Pakistan's snow leopards: Both feared and sought

- Published

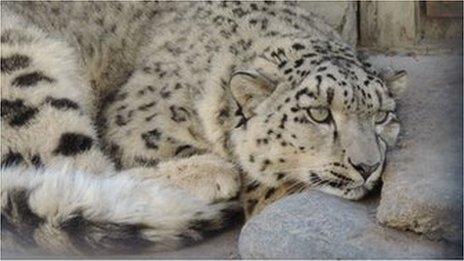

Snow leopards are both a boon and a threat for local communities

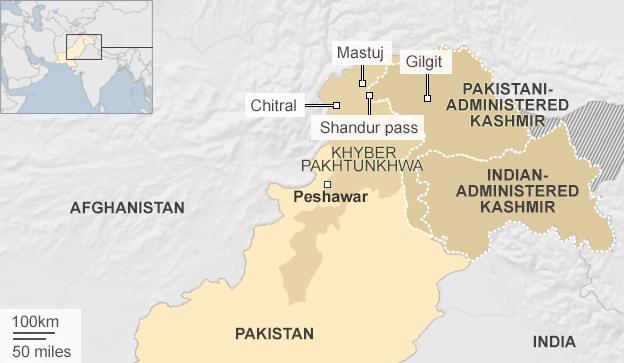

Snow leopards have been forced to the edge of extinction by hunting and human encroachment and are now one of the world's most endangered animals. In the far north of Pakistan, locals have long feared them but find themselves now relying on money that saving snow leopards brings in. What is it like living alongside a ferocious predator? M Ilyas Khan finds out.

Retired teacher Hasil Murad Khan is hurrying to report "a matter of grave concern" to the police

"The boys down in Ramaan have seen a snow leopard, and I have come to report it before there's any trouble," he says.

Mr Khan is also head of the co-operative in Ramaan, a remote mountain village in Chitral district.

"The sooner I report it to my high-ups, the sooner they'll inform the relevant authorities for action," he explains. Within the hour, a pair of policemen are expected to set out on patrol around the village, joined by wildlife department Ranger Yaqoob Shah and a couple of volunteers.

The authorities do not normally react with such speed, particularly somewhere so remote, but snow leopard conservation is important to both communities and officials here.

Cash incentives

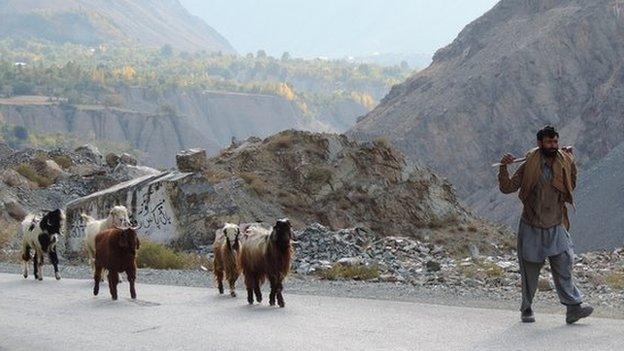

Substantial investment programmes are in place to help preserve these rare animals which, though rare and beautiful, present a serious threat to livestock.

Slowed-down version of Imtiaz Ahmad's footage of the snow leopard

"These are pastoral communities with heavy dependence on livestock, and a carnivore's presence scares them," said Dr Ali Nawaz of Quaid-e-Azam University who supervises an internationally-funded snow leopard programme in Pakistan.

"The problem is compounded by the fact that all carnivores are protected by law, and nearly all the communities in the snow leopard range have agreements with the government and international donors to protect those carnivores."

In return, these communities get substantial investment in livelihood and habitat improvement projects which may be reduced if one of their members is found harming the area's wildlife.

A hairy encounter

Snow leopards are elusive - but a number have been filmed by remote camera stations

"It happened way back in the past, maybe 15 years ago. It was my turn to herd the village flock. I led them up the Shali Gol gorge.

There was some commotion in the herd behind me, and the dog started to bark. I turned around and saw a snow leopard grab a goat by the throat and take off towards a ridge.

I ran after it with an axe in my hand. The snow leopard could not run fast because it was carrying the goat between its jaws and forelegs and had to jump at each step.

I caught up with it from behind and swung my axe, bruising it slightly near the tail. But just then it took a leap across a stream that was flowing down the slope. It cleared to the other side but the goat fell in the gushing water, its blood turning the water red.

As I looked up, the snow leopard turned around to face me, and the anger inside it seemed to boil over so hard and the hair on its face and chest swelled to such a bulge I could no more see its shoulders or hips.

The next thing I remember, I was running as fast as I could, and there was no axe in my hand. To my knowledge, never before has a snow leopard spared a living thing that wanted to run away from it."

Mohammad Khanis, 55, Shali village in Chitral

But what has been even more lucrative for the local communities is a trophy hunting programme started by the Pakistani government in the 1990s.

Under this system, communities that agree to enforce the ban on poaching of carnivorous predators, including snow leopards, are awarded lucrative annual permits which they can sell to foreign hunters to hunt wild goats - which are otherwise included in the hunting ban.

The snow leopards' movements are closely monitored

Locals' goats are at risk from snow leopards...

... as are other livestock

In a good year, village co-operatives across Pakistan's snow leopard range, which is spread over more than 80,000 sq.km (31,000 square miles) have raised $700,000-$800,000 from trophy hunting permits.

Co-operatives that can regulate their livestock grazing patterns more efficiently than others have done better because they tend to attract a larger population of wild goats, and therefore more hunting permits.

This also benefits the snow leopards, which feed on the wild goats.

"The lesser the grazing pressure on alpine pastures, the more the wild goats will prosper, and the greater will be the chances of survival of snow leopards that feed on those goats," says Shafiqullah Khan, field officer in Chitral for the World Wildlife Fund.

Snow leopards

Some 4,000 to 6,000 worldwide; between 200 and 400 in Pakistan

Native to the mountains of Central and South Asia, their range stretches over more than 80,000 sq km (31,000 square miles) in Pakistan's extreme north

Mostly feed on wild animals, but livestock is also fair game

Retaliatory killings by farmers are not uncommon but are rarely reported

But despite all these efforts and interventions, livestock still remains central to an economy which has not yet moved beyond the subsistence level.

And this entails a continuing conflict between humans and wild predators - every year there are reports of livestock damaged by snow leopards, and of snow leopards being shot or poisoned to death by angry farmers.

"Retaliatory killings are a knee-jerk reaction, and they continue to happen because even the community, which may disapprove of it, tries to cover it up to avoid trouble with the authorities and the donors," said Dr Nawaz.

This is compounded by a changing environment.

"Human population in Pakistan's snow leopard range has increased by four times since the partition of India in 1947, and livestock levels have gone up by 40% to 60%," he said.

Hasil Murad Khan was in a hurry to report the sighting

The duck pond where his son spotted a snow leopard

"By comparison, the population of wild mountain goats has decreased by at least 50%, and nearly half of their ranges have been lost to livestock and farming."

Pakistan is still home to between 200 and 400 snow leopards, Dr Nawaz says, but sustaining this population will require a massive effort of the international community at what he calls the "landscape level".

In this setting, the policemen and the wildlife rangers posted in remote valleys act as a stabilising factor in relations between communities and conservationists.

Back in Ramaan village, Hasil Murad Khan has given officials a detailed description to work from:

"My son was at our duck pond and saw it himself. He told me it had small ears, a dome-shaped face and a tail that looked like a slightly curved hosepipe."

Local knowledge

But such details are only an official formality for communities living in the range area. They know their foxes from wolves, and their lynxes from snow leopards.

They even know the routes various animals travel.

"It probably descended to an uninhabited pasture high on that hill over there, as many of them normally do during the winter," said Mr Khan.

"Finding no prey there, it probably took the Ramaan Gologhe gorge to descend to the river. A couple of boys who were fishing there threw rocks at it, so it left the riverbank and jumped into our duck pond, waded to the far end and disappeared into the trees behind."

An hour's drive further to the east, up the last climb to the 12,500-foot Shandur Pass, we come across scores of yaks spread wide across an expansive pasture of lush grass, grazing under a chilly afternoon sun.

And just a few feline leaps over a ridge and down a cliff off to the west, a snow leopard is on the prowl.

- Published19 February 2015

- Published8 December 2014

- Published26 April 2014