Lee Kuan Yew: Life in pictures

- Published

January 1969

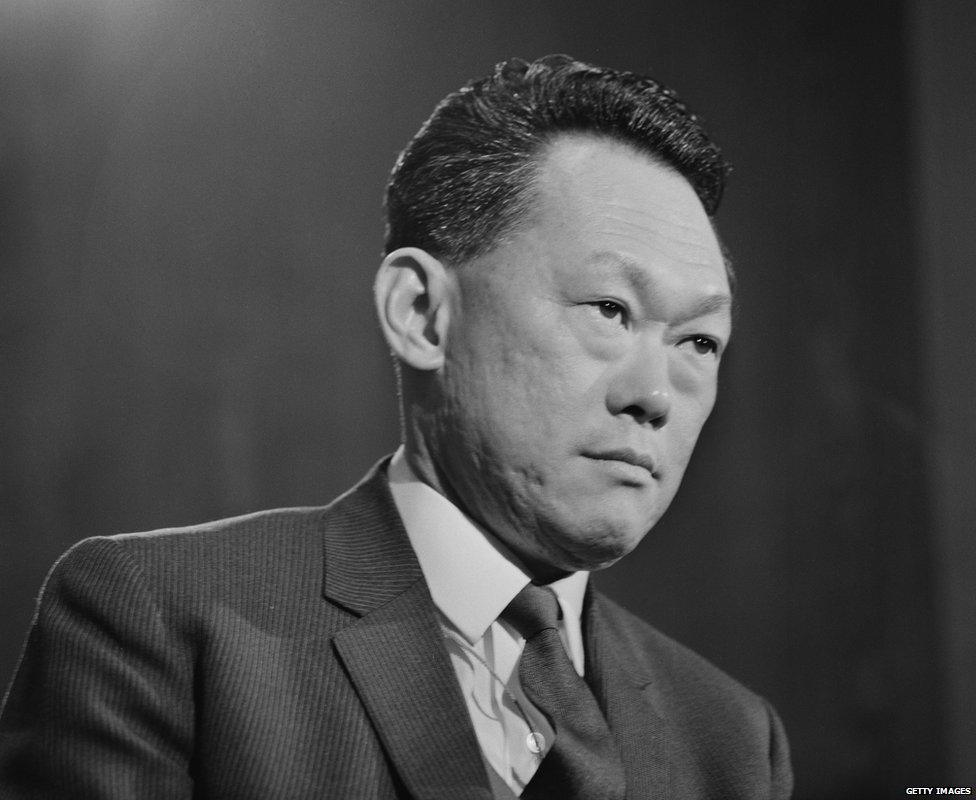

Lee Kuan Yew - known almost universally as LKY - is considered the founding father of modern Singapore, and has been the point around which politics in the city-state has revolved for nearly five decades.

But Singapore's stability and growth have been achieved in part through its only cursory nod towards democracy, and a determined quashing of dissent and free speech.

As news emerges that "The Old Man" has died at the age of 91, the BBC looks back at some key images from his life.

Lee Kuan Yew was born on 16 September 1923 in Singapore, to third-generation migrants from China. He lived for a short period in this house on what is now Neil Road. Singapore was at that time under British imperial rule, meaning he was born a British citizen and grew up with English as his first language - he did not speak Chinese until he was in his 30s. He studied at an English school in Singapore, becoming the highest achieving student in his year in Singapore and Malaysia.

The outbreak of World War Two put Lee's plans to travel to England for further study on hold. In February 1942, the British colonial army surrendered to the invading Japanese, starting a "reign of terror". Lee narrowly escaped being rounded up and killed in the Sook Ching massacre, one of the most large-scale atrocities of the occupation years. He later said he believed between 50,000 and 100,000 people had died, and that the British failure to prevent the massacre was further proof that Singaporeans should be free to rule themselves.

During the war, he went on to work as a Japanese interpreter and ran his own black market glue business.

After the war, Lee belatedly began his university education, studying first at the prestigious London School of Economics and then at Cambridge. While in England he married Kwa Geok Choo (seen above in 1965), a brilliant Singaporean scholar and later lawyer, at a secret ceremony in Stratford-upon-Avon.

In 1949 he turned his back on a possible British legal career and returned to Singapore, where he practised law and became involved in the trade union movement.

Lee Kuan Yew campaigns in Singapore ahead of the 1958 general elections

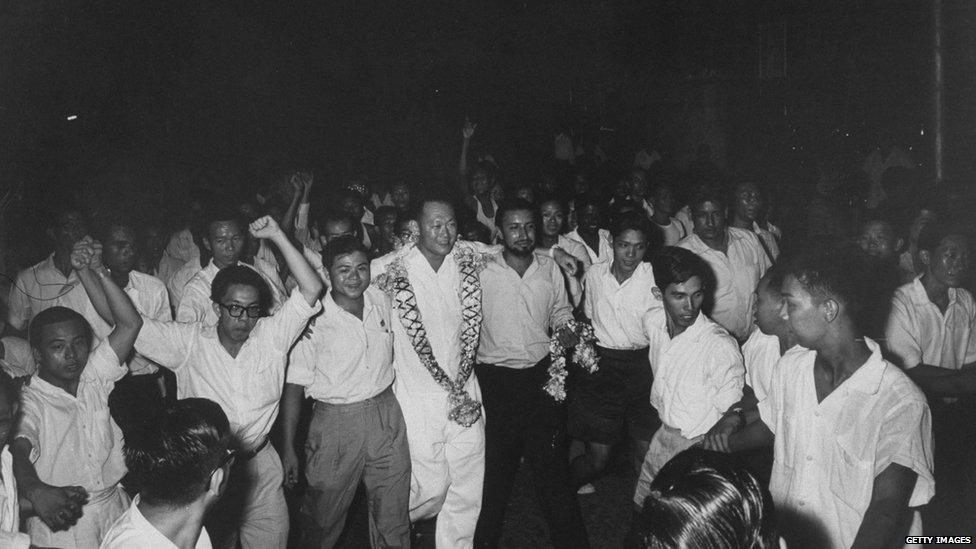

In 1954, LKY became the founder and general secretary of the People's Action Party (PAP), a socialist alliance of Chinese and English-speaking movements which aimed to bring an end to British rule.

In December 1959, Lee - seen above campaigning for a 1958 by-election - was present as Britain granted autonomy to Singapore, though it kept control of foreign affairs and defence.

Two days later, Lee - then aged 36 - was sworn in as the first prime minister of self-governing Singapore, a position he would hold for the next three decades. He embarked on an ambitious five-year programme of slum clearing, building low-cost quality housing, industrialisation and tackling corruption. He spoke fiercely of the need for Singapore to be a multi-racial nation.

The PAP also began campaigning for Singapore to split entirely from the UK and merge into the Federation of Malaya, believing the island to be too small and lacking in resources to survive alone. On 16 September 1963, Lee announced the successful merger from the steps of City Hall, ending 144 years of British rule.

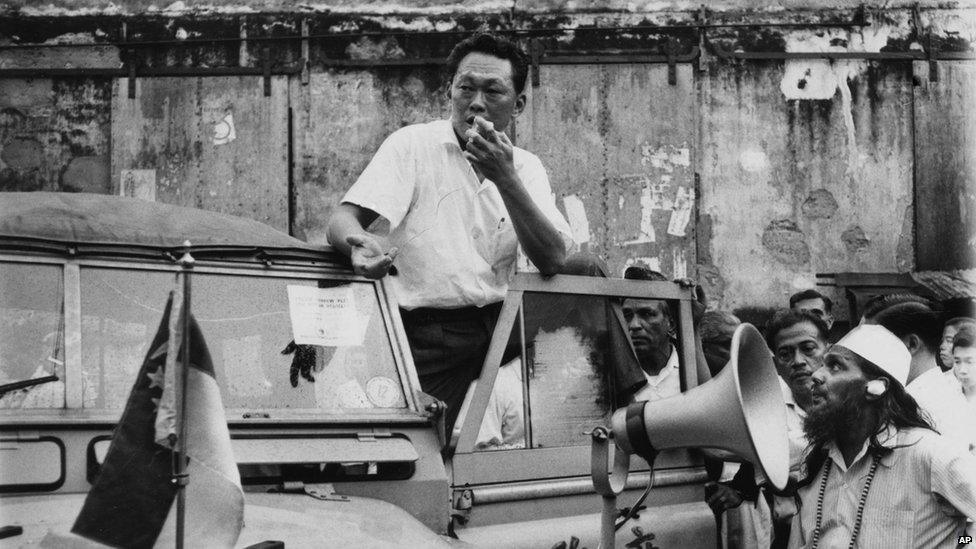

Lee Kuan Yew calls for calm during racial unrest in July 1964

But racial tensions were growing between the Chinese majority in Singapore and Malays over what the ethnic character of the Federation of Malaysia should be. Despite Lee's appeals for calm, several large-scale riots left hundreds injured and more than 20 people dead.

On 9 August 1965, a weeping Lee announced he had agreed to Malaysia's request that Singapore leave the federation to stop the bloodshed from destabilising the union. It was, he said, "a moment of anguish" and went against "everything we stood for". Two days later, Lee declared tiny, isolated Singapore to be an independent nation.

Over the next 31 years, Lee's vision for Singapore turned it from an abandoned and vulnerable colonial outpost to one of the world's wealthiest nations. The country became pioneers in mass house building and nationalised healthcare, while Lee was adamant that education was essential, often saying Singapore's only natural resource was its people, and strongly encouraged well-educated people to marry and have children. Singapore opened up to foreign investment and expertise, recruiting migrant labour widely while enforcing strict racial quotas in housing.

Lee was unapologetic in the face of criticism that Singapore interfered too much in individuals' lives, telling the Straits Times in 1987 "had I not done that, we wouldn't be here today. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think."

Reflecting on his time in power in a New York Times interview in 2010, external he said: "I'm not saying that everything I did was right, but everything I did was for an honourable purpose. I had to do some nasty things, locking fellows up without trial."

Lee was critical of what he saw as the overly liberal approach of the US and the West in general, saying it had "come at the expense of orderly society.

"In the East the main object is to have a well-ordered society so that everybody can have maximum enjoyment of his freedoms. This freedom can only exist in an ordered state and not in a natural state of contention and anarchy," he said in an interview with Foreign Affairs in 1994. He made no secret of the fact that he wanted the PAP to hold onto power.

In 1981 Joshua Benjamin (known as JB) Jeyaretnam - leader of the Workers' Party - won the first ever opposition seat in Singapore. Furious with Jeyaretnam's criticisms of his handling of Singapore, Lee brought repeated defamation lawsuits against him and in 2001 he was declared bankrupt, meaning he could not hold office and was reduced to selling his book on the street to pay his debts. He died in 2008.

Lee was a source of advice for a parade of foreign leaders seeking to better understand Asia.

Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping visited Singapore in 1978 to learn more about its model of development. UK Prime Minster Margaret Thatcher said Lee had a way of "penetrating the fog of propaganda and expressing with unique clarity the issues of our time and the way to tackle them", while US diplomat Henry Kissinger said no world leader had taught him more than Lee Kuan Yew.

When they met in 2009, US President Barack Obama described Lee as one of the "legendary figures of Asia in the 20th and 21st Centuries".

In her later years, Lee's wife Kwa Geok Choo suffered from ill health and dementia and was confined to bed. In the 2010 New York Times interview, he said the stress of caring for her was harder than anything he had faced in politics.

"She understands when I talk to her, which I do every night. She keeps awake for me; I tell her about my day's work, read her favourite poems," he said. The agnostic Lee told the Times he had taken up Christian meditation to "keep the monkey mind from running off into all kinds of thoughts".

Kwa died in October 2010. Thousands lined the streets to pay tribute, or visited her body lying in state.

"Without her," Lee said at her funeral, "I would be a different man, with a different life".

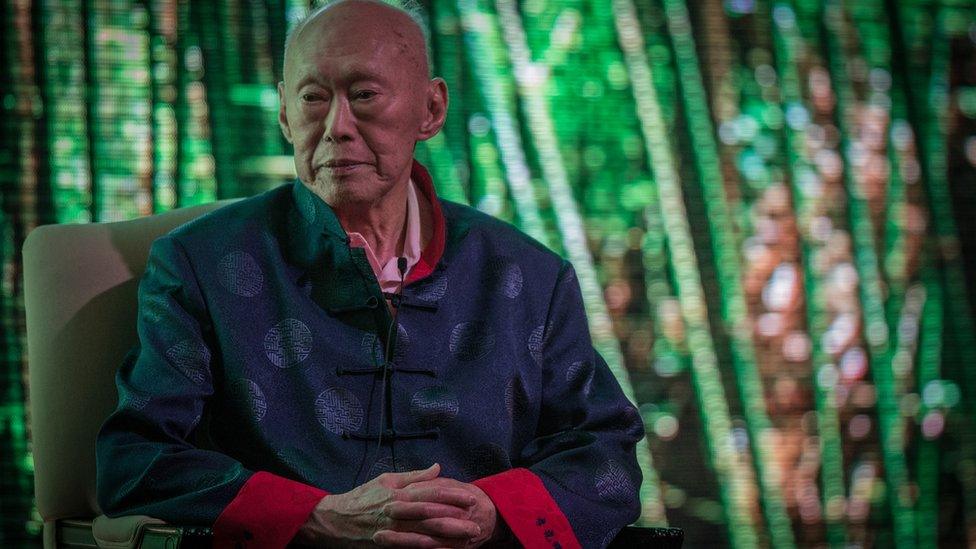

Lee's political involvement continued almost until his death. Though he stood down as prime minister in 1990 he remained a senior minister, his opinion sought on all matters. He represented the Tanjong Pagar constituency in central Singapore for almost his entire political life, campaigning for office here in 2011.

One of his last major public appearances was at the age of 90, when he attended celebrations for Singapore's National Day, marking 49 years since he signed the deal which had filled him with such dread. He died months before seeing the 50th anniversary.