved in Helmand province

And the mixed picture in Helmand is reflected nationally. On the war's original limited aims - to punish al-Qaeda for 9/11, and dislodge the Taliban from power - it can be measured as a success. But it quickly turned into a full-scale military intervention, and effort to reconstruct a nation.

'Bankrupt nation'

Already Afghanistan has sucked in more than $100bn (£62bn), mostly from the US, and mostly spent on security - more than what was spent to stabilise Europe under the Marshall Plan after World War Two, adjusted for inflation. So what did that money buy?

On the one hand, the economy has grown, millions more children are in school, universities and technical colleges are turning out high-quality graduates, there is a free media, and far better roads.

But better roads are no good if they are unsafe to drive on; women are a long way from equality; criminality and warlordism have returned to much of the countryside, particularly in the north; the country is corrupt and, in the blunt description of new President Ashraf Ghani, "bankrupt".

And this last year of the international combat mission is turning out to be the worst year for civilian casualties since 2001.

Despite efforts from the west, poppy growing is at record levels in parts of Afghanistan

In the first six months of 2014 1,564 civilians died, external and 3,289 were injured - a rise of 17% on the year before.

And the worsening intensity of fighting as international forces draw down is starkly illustrated by the fact that two-thirds more women were killed in crossfire during ground attacks.

UN investigators found that the nature of the conflict was changing, with more fighting in populated areas.

And while the overwhelming majority of civilian casualties were caused by insurgents, Afghan security forces are causing more deaths and injuries among the population they are supposed to protect than international forces did.

Afghan forces have taken very heavy casualties themselves, far higher than the international forces they replaced.

Afghan troops have sustained heavy casualties

There has also been a high desertion rate, but with no shortage of new recruits, the total for the combined Afghan forces of troops and police is now close to the planned level of 352,000.

The stability of the force has been guaranteed by the recent commitment of Nato countries to increase funding to $5.1bn a year.

But Afghanistan has also faced the unprecedented challenge of a peaceful handover of political power - and that came at the same time as the military handover.

Although peaceful in the end, the long months of negotiation over the formation of the government of national unity between the two leading presidential candidates were immensely damaging.

The country's already frail economy stagnated as capital flowed outwards, and foreign investment collapsed. Trade faltered, and government revenues, such as they were, dwindled still further.

Afghanistan's economy remains highly dependent on foreign aid

And the country's Finance Minister Omar Zakhilwal told the BBC that his successor would face enormous challenges. He cut all infrastructure spending, as the government was in effect running on empty.

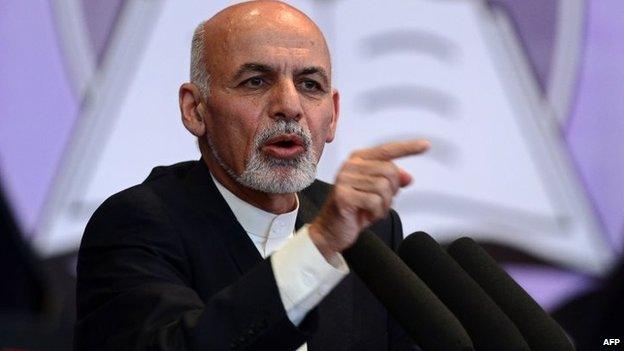

President Ghani has far more economic ability than his predecessor President Hamid Karzai, and is determined that Afghanistan should pay its way in the world.

But still, at the end of November, he will be in London, cap in hand to international donors, to see if he can secure similar pledges to increase development aid as he did for his armed forces.

He will need to persuade sceptical governments that the money will be better spent than in the past. He has sent all the right signals, reopening a fraud inquiry into the collapsed Kabul Bank in his first week in office.

By then he will have restructured his government, with a new council of ministers sitting above the cabinet to determine policy.

Ashraf Ghani has economic experience and progressive political instincts

The models in his mind for countries that have recovered from conflict and poverty are Singapore and South Korea. But the leaders in both countries had a freer hand than President Ghani, as he balances the interests of an ambitious new generation, with the fractious ex-warlords who surround the presidential palace.

He presents himself as a conservative, Koran-reading tribal elder. But he has progressive political instincts.

He likes to remind people of the fate of the last Afghan leader to try to bring European ideas into government - King Amanullah, deposed in a violent revolution in 1929.

Averting chaos?

The US Congress has already voted to halve aid to Afghanistan next year.

European donor countries, with competing demands on their sluggish economies, will want more guarantees that women's rights can be better protected, the country's flourishing opium economy can be checked, and corruption finally brought under control.

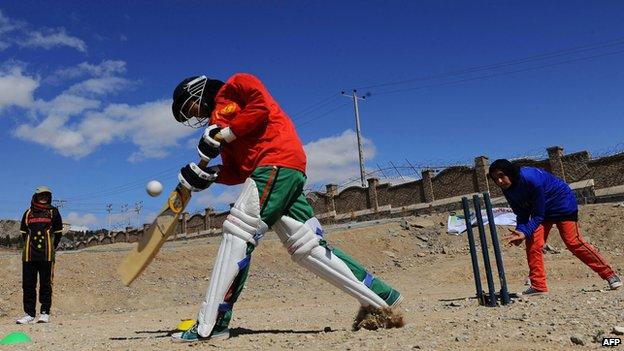

Britain's legacy includes cricket pitches, and a successful national cricket team

But Western donors also have the model of the collapse of Iraq, and will not want another crucible for Islamic State to emerge. So President Ghani will probably win the support he needs for the next couple of years at least.

The world well remembers what happens when Afghanistan is forgotten - the chaos and bloodshed of the civil war that provoked the rise of the Taliban in the mid-1990s is only the most recent example.

In Helmand, one of the British bases, in the village of Nad Ali, was inside the crumbling walls of a fort that the British had used in the first Anglo-Afghan war in the 1830s.

It is now used as a cricket pitch, in a country that is immensely proud of its new cricket prowess, and has qualified for next year's World Cup.

The legacy of Britain's involvement is complex. The national cricket team has a British head coach. And in Nad Ali, a local district council established with British support is still functioning after the troops have gone. The council leaders are grateful for the help.

But 13 years after the fall of the Taliban, international troops are not handing over a nation at peace, and for the money spent and lives lost, it could have been so much better.