Sewol ferry: How to raise the wreck from the sea bed

- Published

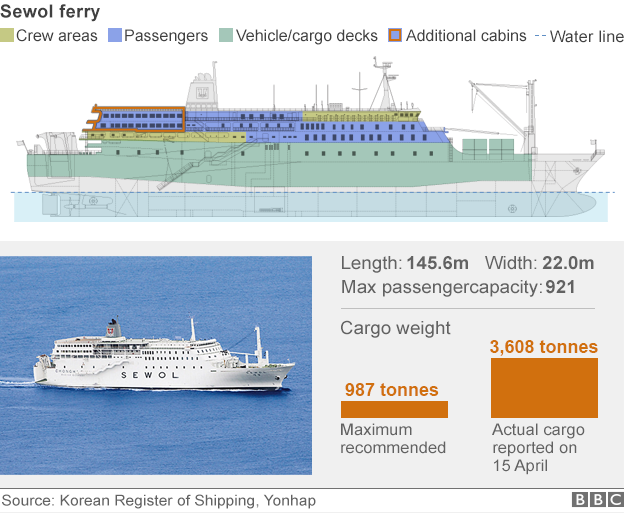

The Sewol ferry sank days after capsizing in April 2014 - it will now be salvaged from the sea bed

South Korea's president has promised the wreckage of the Sewol ferry will be raised at the earliest opportunity. But is it that straightforward?

The ferry sank in April 2014 causing the deaths of 304 people, and now sits on its side on the sea bed.

Experts say the salvage operation could be complicated by a number of factors.

But the government is hopeful it can be lifted in one piece - and has put forward plans for how to do so.

The ferry sank in waters between 37 and 43 metres (121 and 141 feet) deep.

While salvage operations have been undertaken in deeper seas, the site of the Sewol is subject to dangerous currents and, on the surface, heavy winds.

Two options

At a press conference on 10 April, South Korea's Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries outlined how the ship could be lifted.

The ministry said a recovery of the ship in one piece was "risky, but technically possible".

First option

Attach chains to ferry

Cranes lift the Sewol directly from the sea bed to the surface

Ferry placed on large inflatable ring on the surface

Second option

Attach chains to ferry

Cranes lift Sewol a few metres higher up the sea bed

The ferry is gradually moved to shallower waters

The ferry is lifted out of the sea

One option would see 93 holes drilled in the side of the ferry to allow chains to be attached.

The ferry would then be lifted by cranes placed on boats, before being moved onto a floating dock on the surface of the sea.

A second option would see the Sewol lifted to a shallower part of the sea bed where there is better visibility.

It would then be gradually lifted until it reached an area with weaker currents.

Lee Kyu-yeul, the head of the ministry's salvage task force, said he preferred the second option.

"For plan one, there is a risk that the ferry could be destroyed into pieces if the crane wires fail to sustain it due to unexpected strong currents," he said.

Heavy winds and strong currents hampered the search for survivors of the ferry disaster

The wreck of the Costa Concordia was floated using air-filled tanks

Tunnel in the sand

John Noble, a director with Constellation Marine Services, a salvage company, said there was a third possible option.

"They could try and get slings around the hull and lift it up that way," he said.

"It depends on the sea bed. If it's sand, you can bury a tunnel underneath the hull to hook the sling there. But if it's rock, they would have to blast some of it away."

Mr Noble said the recovery would be "very, very different" to that of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, which was raised using inflatable tanks after capsizing in Italy in January 2012.

He said: "It won't be anything like the type of salvage operation you had with the Costa Concordia - in design and from a finance point of view."

The final cost of the operation is likely to be made public only once the salvage company is announced. But some reports in South Korea say it could cost as much as $137m (£92m).

'Much more tricky'

Mark Hoddinott, the general manager of the International Salvage Union, said: "It sounds like they will try and lift it in one piece, mainly because they suspect there are still bodies on board and they don't want to break it up.

"This will make it much more tricky. The easiest thing would be to cut it into sections and lift the smaller pieces, which isn't that challenging, technically.

"So this is going to require very careful rigging to lift it. And they are going to have to spend a lot of time ensuring that the ship isn't going to break in two."

Mr Hoddinott also warned of another potential major obstacle.

"One of the biggest issues is that these ships do tend to fill up with mud if they've been underwater for any amount of time.

"So if it is full of mud, that will present a real issue as it will make it much heavier to lift."