Nepal's hamstrung constitution: Why the wait?

- Published

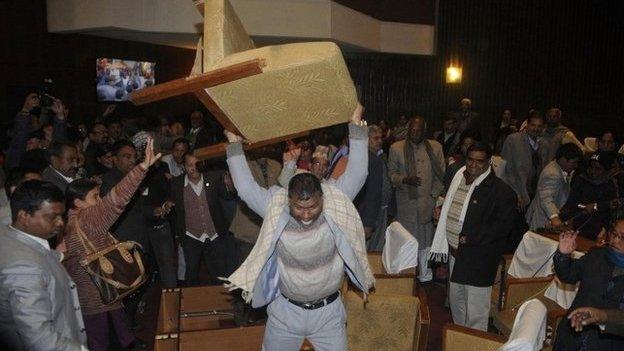

Tensions are running high in the capital Kathmandu

Nepal's wait for a new constitution has been long and painful, and followed a decade of bloody civil war.

Under the country's former monarchy the constitution was written by commissions approved by the king - but Maoist rebels fought an insurgency to overthrow the monarchy and install a new democratic republic.

A fresh constitution would be another step in Nepal's democratisation, which began in 2006 with the signing of a historic peace agreement between the Maoists and the then government.

But since then hopes of progress have stalled as political parties failed to agree over such key issues as the names and number of proposed states, forms of governance and electoral and judicial systems.

Repeated deadlines for a new constitution have been missed and several governments have come and gone.

Deadline looming

Thousands of police have been deployed ahead of the expected vote on the draft constitution

The first elections after the 2006 peace agreement catapulted the Maoist former rebels, now known as the United Communist Party of Nepal - Maoist (UCPN-Maoist), to power. They became the largest party ahead of the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal - United Marxist and Leninist (CPN-UML), which were relegated to the second and third largest elected political forces respectively. The Madhesi Janadhikar Forum (MJF) also emerged as a remarkable force from the Madhesi plains of southern Nepal bordering India.

But petty politics meant this first Constituent Assembly (CA), elected in May 2008, failed in its mission to give Nepal its badly-needed constitution by May 2012.

The Maoists then lost power in the second CA elections held in November 2013, emerging as the third largest force after the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML.

Nepal's established parties were back on top and their leaders set a new deadline for the constitution: 22 January 2015.

But the work is far from done.

Sticking points

The new political order post-2013 sent the former rebel Maoist party and the newly-emerged Madhesi parties to the opposition benches. Nepali Congress leader Sushil Koirala, who leads a coalition alongside the CPN-UML, took on the responsibility of promulgating the new constitution, where the Maoists had failed.

Yet the same issues which stymied earlier attempts remain. These are:

The names, numbers and borders of proposed federal states. The biggest sticking point is whether or not to federate the country along ethnic lines or names. The Nepali Congress and CPN-UML, who are pitching for multi-ethnic federal states, fear that federating the nation along ethnic lines could lead to conflict or even to it disintegrating.

Forms of governance, such as whether to give executive powers to the president or the prime minister.

The type of electoral system the nation should adopt - direct (first-past-the-post), proportional or a mix of both.

The type of judicial system the nation should adopt - whether to make it federal; the formation of a constitutional court.

Threat of unrest

The opposition players, known for their hard-line postures on federalism, forms of governance and the electoral system, are not giving in easily.

Opposition members scuffled with security officers in parliament on Monday night

Maoist leader Prachanda has demanded that their views be taken into consideration. An alliance of 30 parties including the Madhesi that he leads has already started street protests and strikes.

"Even if the consensus is not made, the sky won't fall," Dinanath Sharma, a Maoist leader, told the BBC.

"If the ruling alliance opts for the so-called voting procedure to end disputes related to the constitution, it will push the nation towards confrontation, which will not be good."

Meanwhile, the bid to restore Nepal to its Hindu state status - by undoing the declaration made after a republic was declared in 2008 - appears to be getting stronger, with the pro-Hindu monarchy party, the Rastriya Prajatantra Party - Nepal (RPP-Nepal), maintaining its campaign.

In the face of frantic political negotiations, one thing is for sure: unless the parties reach a consensus, the proposed Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal will remain a mirage for Nepal's 30-million population.

- Published15 July 2024

- Published20 January 2015

- Published13 January 2015