Is China-Pakistan 'silk road' a game-changer?

- Published

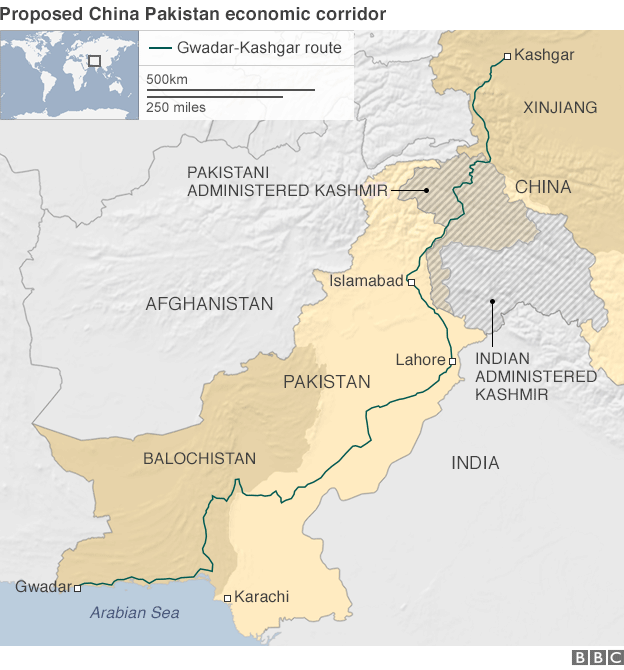

China has announced a $46bn investment plan which will largely centre on an economic corridor from Gwadar in Pakistan to Kashgar in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. The BBC's M Ilyas Khan looks at the significance of the plans.

Why has this got people talking?

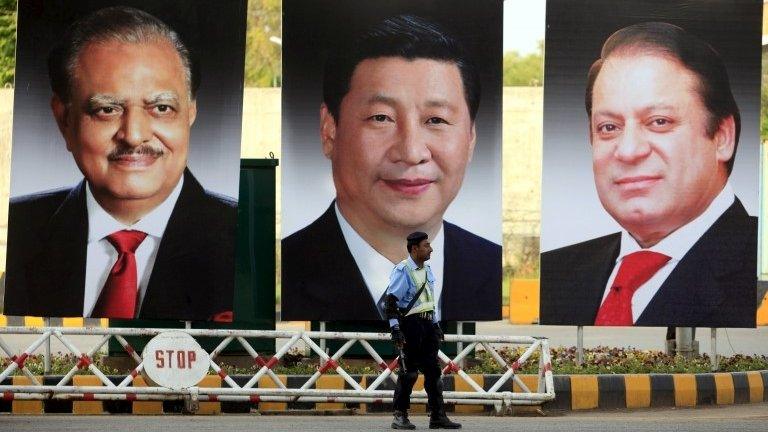

Pakistan describes its friendship with China as "higher than the Himalayas"

The money China is planning to pour into Pakistan is more than twice the amount of all foreign direct investment (FDI) Pakistan has received since 2008, and considerably more than the entire assistance from the United States, Pakistan's largest donor until now, since 2002.

Pakistani officials say most projects will reach completion in between one and three years, although some infrastructure projects could take from 10 to 15 years. So the investment is not going to be spread too thin over a longer period of time, as happened with the US assistance.

Also, this investment will be heavily concentrated in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a combination of transport and energy projects and the development of a major deep-sea port offering direct access to the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Experts say this will create jobs and spark economic activity in Pakistan which over the last three decades has become a cranky, rent-seeking military power torn by armed insurgencies and a failing system of service delivery.

But as defence analyst Professor Hasan Askari Rizvi warns, the real game changer is not the signing of deals, but their timely execution.

But what will happen to all that money?

Nato supplies passing through Pakistan were repeatedly attacked by the Taliban

Officials admit that some deals already signed by China and Pakistan in 2010 might not reach completion. If that turns out to be the case, they admit it will mostly have been due to incompetence, corruption and lack of transparency.

So if anything is to come out of the present deals, the Pakistanis will need to work harder to fulfil their part of institutional, legal, financial and logistical commitments.

Some level of corruption is expected at both ends, and neither country is known for encouraging transparency. So we may not know until much later how much of this money is coming in the form of loans, how much in grants and how much in the shape of public or private investment.

There is also a political dispute brewing in Pakistan, with some politicians threatening to oppose the corridor if its route is not planned along some specific areas.

Economic expert Dr Kaisar Bengali says that while Pakistan has many problems to overcome, its move to end militant sanctuaries in the north-west has created an air of expectancy, and the arrival of Chinese investment at this time suggests Pakistan has a once-in-a-lifetime chance to make an economic turnaround.

"This is Pakistan's first opportunity since the 1960 Indus Water Treaty to change its economic geography," he says.

And what about militants?

The economic corridor starts at Gwadar and ends at Kashgar.

Gwadar is located on the Arabian Sea coast of Balochistan, a province in south-west Pakistan which is wracked by a decade-old separatist insurgency.

Construction at Gwadar began more than a decade ago

Kashgar is located at the centre of China's only Muslim-majority, Turkic-speaking Xinjiang region. It is populated mainly by ethnic Uighur Muslims, and has been home to a separatist movement since the mid-1990s. There has been a recent upsurge in violence which China blames on separatist "terrorists".

Between Gwadar and Kashgar, the corridor passes through areas that are within striking range of Pakistan's Taliban insurgents. Until recently they controlled territory along Pakistan's north-western border with Afghanistan, and hosted the largest concentration of Uighur militants outside China. They still have a presence in the border region, though their sanctuaries have been disrupted by a Pakistani military operation that began last June.

Both Uighur and Pakistani Taliban militants have been targeting Chinese nationals in Pakistan. The Baloch insurgents have their roots in socialist ideology, but they too dismiss the Chinese as allies of Punjab, Pakistan's most populous province which they accuse of "robbing" Balochistan's resources.

The super highway will originate in Pakistan's restive Balochistan region

A former diplomat, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, said in a TV debate that the Pakistani army has decided to raise a special force to safeguard this 3,000km corridor.

Many are sceptical because the army previously failed to ensure a trouble-free supply to Nato troops in Afghanistan.

But some believe the military is likely to treat the Chinese corridor differently because the economic benefits accruing from it could help isolate Baloch insurgents.

Why is China doing this?

Pakistanis have long described their "friendship" with China as higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the oceans, and as information minister Pervez Rashid put it more recently, sweeter than honey. But behind these lofty words lie some hard-core interests.

The route would allow China to by-pass the Malacca straits to reach Africa and the Middle East

China has been a more reliable and less meddlesome supplier of military hardware to Pakistan than the US, and is therefore seen by Pakistanis as a silent ally against arch-rival India.

Friendly exchanges with China also help Pakistan show to its "more volatile" allies in the west, notably the US, that it has other powerful friends as well.

For the Chinese, the relationship has a geo-strategic significance.

The corridor through Gwadar gives them their shortest access to the Middle East and Africa, where thousands of Chinese firms, employing tens of thousands of Chinese workers, are involved in development work.

The corridor also promises to open up remote, landlocked Xinjiang, and create incentives for both state and private enterprises to expand economic activity and create jobs in this under-developed region.

The project is expected to bring change to Xinjiang as well as Pakistan

China could also be trying to find alternative trade routes to by-pass the Malacca straits, presently the only maritime route China can use to access the Middle East, Africa and Europe. Apart from being long, it can be blockaded in times of war.

This may be the reason China is also pursuing an eastern corridor to the Bay of Bengal, expected to pass through parts of Myanmar, Bangladesh and possibly India.

Experts say much of Chinese activity is geared towards boosting domestic income and consumption as its previous policy of encouraging cheap exports is no longer enough to sustain growth. On the external front, it is investing in a number of ports in Asia in an apparent attempt to access sources of energy and increase its influence over maritime routes.

What do the US and India think?

There are indications the Americans have been encouraging China to play a stabilising role in Afghanistan. And few in Pakistan believe that American influence is likely to significantly recede from this region in the short run.

In the long run, though, the Americans will definitely be working on strategies to cope with the rise of Russia and China, and what that means for the resource-rich regions of Central Asia and the Middle East.

Likewise, while the Indians have China as one of their largest trading partners, they may have long-term security concerns about Chinese control of the Pakistani port of Gwadar.

- Published20 April 2015

- Published20 April 2015

- Published20 April 2015