Could Aleppo plan cut Syrian bloodshed?

- Published

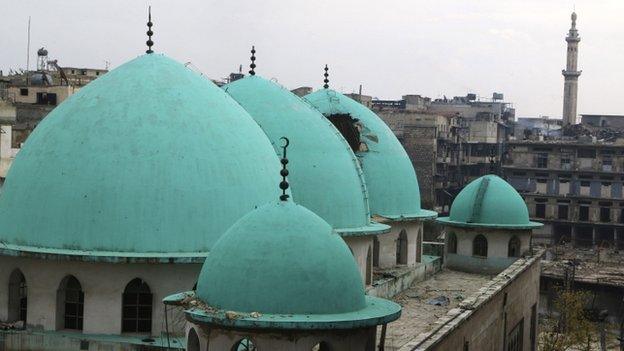

Aleppo - Syria's second-largest city - has suffered massive damage after years of war

Four years into a punishing war, the West is still in search of a Syria strategy.

Now the EU is trying to find its own voice on this deepening crisis as its foreign ministers sit down with their new foreign policy chief in Brussels.

"Syria is not a crisis that can be solved from Brussels alone but we have to fully play our role," the EU's Federico Mogherini told me in an interview in London.

"We want to empower more actors and we believe the UN is the right actor."

Ms Mogherini's predecessor Baroness Catherine Ashton took a backseat to other world powers on the Syria file as she focused on other crises.

On Sunday, Europe's foreign ministers and top officials met the UN's Syria Envoy Staffan de Mistura to discuss his ambitious new plan: a local "freeze" in hostilities which would boldly begin in the embattled city of Aleppo.

One European official attending this week's meetings told me they want to explore ways to support the UN's initiative which involves containing warring sides in their current positions to de-escalate the violence.

The goal is also to create a secure place to provide aid to a long-suffering people, and some political space, however small, to rupture a long deadlocked political process.

When I asked a senior UN advisor whether he thought this latest idea from the third UN Envoy in four years would work, he replied with barely concealed frustration: "It's the only idea!"

But that still leaves the question: could it possibly work?

Why stop?

One of the biggest questions is why the Syrian military would call a halt in Aleppo when its forces, reportedly bolstered by fighters from Iran, and Lebanon, are now closing in on the last rebel-held areas.

Reports on Sunday said they are pushing closer to a hill controlling the last vital supply line that runs from the Turkish border into opposition areas in the divided city.

On his trip to Damascus in November, the UN envoy met a barrage of criticism from President Assad's top aides, who have long dismissed all opposition forces as "terrorists."

But President Assad then called the plan "an initiative worth studying."

Cautious optimists call it a good sign.

Aleppo is divided between regime forces in the west and rebel-held districts in the east

Critics see a president merely angling to take a political high ground before the opposition rejects the plan and gives him a green light to finish his punishing assault on Aleppo's remaining rebel strongholds.

Mr de Mistura has just completed a trip to southern Turkey where he met rebel commanders to try to marshal their support.

It's no easy task. On last count there are now 18 opposition forces fighting in and around Aleppo ranging from the Islamic State (IS) group, estimated to be only 22km (14 miles) from the edge of the city, to more moderate Western-backed groups in its eastern neighbourhoods.

Some groups, drained of resources and resolve, are known to be anxious to take advantage of this possible pause. Others, including the al-Qaeda linked Nusra Front, are vowing to fight on.

Mr de Mistura's gamble is that the new threat to all sides posed by Islamic State presents a danger as well as an opportunity

"No-one is actually winning, everyone is losing," he said when I interviewed him last month in Syria.

"We have to start somewhere before the whole country looks like this," he insisted as he gestured to the blackened ruins of the Old City of Homs behind us.

But many ask how a local deal fits with a wider strategy to resolve the stubborn political crisis tearing Syria apart.

Risk of backfiring

The UN's hope is that progress in the iconic city of Aleppo, which would have to draw in many Syrian actors as well as their quarrelling allies, could help provide some rare momentum on the political front.

There is a risk it could do the opposite.

"Who will guarantee this plan and ensure the Syrian military doesn't redeploy its forces to another front?" one European diplomat asked.

A senior Western official also admitted the freeze could be invaluable to the US-led international coalition which is now mainly focusing on air raids targeting IS positions in Syria and Iraq.

"It could help relieve the pressure on Aleppo," he conceded.

President Assad has said the Aleppo initiative is "worth studying"

A defeat for Western-backed rebels in one of their last remaining strongholds would be a major setback to the West including the US, which is under mounting criticism in the region for its resistance to much more active engagement.

Mr de Mistura calls his plan "the only game in town" but such are the complexities and contradictions of Syria's war that many games are being played all at once on one dangerous playing field.

Russia has been hosting meetings to test the waters for another possible round of high level negotiations.

Some call it Geneva 3, or even Moscow 1. But expectations are at rock bottom after the government and the opposition made no headway in the first rounds.

Arab states, who continue to arm different sides in the deeply divided opposition, are now coming up with competing peace plans. Several countries, including the United Arab Emirates and Jordan, went to Moscow to present their own carefully crafted formulas, only to discover others were doing the same.

And Turkey believes it is at last making progress on military plans with some of its allies for what's being called a buffer zone or "safe areas" along its border, inside Syria.

The effort comes after President Obama again made it absolutely clear to Turkish leaders that their long standing demand for a "no fly zone" simply would not fly.

So Europe now prepares to move onto this roughest of terrain armed, most of all, with a plea that something has to be done or, at least, tried.

- Published14 December 2014