Bold Modi tackles Muslim Kashmir head on

- Published

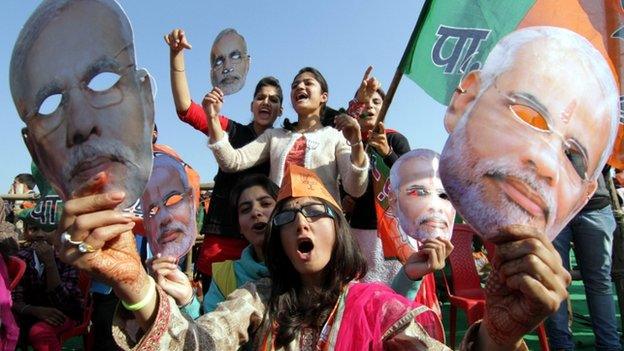

Narendra Modi has made repeated visits to Kashmir

A Hindu nationalist prime minister of India addressing a big election rally in Muslim majority Kashmir, the most troubled and disaffected corner of his nation.

That's the bold political move, external Narendra Modi made on Monday.

It's a sign of his style - highly engaged, politically courageous, much more pragmatic than his detractors expected - but offering few concessions on what he sees as the issues fundamental to rebuilding India's national confidence and standing.

In his six months in office, Modi has often startled and surprised observers, and shown a boldness rarely evident at the top level of Indian politics in recent years.

He has established a dominance of the country's political landscape arguably unparalleled since the death of Indira Gandhi 30 years ago.

Taking to the podium at a cricket stadium in the Kashmiri capital, Srinagar, Mr Modi sported a pheran, the woollen cape-like garment which is as typically Kashmiri as you can get. Much more of a political statement than a fashion statement.

And a move that attracted approving newspaper headline, externals in Kashmir even before the crowds started gathering.

It was many years, he declared, since an Indian national leader had addressed an election rally in the main part of the historic Sher-e-Kashmir stadium.

The stadium's name translates as Lion of Kashmir - the title given to the iconic Kashmiri nationalist leader from the 1940s to his death in 1982, Sheikh Abdullah.

At times in his long political career, Sheikh Abdullah supported Indian rule - at times, he called for self-determination for Kashmir and spent many years in Indian jails as a result.

The current state assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir are the occasion for the prime minister's visit, and he pointed to the high turnout in early rounds of voting as a sign that Kashmiris had rejected violence.

Concerns acknowledged

His critics complained that Srinagar was in lock-down, and the internet shut down, while the prime minister was in town.

Many in Kashmir want to leave India

And the state's chief minister, Omar Abdullah - the grandson of Sheikh Abdullah - commented acidly that trainloads of supporters of Mr Modi's BJP had been brought in for the event from Hindu-majority Jammu. "Why not just have the rally there?" he tweeted.

But the point of Mr Modi's visit was precisely to be heard and seen at the centre of Kashmiri culture and history - sticking narrowly to his political heartland is not his style

Mr Modi promised his audience in Srinagar that he would deliver jobs, prosperity and an end to corruption. He praised Indian soldiers for safeguarding democracy, but also acknowledged Kashmiri concerns about trigger-happy troops.

For the first time in 30 years, he declared, the army had acknowledged its error in the recent killing of two young Kashmiris, and action had been taken against those responsible.

"It is proof of my intentions," he declared. "I have come to give you justice."

Tens of thousands of Kashmiris, and Indian soldiers and police, have been killed during decades of separatist insurgency.

Relations with Pakistan - seen by many Indians as supporters or indeed instigators of separatist violence - remain tense, and there has been an increase in incidents on the nearby border and ceasefire line.

Overall though, the level of violence in Kashmir has fallen sharply in recent years.

The Indian authorities believe that there may be not many more than 100 armed separatists active in the Kashmir valley.

Yet among many young Kashmiris, there remains deep disaffection with Indian rule and distrust in mainstream politics.

Separatist campaign

When Narendra Modi addresses Kashmiris, he knows that few are supporters of his party and many don't want to be part of the nation he leads.

The BJP wants still greater integration of Kashmir with the rest of India - and in his speech, the prime minister gave no indication of a new approach to demands from many Kashmiris for autonomy or for separation from India.

"Narendra Modi didn't reach out to the people of Kashmir politically", says Shuja'at Bukhari, editor of the Rising Kashmir newspaper, "and the basic issue of alienation remains".

Muslim marginalisation:

India's general elections earlier this year that gave the BJP a landslide victory also served to underline the political marginalisation of the country's Muslims.

Although the BJP has had Muslim members of Parliament in the past, there are currently no Muslims in BJP ranks in the lower house.

Muslims make up one-in-seven of India's population - but just one-in-27 of its MPs in the Lok Sabha (India's equivalent of the House of Commons.)

Yet fears voiced by Narendra Modi's detractors that given the chance, he would erode the country's democracy, chip away at the secularism on which independent India has been based, and further diminish the standing of Muslims and other religious minorities have not been borne out.

But he keeps on coming back to Kashmir.

The prime minister has had support at his Kashmir rallies

He has visited more often than any recent prime minister - and in October chose to spend the most widely celebrated Hindu festival of Diwali in Kashmir, where (Indian soldiers apart) Hindus now make up a tiny proportion of the population.

It was, he said, to show sympathy for those affected by floods which had devastated Srinagar the previous month.

"I have come to share your pain and anguish," Modi told his audience in Srinagar on Monday.

Not all will take that statement at face value.

But even those Kashmiris who kept away from the Sher-e-Kashmir stadium may take comfort in an Indian leader who comes to Kashmir rather than ignores it.

Andrew Whitehead, editor of BBC World Service News, is a former BBC Delhi correspondent and the author of a book about the origins of the Kashmir conflict.

- Published23 October 2014