Afghanistan: Can pomegranates power the economy?

- Published

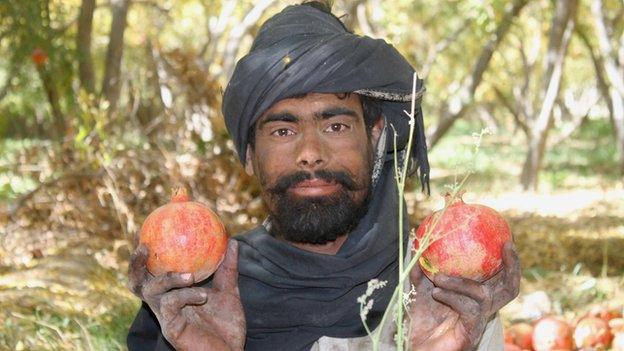

Farmers face a tough choice between lucrative opium poppies and legal crops such as pomegranates

As delegates gather in London for a conference on Afghanistan, the prospects for reducing the reliance on foreign aid are increasingly focused on two sectors of the economy: agriculture and hydrocarbons.

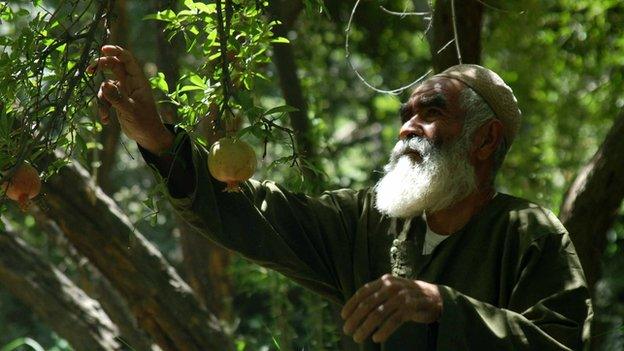

Harvest time is coming to an end in the fruit orchards of Kandahar, a province now more associated with the Taliban than its famous pomegranates.

Amid shouts of "Ya Allah! Ya Allah!" fruit pickers are urging care as they pass the valuable crop from the tree tops to catchers on the ground.

The weather is still mild and ideal to let the fruit sweeten. Packed in boxes or jute sacks, the fruit make its way to markets and warehouses, some goes to Pakistan and the Middle East.

But for Afghanistan to profit from one of its key crops, it needs to reach more profitable markets in Europe and beyond.

Afghan pomegranates are among the best in the world, according to experts

To make pomegranates pay, Afghan exporters need to tap European markets

Learning curve

In a factory in southern England, cartons of pomegranate juice are rolling off the production line.

The Pomegreat juice company buys quality pomegranate concentrate from all over the world and now has its sights set on Afghanistan.

"Pomegranates from Afghanistan are amongst the best in the world," says its boss Adam Pritchard. "But the logistical challenges are also amongst some of the most difficult."

Could pomegranates replace poppies in Afghanistan's agriculture industry?

At this week's London Conference on Afghanistan, Mr Pritchard has signed a multimillion pound supply agreement with the Kabul-based Omaid Bahar Fruit Processing Company to buy 1,000 tonnes of pomegranate concentrate.

It could prove a blueprint for Afghan agriculture in the years to come if all goes to plan.

Pomegranate juice is growing in popularity in the UK

Adam Pritchard has signed a deal with Afghan suppliers

Plenty of challenges

In an office in central Kabul, Najlla Habibiyar, head of Afghanistan's Export Promotion Agency, is realistic about the extent of the challenge facing Mr Pritchard and his Afghan partners.

She is only too aware of how tough it is for Afghan farmers to make a living from pomegranates, in contrast to the illegal mainstay - opium.

Pomegranates need "work, time and a good market", she says. "But with poppies, farmers know they'll get paid, even if their crops get eradicated. It's less hassle."

Opium production was up 17% this year - as poor security further dented efforts to stamp out poppy growing.

Pomegranate production is also on the rise. But while poppy farmers can expect the buyers to come to them, pomegranate growers face big obstacles getting their fruit to market.

"The main challenges are to have proper facilities for cold storage, processing and packaging", says Najlla Habibyar. "And unfortunately we don't have an internationally recognised body to do the final quality checks and certify the product."

When Pomegreat first looked at buying juice concentrate from Kabul, these complications meant the final product was just too expensive.

But Adam Pritchard hopes things will be different now.

"We're trying to work with the manufacturing facility to help them develop a process which allows their product to become more commercially viable and to compete in the world market," he says.

Experts say the energy sector is a more viable long-term basis for prosperity

Oiling the economy

In northern Afghanistan, foreign investors are also working with local companies to kickstart the economy.

In this case, the end product is oil.

In the basin of the Amu Darya, one of the region's great rivers, the Kashkari oil field is one of three being developed by China's National Petroleum Company in partnership with Afghanistan's Watan Group.

The 25-year profit-sharing deal was signed in 2011. Three years on, there are brand-new looking installations on show, but progress is slow.

There are thought to be around 80 million barrels of oil in these fields.

It is not much in global terms, but it would be enough to fuel the local economy if the oil could be exploited and processed more quickly.

Daily production so far is just a fifth of what was expected, according to the mines ministry.

There is no processing capacity on site and the crude oil has to be transported to the nearest refinery in Hairatan, a dangerous four-hour drive.

Afghanistan is trying to exploit several oil fields

Lal, one of the lorry drivers who does the trip regularly, says he and his colleagues have no choice.

"We are paid just $200 to take this route," he says. "When we are attacked, it's for $200. If we get wounded, we get just $50 compensation."

Lal is one of a few hundred people benefiting from the employment opportunities oil exploration has brought.

The Chinese-Afghan consortium is also training local engineers and technicians as part of the production agreement.

But apart from that the local economy has yet to feel real benefits in terms of cheaper petrol and energy supplies.

Even so, Rafiq Siddiqui from the Mines and Petroleum Ministry says oil, gas and Afghanistan's other commodities are the way ahead.

"With the plans the national unity government has, and with good management, we believe that the way to economic stability is through natural resources. And that's not far away," he says.

Experts agree that mining could be the game-changer for the Afghan economy in the long run.

In the meantime agriculture, the sector that employs most Afghans, will have to plug the gap.

Adam Pritchard thinks top-quality produce like pomegranates can help to fulfil that need.

"If Afghanistan is to stand on its own two feet, it can't rely on subsidies and charity," he says.

"The English apple is synonymous with England. We process it and make juice out of it. There's no difference with pomegranates in Afghanistan, and I have no doubt that in time it will be a decent industry for the country."