Thein Sein: Myanmar army to continue key transition role

- Published

Thein Sein: "As we mature in democracy in our country, the role of the military in parliament will reduce gradually"

Myanmar's army will continue to play a key role in the move towards greater democracy, the president has said.

Speaking to the BBC in the capital Nay Pyi Taw, Thein Sein said the military had initiated reforms but he put no timeframe on reducing its dominant role in Burmese political life.

Thein Sein's four years in office have seen significant changes but the army's power remains untouched.

The military still occupies a quarter of the seats in parliament.

It also has a veto over constitutional change and the right to seize power outright at any time.

During our 45 minutes together I'd expected the president to put a little distance between himself and the army. He's an ex-general, of course, but he's now a politician and has a reputation as a reformer.

'National interest'

I thought I'd hear him say that he was trying to slowly coax the Burmese army to take a step back and submit to civilian control. What I got was a forceful justification of why Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, still needs the military involved in politics.

"It's not true that reforms have stalled because of the military," he said.

"The Tatmadaw [Burmese army] does not get involved with political parties and is only concerned with the national interest."

Thein Sein would not put a timeframe on a reduction in the military's political role

"The military has two tasks. One is to fight for the country in case of war. If there's no war they will serve the interest of the people. Serving the interests of the people means being involved in national politics."

The 69-year-old believes that having initiated the move away from dictatorship, the army remains a necessary part of the transition.

"In fact the military is the one who is assisting in the flourishing of democracy in our country," he says. "As the political parties mature in their political norms and practice, the role of the military gradually changes."

The president refused to put a timeframe on a reduction in the military's political role, saying it would be done gradually and in line with the "will of the people".

Throughout our discussion the president spoke with certainty. Convinced that the army had the full support of the people and that it would always act in the national interest.

The military won't be standing in November's general election but its popularity will be tested.

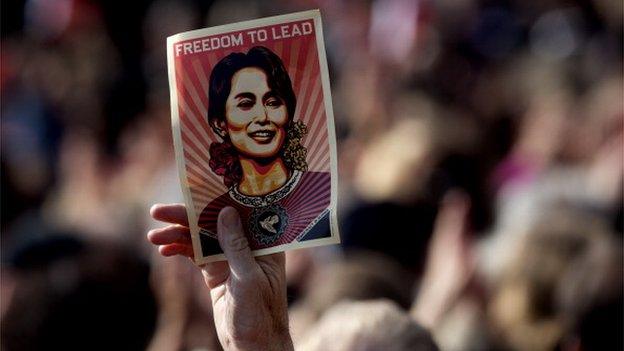

The USDP, a military-backed party full of former officers, will for the first time go head to head with Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy.

Most expect the NLD to win, but Ms Suu Kyi is barred from assuming the presidency because her children hold British passports.

Thein Sein argued that other countries place nationality restrictions on eligibility for the top job

The president said he wouldn't mind the constitution being changed, but that it was up to parliament and then, if necessary, the will of the people in a referendum.

Ms Suu Kyi's problem of course is that the army says it will veto the needed change in parliament, so it won't get put to a public vote.

Despite indicating a willingness to see the Aung San Suu Kyi clause (59F) removed, it was left deliberately vague as to whether the president actually wanted this to happen.

The impression was certainly that he wouldn't be pushing for change.

I was told that the eligibility restriction dated back to 1947 and was partly drafted by Aung San Suu Kyi's father. It's a fact hotly contested by Ms Suu Kyi's supporters.

"Our country is situated between two populous countries in India and China. So the leaders of our country have always had to safeguard our sovereignty and integrity to avoid being dominated," President Thein Sein said. "These concerns were considered and drafted into our constitution."

He then cited the example of other countries where eligibility for the top job is restricted on nationality grounds, before mentioning Henry Kissinger as someone who would have made a good American president but was blocked by the rules (because he was born in Germany).

'Domestic affair'

In the last six weeks intense fighting with rebels in the small mountain region of Kokang have claimed the lives of more than 200 combatants, and an unknown number of civilians.

For now the solution to the Kokang rebel conflict has been a military one

Kokang rebels have been crossing the border at will, and last week Burmese jets were accused of bombing China by accident, killing five Chinese sugar cane farmers. The war has put a severe strain on Myanmar's most important international relationship, with China.

Though most accept that at a local level Chinese officials are assisting the rebels. the president was unwilling to blame Myanmar's much larger and richer neighbour.

"This is a domestic affair and we have to solve it domestically," he said.

"China cannot solve it. We have to sort it ourselves. China has a policy of non-interference and have already said they will not accept any group that attacks Myanmar from within their territory."

For now the Burmese solution is a military one with the Kokang rebels' offer of talks rejected.

- Published17 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published17 February 2015

- Published8 July 2015