Xinjiang: Has China's crackdown on 'terrorism' worked?

- Published

Intimidation makes reporting in China's Xinjiang region difficult

"Kashgar is not stable."

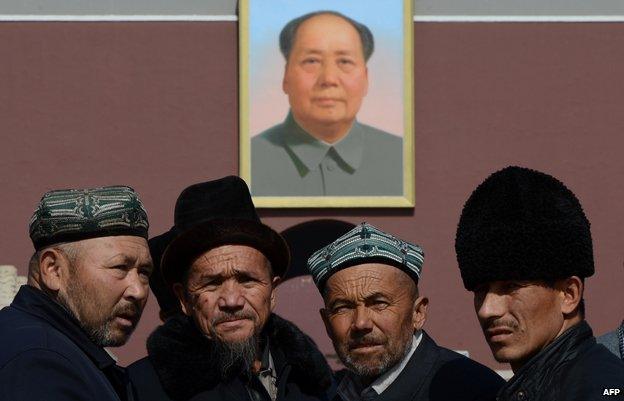

The words of a paramilitary police officer as he marched past me under the statue of Chairman Mao in China's westernmost city.

It was the answer to my question: "Why are there so many armoured trucks, so many armed officers, so many police dogs?"

A history scarred by civil war and foreign invasion makes many Chinese citizens hanker for strong central government.

But for security, they pay a high price in civil liberties.

Especially in border areas like this which are so different from mainstream China and where the pressure to show loyalty is correspondingly immense.

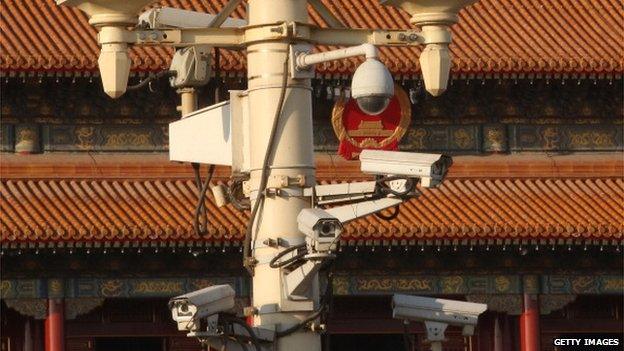

The government is watching every citizen.

The BBC's China Editor Carrie Gracie recently paid a visit to Kashgar city in the Xinjiang region

'Triple evil'

I was in Kashgar to tackle one of the hardest China stories to cover.

The story, according to the Chinese government, is "a triple evil", a mix of religious extremism, separatism and terrorism.

In May, it announced a year-long security campaign after a shocking series of attacks made the state look weak.

Exiles and human rights groups say the story is that the state itself is making matters worse, and the violence is fuelled by repression against a religious and ethnic minority, China's Muslim Uighurs.

Uighurs and Xinjiang

Uighur culture leans more towards Central Asia than China

Uighurs are ethnically Turkic Muslims and make up about 45% of the region's population; 40% are Han Chinese

China re-established control in 1949 after crushing the short-lived state of East Turkestan

Since then, there has been large-scale immigration of Han Chinese

Uighurs say they have been economically marginalised and fear their traditional culture is being eroded

The far western region of Xinjiang officially became part of Communist China in 1949

Xinjiang is China's largest administrative region and borders eight countries

Chinese or Muslim first?

I wanted to see the counter-terror crackdown at first hand, to hear from Uighurs about the religious restrictions they now face, and to make my own assessment of how the two relate.

The mission was made much harder by government surveillance both of me as a foreign journalist and of the people I was trying to talk to.

Kashgar is the last stop before Pakistan, closer to Baghdad than it is to Beijing. It's at the far western edge of the troubled province of Xinjiang, home to 10 million Uighurs.

China doesn't trust the loyalty of these citizens. It worries about whether they are Chinese first or Muslim first.

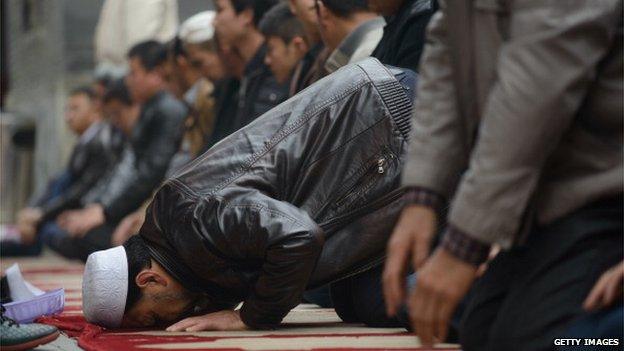

Which is why alongside the security push, the past six months have seen sweeping restrictions on religious expression.

The further west and further south you go in Xinjiang, the more troubled the past and the present.

This land has seen empires come and go.

In the 20th Century, even the Russians dabbled here from just over the border in Soviet Central Asia, supporting Uighur claims for an independent state of East Turkestan.

But the Chinese Communist Party sees Xinjiang as an integral part of the People's Republic of China and teaches its citizens that the determination to hold onto it is not about mineral wealth or the geopolitics of Central Asia but a sacred trust for Chinese patriots.

China continues to step up the security presence in many key Xinjiang towns and cities

Just two days before I arrived, the area had seen another violent attack in which 15 people had died.

As so often, the incident involved a vehicle ploughing into a crowd and multiple attackers with knives and homemade explosives who were then shot dead by police.

At least 200 people have now died in clashes related to Xinjiang over the past six months and perhaps half of those killed are the attackers themselves.

So what is causing young Uighur men to commit acts of violence which so often end in their own deaths?

The Chinese government says they are being poisoned by the holy war propaganda of militant Islam, propaganda flooding across the border from Pakistan and Afghanistan on DVDs, mobile phones and internet.

As part of the year-long counter-terrorism campaign, Chinese police said they have confiscated thousands of videos inciting terrorism and blocked online materials teaching terrorist techniques.

Security surveillance or paranoia: Will China's measures successfully counter terrorism fears?

Discouraging religion

As I travelled between Kashgar and a neighbouring city on a public bus, I witnessed young Uighur men obediently filing off at police checkpoints so that their phones could be checked for religious materials.

"Nothing religious at all. You can have nothing at all on there," one man told me as we watched another climb back on the bus and reassembled his phone.

"The government wants to discourage religion. No official is allowed to pray in a mosque. And no one under the age of 18 is allowed in. No children."

A Uighur police officer told me the same thing. "I am a practising Muslim but I can't pray at the mosque."

When I asked how he felt about this, he looked nervously around him and pulled a wry expression.

His caution was understandable. It is dangerous to complain about any government policies in Xinjiang.

To the state, any criticism is construed as sympathy with the "three evils" of religious extremism, separatism and terrorism.

Chinese authorities insist that Xinjiang is now on the radar of international jihdism

The government insists its terror problem is a foreign import, that Xinjiang is now on the radar of international jihad.

It says the internet is poisoning young Uighur minds with off the shelf visions of martyrdom and a sense of belonging to a bigger mission.

Certainly a suicide attack on Tiananmen Square a year ago which killed and maimed many innocent tourists was accompanied by a video in which the attackers pledged holy war.

Earlier this year, Islamic State (IS) leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi criticised Beijing's policies in Xinjiang and asked all Chinese Muslims to pledge allegiance to him instead.

An English-language magazine released by al-Qaeda described Xinjiang as an occupied Muslim land to be recovered into the Caliphate.

China has been criticised for failing to distinguish between religious extremists and peaceful Muslims

But China makes no attempt to distinguish between religious extremists who may be prepared to carry out or condone acts of terror, and those in Xinjiang with a religious, political or economic grievance which they attempt to resolve peacefully.

One of the things I tried to do in Xinjiang was to visit the home village of the Tiananmen Square attackers.

I'd read reports that the beginning of their alienation was not jihadist videos but rage against the state for demolishing parts of their mosque. I wanted to understand more about their psychological journey from law-abiding Chinese citizens to vengeful martyrs.

The ethnic Uighur population used to be the majority in China's Xinjiang region

Chinese officials blamed the attack at Tiananmen Square on separatists from Xinjiang

'Spies everywhere'

Despite several attempts to reach the village, I was not allowed in. Whether by Uighur citizens or foreign journalists, the government is simply unwilling to tolerate public discussion of the role of religious, political and economic grievances in creating its Xinjiang problem.

But I did see evidence that those grievances are mounting.

I talked to men who complained that they were no longer allowed to grow a beard, and to women who are no longer allowed to wear a veil.

A Uighur guard at a Kashgar hospital told me women who insisted on covering their face would not be admitted for medical treatment.

And a Uighur government official told me he hated his job because he could not speak any truth and there were "spies everywhere".

Uighurs fear that they have been economically marginalised

There are also rumbling economic grievances.

Uighurs are now a minority in their own homeland and some complained to me that they face discrimination when it comes to jobs.

One Uighur boss of a construction company conceded: "The top jobs in my company all go to Han Chinese. They have the education and we Uighurs simply don't."

And a Han Chinese was even more disparaging.

"No one would employ Uighur workers if they had a Han alternative. The Uighurs are lazy and incompetent. It will cost you three times as much to get the job done and it still won't be done to the same standard."

Even in their traditional crafts, Uighur livelihoods are under threat.

A metal worker crouched over his anvil told me: "I've been doing this for 20 years. It takes me two weeks to make a fine teapot. But now the machine made goods from China are flooding in. It's hard to make a living."

Prominent Uighur academic Ilham Tohti was found guilty of 'separatism' by a Chinese court this year

Over the past 30 years, Chinese policy makers have assumed that economic growth in Xinjiang would stifle dissent but in some ways, modernisation seems to have made Uighur marginalisation worse.

President Xi visited Xinjiang just before the counter-terror crackdown and promised more economic opportunity, saying the Uighur and Han peoples must be "as close as the seeds of the pomegranate".

But the President also urged "decisive action… to resolutely suppress the terrorists' rampant momentum".

And in the short term, this action is more visible than the other.

China continues to grapple with the 'rampant momentum' of a terrorist threat in Xinjiang

After a brief visit to Xinjiang, my provisional assessment is that despite the police officer telling me "Kashgar was not stable", the overall security situation in the province was under control and there was no meaningful challenge from militant Islam.

I saw a lot of security. On key roads, in airports, on city streets.

But I did not see the level of police tension or preparedness that would suggest China was grappling with the "rampant momentum" of a serious terrorist threat.

What I did see instead was a Uighur community under intense surveillance, a community whose already very limited freedoms of speech, religion and movement are now being shrunk further.

Without any legitimate space in which to vent about this, the grim probability is that violence will go on, with some young Uighurs enraged and desperate enough to choose death in a hail of bullets rather than what they see as a life of subjugation.