Ray of light in Pakistan's drought-hit Thar desert

- Published

The BBC's Shahzeb Jillani taste tests the freshly filtered water

For three years, the Thar Desert in south-east Pakistan has been suffering from drought-like conditions. But a new solar-powered project to treat underground saline water is offering a ray of hope for the neglected region.

In an isolated desert village, Laxmi Bheel picks up a hand potted clay pitcher and balances it on her head. Covered in a green scarf, a matching top and a long swirling skirt, she walks barefoot in the sand to a nearby well.

Every now and then she supports the pitcher by lifting her arms, which are covered in white traditional plastic bangles. Like most women across this land, it is her job to fetch the water - at least twice a day, every day.

When she arrives at the well, Laxmi uses a long rope, a pulley and a pair of donkeys to take out water from the 200-300m deep well. It is a laborious and repetitive task. At the end of it, the water she carries home is often contaminated and unfit for human consumption.

Laxmi Bheel lives in one of Pakistan's most neglected areas

And yet, in the absence of clean water, that is what they must drink.

The Tharparkar region is one of the most neglected areas of Pakistan. It hasn't seen proper rain for three years. The calamity has taken a huge toll on people and livestock.

"There's hardly anything left to eat and to feed my goats; many of them have already died," says Laxmi, as she cuddles a restless skinny little goat suffering from an eye infection.

Laxmi was born into a low-caste Hindu family. She never went to school and doesn't know how old she is. "Probably 40 or 50," she reckons. Do you have children, I ask. "Yes, about six," she says, and then adds: "That's out of 11. The rest of them died because of disease."

The water-stressed region is prone to drought-like conditions because of inadequate and erratic rain. The region has plenty of underground water, but much of it is saline.

Waterborne diseases and malnutrition are the most common causes of death. In 2014, local media blamed hundreds of infant deaths on the drought.

But the calamity is not new or unexpected. Every few years, tens of thousands people move to greener pastures in nearby farming districts, closer to the River Indus.

Healthcare workers often leave the area for more lucrative jobs elsewhere

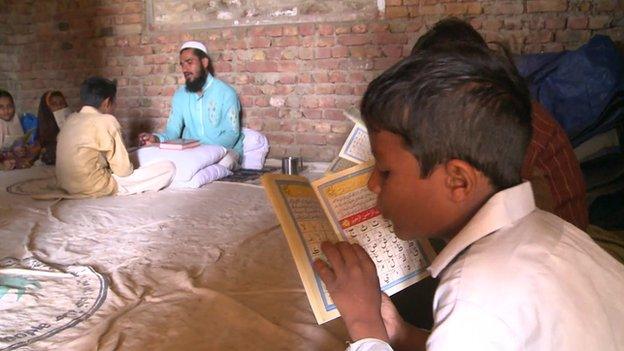

Villages often have no schools, and schools often have no teachers

The last time I was in Tharparkar in 2000 it was to report on one of the more severe droughts this region has experienced.

Fifteen years later, in some ways much has changed.

Back then, I remember travelling for hours on sandy tracks in a rickety old World War Two American truck called Kekra (meaning tortoise). These slow-moving trucks were the main mode of transport between border towns and the district capital Mithi. Today, there are shiny new roads linking most of the major towns in Thar.

Back then, radio was the only mass medium and news travelled by word of mouth. Today, the arrival of mobile phones in the main villages has transformed the way people can connect with each other and the rest of the world.

Electricity infrastructure is still lacking. But solar power has gained momentum.

Travelling in Thar these days, it is not uncommon to come across roadside vendors offering to charge your mobile phone using solar panels.

And yet, despite these improvements in communications, social sectors like health and education have continued to suffer.

Water scheme

This region has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the country. On most measures of development, Thar is at the bottom of Pakistan's 120 districts.

Doctors and nurses are hard to find. Qualified medical staff from the region often leave to earn much more money in big cities like Karachi.

In Thar, there are many villages without schools and many schools without teachers.

The new water system promises much, but supplies remain sporadic

It's part of an overall crisis of governance, say critics. They blame the provincial government of Sindh - run by the party of former president Asif Ali Zardari - for corruption and institutional failures.

But the government defends its performance by pointing to its massive investment in a new scheme to bring clean drinking water to the region.

The $33m project involves installing 750 water purification projects in villages across the desert region. Of these, as of this month, about 280 have already been installed, says PakOasis, the company running the project.

The scheme is being billed as a ray of hope for Thar. It uses imported Danish technology to pump underground water. Impurities from the water are then removed using American membrane technology. The filtration process is called Reverse Osmosis (RO).

Each RO plant runs on zero-electricity cost. It is powered by solar panels imported from China.

The biggest of these water plants stands on a hill near Mithi. It has the capacity of purifying 2 million gallons of water daily. At its full capacity, it is expected to benefit 300,000 people.

The project was meant to go online later this year. But reeling under heavy public criticism for not doing enough, the government inaugurated it with much fanfare in January.

'Precious asset'

The project has faced some initial teething problems.

Some of the smaller RO plants were reported shut soon after they were installed.

The company says that's often because locally hired plant operators are not up to the job.

"We are required to employ them on the recommendation of local politicians. Sometimes, these guys lack the qualification and skills to operate the plant," says a company official.

But he adds: "We are here to train them and troubleshoot any problems, but we accept that for some it will take a while to figure out the technology."

Mian Fayyaz Rabbani, the relief inspecting judge for Thar, says: "If implemented properly, this project has the potential of bringing about the single biggest positive change in the quality of life here."

He was appointed last year by the provincial High Court to keep a check on the government's relief operation.

Thar has an abundance of underground water, say experts.

"Imagine what these solar powered RO plants can do," says Mr Rabbani.

"The access to clean water will prevent deaths from waterborne disease. The water can be used to irrigate farmlands to make village self sufficient in food.

"It could help save thousands of livestock, which are the most precious asset for people in this part of the country."

- Published17 March 2014