Sumarti Ningsih murder: From Indonesia to Hong Kong

- Published

Sumarti Ningsih began her life in a small village deep in the countryside of central Java. At the end of her life she was found murdered and decomposing in a suitcase on a Hong Kong balcony. She was just 23 years old.

In photographs, large brown eyes peep out from underneath a dark curtain of hair. Laughing and carefree in many of the shots, Sumarti was a free-spirited young woman. She was just beginning to enjoy her life and independence.

In 2010 - aged just 19 - she became one of the thousands of Indonesian women who leave home to seek their fortune working as domestic helpers in a big city.

These women go to Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong for the high wages. They become a crucial source of financial support for their families. Eventually they return, laden with US dollars and stories of their lives abroad.

That didn't happen for Sumarti. British banker Rurik Jutting has been charged with her murder and that of another Indonesian woman, Seneng Mujiasih.

Sumarti's journey, told by people who knew her and those like her

Gandrungmangu village, Cilacap, Indonesia

It takes 10 hours to get to Cilacap by road from Indonesia's capital, Jakarta. We fly in to Yogyakarta, the closest big city, hoping the journey will be shorter - but it is still more than half a day away.

It is a journey through winding roads and scenic paddy fields. At times the mountainous terrain is dangerous and there is no telling whether a bus or a motorcycle may be coming round the next corner. This is the way everyone drives here. Anything goes.

Going deeper into the Javanese countryside, names of small towns and villages flash by: Kebumen, Gombong, Purwokerto. Deep in Indonesia's interior, the ubiquitous Indomaret convenience chain outlets are replaced by traditional family shops, a relic of the old ways. It is a world away from big city life.

There is a power blackout in the village of Gandrungmangu, where Sumarti spent her teenage years. But the lights will be back on soon. At Sumarti's home, a crowd has gathered in the darkness for a Muslim ceremony to mourn her.

Sumarti's parents - an elderly, sorrowful couple - are there.

But had she stayed here, her life in the village would have been one of daily drudgery. Everyone here wakes at dawn, so that the rituals of the day can begin. Praying, cleaning, cooking, farming - that is what her years would have been filled with.

"She had seen the money her friends made in places like Hong Kong," her mother told me. "She wasn't happy with the life here. She wanted more for us, and for herself."

It was also for her five-year-old son, Mohammad. Brought up by his grandmother, he was yet to learn of his mother's death.

"He didn't know her too well," Suratmi, Sumarti's mother, says quietly.

Sumarti's husband was a man from a nearby village who left as soon as their child was born and played no part in his upbringing.

Sumarti herself also left when the child was only 40 days old, she added.

"But she always sent money for him and told us that we must buy him whatever he wanted. She told me that he must never feel like he couldn't have what he wanted."

Not many women of Sumarti's age stay in Gandrungmangu. Locals say 80% of women here go abroad to work. They have little or no education and they have to find work to support their families. There are no jobs here. And so she did the same and became her family's lifeline.

Sumarti was generous. That much is clear from the evidence in the house. Her driving force was to improve life for her family, to make them richer. Life may be peaceful in the village but she would have been all too aware of the possibilities of a life with more material comforts.

"She helped me to build this house," her father Ahmad Kaliman says, also pointing out the washing machine and DVD player she bought for them. "Sometimes she sent us 3m rupiah ($300; £191) sometimes she sent us 6m rupiah, but she always sent us something. She was a very good girl."

Sumarti first left Gandrungmangu for Hong Kong in 2010, aged only 19, her parents told us. She went on a domestic worker's visa and sent money home every month, but returned in 2013. At that time she told her parents she was tired and that she wanted to improve her skills. There was little talk of her life as a helper or a return to domestic employment.

So she joined a DJ school in Yogyakarta. But Hong Kong life beckoned once more and she went back, this time on a tourist visa. Her parents don't appear to know how she was able to work there without the proper documentation - or perhaps they didn't ask. In any case, the money kept coming.

She returned in July for the Muslim Eid holidays. She loved coming home, her mother tells us. She would spend hours in the kitchen, cooking and baking sweet Indonesian snacks for her family. It was her favourite pastime.

But once again, it was time to return to Hong Kong. This time, though, Sumarti told her father she would be back in a few months - early November at the latest, in fact. Her tourist visa ran out on 2 November.

But just days before she was due to return home, her family learned of her death in Rurik Jutting's flat. Now her murder is all anyone in the village can talk about.

"Is it true what they say?" one of her neighbours asks me. "That she was a sex worker in Hong Kong? Is that why she was killed?" Her family is adamant that this isn't true, that Sumarti was in Hong Kong working in a cafe.

Sumarti's 15-year-old brother Mohammad refuses to believe what is being said about her.

He remembers the sister who bought him a guitar and who dressed like any other girl in the village when she was at home. But he told me of her recollections of Hong Kong life.

"She always said that in Hong Kong, people wear more revealing clothes than they do here," he told me.

"She said she felt safe there, and that nothing bad ever happened."

In Hong Kong

At the airport there's a separate line for domestic workers, most of them Indonesian, covered in their headscarves and long dresses. You can tell the new ones from those who have been here a while. The old hands are more trendily dressed with tight jeans and make-up, while the new girls huddle together in packs for comfort and support.

This is where Sumarti would have queued up on her first entrance to the city, barely out of her teens.

It is hard to imagine what it must have been like for her to come from Gandrungmangu to Hong Kong. It is too loud, too brash, too rushed. Everyone is in a hurry. The only thing that Sumarti would find familiar is how the taxi drivers drive. In that sense, here too anything goes.

One place Sumarti would have found a source of refuge and comfort on her days off while she was working as a domestic helper would have been Victoria Park, in the heart of this city. It transforms into "Kampung Java" or "Java Village" on Sundays.

More than 150,000 Indonesians live and work in Hong Kong as maids and nannies, serving the city's middle classes. On Sundays, their weekly day off, they take over the park, setting up little Indonesian enclaves in tiny corners or under bridges and street-lights.

Turn a corner from one of the main thoroughfares in Hong Kong, and all of a sudden you're surrounded by women wearing headscarves and speaking Javanese. Sumarti wouldn't have felt like an alien here. She could have asked for directions in her own language, shared an Indonesian snack with a friend on a park bench, and sent money home from one of the dozen or so Indonesian bank outlets that have set up here.

On Sundays, Indonesian domestic workers turn a part of Victoria Park into "Little Java"

But life as a domestic helper in Hong Kong isn't easy. Employers' expectations are high, and they often have little patience for workers who are trying to adjust. Rising early, looking after the children, cooking, cleaning - the daily chores that a domestic worker does to earn just US$500 a month.

That's a fortune back home, but in Hong Kong, it doesn't go very far.

Tracing Sumarti's steps after she came to Hong Kong as a domestic worker is challenging. We know that she eventually gave up that job, but after that how she stayed and where she worked is a mystery.

All that is clear is that she was working in Hong Kong illegally - a huge risk, but one Sumarti took nevertheless.

Sringatin, of the Migrant Workers' Union, says Indonesian women come to Hong Kong with "a million hopes and dreams".

Lydia (not her real name) has worked illegally in Hong Kong for the last few years. Like Sumarti, she came to Hong Kong on a domestic helper's visa - but quit to find higher-paid work. Every few weeks she has to change addresses and jobs to make sure Hong Kong's police don't find her.

Lydia knew both Sumarti and Seneng. She said they lived in an illegal workers' boarding house - an apartment carved into tiny rooms with a common kitchen and bathroom.

"I would see them in the common areas," she said. "They were very private, and kept to themselves.

"Sumarti worked as a maid for a while, but then she saw the difference between what she could make as a maid, and what she could make working illegally."

Lydia says Sumarti and Seneng were friends with another Indonesian illegal worker, who moonlighted as a sex worker in the city.

"Maybe the two girls saw the life that their friends who worked in the bars had, lots of money and fashionable clothes. It was a temptation for them, a life too hard to resist."

Lydia herself works in a bar, washing dishes and clearing tables. Sometimes, she says, men in the bar will offer to pay to have sex with her - but she says she never says yes, despite the amount of money they're willing to pay.

"It's the money that blinds you," Lydia says. "That's what makes the risk of living like this worth it. I can make double, sometimes triple what I used to make as a domestic helper - and I'm not working all the time."

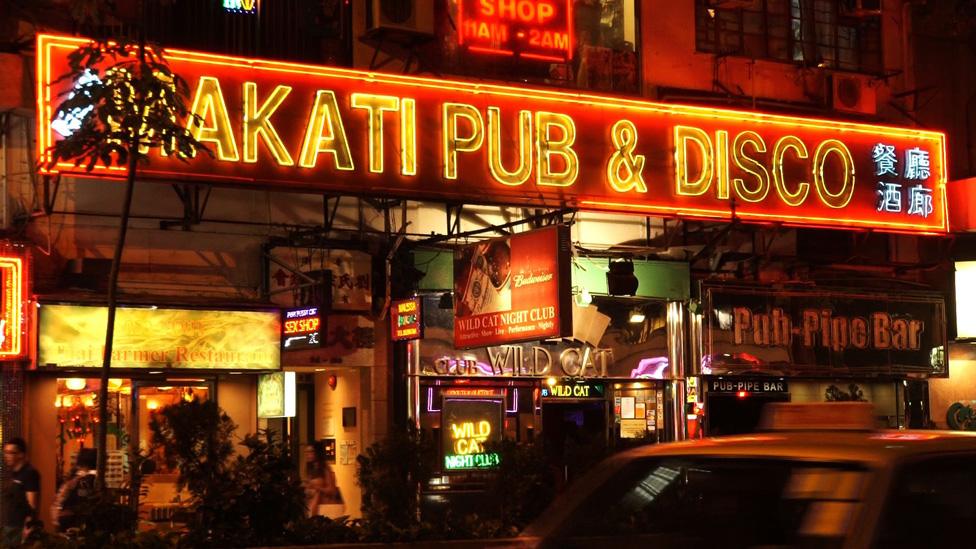

The New Makati is the club where Sumarti was last seen alive

Lydia tells us that some of the Indonesian domestic workers who overstay their visas end up in the seedy bars in Wan-Chai, Hong Kong's entertainment district.

They aren't sex workers in the official sense of the word - instead, she calls them "girls who get paid to have a good time".

She takes us to a few clubs - among them the New Makati. This is the club where Sumarti was last seen alive. In the corner, an elderly Caucasian man is groping two young Asian woman, kissing them both at the same time, and putting wads of cash in their back jeans pockets. They're obviously drunk, and don't appear to be under duress.

Dark and dank, the New Makati is full of Indonesian girls. On the dance floor there are young Indonesian women grinding and being groped by male white expats. It is a study in contrasts - the girls are wearing cheap and tight lycra dresses, while many of the men are in buttoned-up light blue Oxford shirts, looking like they've just stepped out of a Gap store.

Nita (not her real name) is a young Indonesian woman who arrived in Hong Kong recently to work as a domestic helper. On her first Sunday off she came to the New Makati with her friends to hang out. Since then, she's been back every week.

At some point in the days before her body was found, Sumarti entered this building, an affluent block of flats in Wan Chai

"I like to come here, to talk, to dance, to have fun," she tells us. "You know, it is easy to "mancing" here - you never know who you might find in the New Makati."

Mancing in Indonesian means to go fishing - a euphemism for hooking a big catch - a "bule" (white) boyfriend, a passport out of poverty. Workers tell me this is the goal of some Indonesian women who end up in Wan Chai.

"All they want is a boyfriend who can look after them, someone to make life easy and pay for things. In return they have fun with them. Hong Kong is expensive and it is a hard place to live," Nita says.

We are unceremoniously hurried out of New Makati, after we try to take some photos. The bar owners don't want any of this documented. Neither do the girls. Prostitution isn't illegal in Hong Kong but it's certainly not something the girls want to talk about.

And of course it is only some of the workers who take this route. But they all come to Hong Kong wanting to better their lives.

Police, pictured searching Mr Jutting's home, found Sumarti's body in a suitcase

"These migrant workers from Indonesia come to Hong Kong with a million hopes and dreams," says Sringatin, the deputy head of Indonesia's Migrant Workers' Association in Hong Kong. "They want to provide a better future for their families. These dreams force them to do whatever it takes to show everyone at home they've succeeded. Failure is not an option."

Back in the village

A few days after her death, Sumarti's body was flown back to Jakarta and then driven to her village. She was buried in her village cemetery. The early-morning ceremony was attended by her friends, family and dozens of neighbours.

Sumarti's repatriated body was buried in her home village

Her son has now been told about his mother's death, but he doesn't understand what that means - that she's never coming home.

He plays with his friends in the village fields. It is an innocent, idyllic scene. The boys pick fruit from the trees, racing each other to get up the tree trunks first. In a corner the girls are busy giggling and playing the Indonesian version of hopscotch. Sumarti would have played under the shade of these trees too, when she was little.

The girls' faces are fresh and untouched by the indulgences and cynicisms of city life. When you ask some of them what they'd like to be when they're older, the answers are refreshingly optimistic - a teacher, a doctor, a nurse.

No one says their ambition is to become a domestic worker. But the reality is that's what the future likely holds for most of these girls. As long as there are no jobs, young women will leave Indonesia's villages to find work.

Sometimes, though, the price they pay may be too high.