Nepal earthquake: The challenges of disaster relief

- Published

Aid has begun to reach remote regions near the epicentre of Saturday's devastating earthquake in Nepal

Logistics, averting the bottlenecks, co-ordinating the efforts of governments and aid organisations big and small - they quickly become the preoccupations of those overseeing disaster relief operations, like the one following the Nepal earthquake now.

The large-scale sudden disasters of recent decades have taken place amid rapid change in global communications and the development of more systematic strategies for responding to such emergencies.

But, as I have seen covering a number of earthquakes in different parts of the world, each disaster tests the response in new ways.

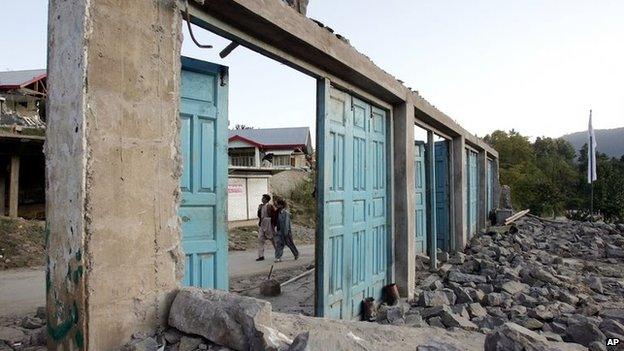

Access problems - the 2005 quake in Kashmir

The urgent appeals from Nepal's government for more helicopters for the rescue and relief operations echo an impassioned appeal made a few days after the devastating earthquake in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and north-west Pakistan in October 2005.

I was among the journalists covering the visit of the then UN emergency relief co-ordinator, Jan Egeland, to the main city in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, Muzaffarabad.

The 7.6-magnitude earthquake six days earlier had caused massive damage in the city and elsewhere smaller towns and villages had been wiped out.

Around 80,000 lost their lives in the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan-administered Kashmir

As in Nepal today, landslides had compounded the impact of the earthquake and blocked and destroyed roads in the mountainous terrain.

As Mr Egeland assessed the progress of the relief operations that day, it was already estimated that at least 23,000 people were dead. Eventually, the disaster was to claim about 80,000 lives.

He told us at the end of the visit that he had never witnessed such devastation before. He called it "a complete nightmare".

Identifying the biggest challenge as reaching outlying areas, Mr Egeland called for a rapid tripling of the number of helicopters - and said that he did not believe or accept that this would be impossible.

Survivors of the earthquake in Pakistan were asked to try and make their own way to relief centres

At the same time, the then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, talked about the threat of "a second massive wave of death" if efforts were not stepped up.

It was hardly an exaggeration, with the onset of winter imminent.

Increasing numbers of helicopters were committed to the relief operation. Some of the crucial heavy lifting was carried out by military helicopters brought in from neighbouring Afghanistan.

Despite this and all the other efforts that were being made to get aid out to the more isolated communities, 18 days after the earthquake Pakistan's then Prime Minister, Shaukat Aziz, appealed to survivors to try to make their own way down to valleys and to larger centres if they could.

Spontaneous response - the 2001 India quake

In India in January 2001, a 7.7-magnitude quake flattened towns and villages in the Kutch region of Gujarat and also brought down multi-storey buildings in Gujarat's state capital, Ahmedabad.

That disaster claimed around 20,000 lives.

Among the many structures destroyed in Bhuj, the main town in Kutch and near the earthquake's epicentre, were historic buildings, as in Kathmandu today.

The narrow streets and alleyways of Bhuj's oldest quarter were piled so high with rubble and debris that it made the task of search and rescue teams all the harder - though some people were pulled out after several days.

Ordinary citizens played a key role in the relief effort after the Gujarat earthquake in 2001

But there was a factor in the Gujarat earthquake response that often gets little attention in the way we perceive disasters and relief operations.

India tends to handle its own natural disasters where possible rather than immediately appeal for outside aid, and its civil society organisations and ordinary citizens will invariably respond spontaneously.

After first seeing the impact of the earthquake in Ahmedabad - and watching friends and neighbours joining rescuers in trying to dig into the ruins of the collapsed apartment blocks - we navigated our way around the gaping cracks in the road to Bhuj.

Already people were turning up from far away in packed cars and pickups and just dropping off food, water and clothing, sometimes leaving it literally by the roadside.

Government destroyed - the 2010 Haiti quake

In the earthquake in Haiti in January 2010 the challenge was not just the enormity of it but the deadly blow that it struck to the administration of the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.

More than 200,000 people were killed, according to the Haiti government, and huge numbers were made homeless.

More than half of the government and administrative buildings in the capital, Port-au-Prince, were destroyed or damaged, one civil servant in four in the capital died, and the headquarters of the UN mission collapsed.

Communications and air and port access were disrupted. Delays in distributing aid became a growing problem and led to protests.

Huge numbers of people were made homeless after the earthquake in Haiti

In that disaster, the military of several nations played a key role in overcoming the bottlenecks.

Within a few days, the American carrier, USS Carl Vinson, arrived with 600,000 emergency food rations and other supplies.

A hospital ship was sent too. And at stadiums and other distribution points I watched as helicopters ferried aid back and forth.

Whether in response to earthquakes or hurricanes, cyclones or typhoons or floods or other natural disasters, humanitarian assistance has become much more professionalised and structured.

Fuelling discontent - the 1978 Iran quake

Compare with 1978, when I covered my first earthquake in Tabas in eastern Iran.

The 7.4-magnitude quake killed more than 15,000 people, and one eyewitness said that the town of collapsed mud-walled and brick houses had "turned into a graveyard".

The international response to Nepal's earthquake will continue to be under intense scrutiny

We were just a handful of journalists flown in some 48 hours after the earthquake by the Iranian air force, and flown out again a few hours later with the plane full of the injured and homeless.

The handling of the earthquake fuelled discontent with the Shah's government, with the Iranian revolution just a year away, but international attention seemed to wane rapidly.

The complex challenges of responding to the Nepal earthquake continue under intense scrutiny. And that is before work begins on the ambition with every such disaster today - to "build back better".