China eyes growing Japanese influence

- Published

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is building relations with the US

It was springtime in Washington for the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe this week.

His visit included trips to the Lincoln Memorial, the Arlington Cemetery and an address, external to both Houses of Congress - the first time this honour has been afforded to a Japanese leader.

And no wonder. The visit heralded a significant reinforcement of the alliance between Washington and Tokyo.

Given the continuing dramas in the Middle East, the Obama administration's signature policy shift - its pivot to Asia, external - is being pursued in more of a minor rather than a major key.

But regardless of the old business in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere, the pivot is continuing; preparing Washington for its role in what it set to be the Pacific century, external.

In this the Americans expect to have Japan at their side and Mr Abe, through both his desire to update Japan's defence posture and his economic reforms is reinforcing Japan's claim to be Washington's chief partner of choice.

This visit emphasised the crucial importance of both security and economics in the future of the Asia-Pacific region.

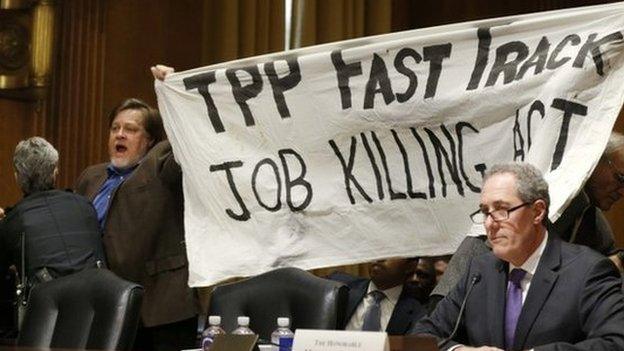

As important as new defence guidelines and a reinforced security partnership was further discussion of the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP); a 12-nation trade deal which is very much a shared initiative between Mr Obama and Mr Abe.

Chinese concern

Watching all this from the sidelines is of course Beijing. A victim of Japan's militarism during the past century, China views Japan's military modernisation and expanding security horizons with some concern.

The Izumo is Japan's largest warship since World War Two

China though - because of its own growing defence capabilities and regional, if not global ambitions - is very much the reference point that is prompting military reform and modernisation across the region.

It's a powerful reminder that as much as grand strategy and economics, history is also a powerful factor in the Asia-Pacific.

Highest spending on defence (2013):

US: £420bn

China: £123bn

Russia: £57.5bn

Saudi Arabia: £44bn

France: £40bn

UK: £38bn

Germany : £32bn

Japan: £31.8bn

India: £31bn

South Korea: £22bn

Japan's military reforms, most importantly the desire of the Abe government to revise constitutional provisions limiting the role of the country's so-called "self-defence" forces are very much part of this.

Japan's post-war US-drafted constitution was specifically intended to prevent a resurgence of Japanese militarism.

And tensions persist given perceptions in many countries that Japan has been insufficiently explicit in its apologies for its behaviour during World War Two.

This has prompted particularly bitter recriminations, for example, between Japan and another of Washington's key allies in the region, South Korea.

Some 70 years on from the end of World War Two Mr Abe sees these constraints on the armed forces of a democratic Japan as imposing an unnecessary exceptionalism that hampers the country's ability to defend its interests.

Expanding role for Japan

The important new defence guidelines agreed with Washington give Japan roles in new areas like cybersecurity and space.

But they also broaden the remit of Japan's armed forces, enabling them to operate with the US and other allies in new ways that are not restricted to the narrow and direct defence of Japanese territory itself.

Thus, Japan is on the way to becoming a more effective military ally of the US able to operate alongside it in joint missions.

It is by no means clear of course that public opinion in Japan is entirely in tune with Mr Abe's desire for constitutional change.

But the fact remains that even under the existing remit Japan has become a much more significant player in the international system.

Five small islands and three rocks in the East China Sea are disputed by China and Japan

Over the past 10 years Japanese forces have been despatched to Iraq and Kuwait.

Japanese peacekeepers have been deployed in South Sudan and Haiti and it has participated in Operation Enduring Freedom - Washington's broader counter-terrorism operation - in the Indian Ocean.

What especially worries China is Japan's own military modernisation.

It is deploying ballistic missile defences - directed in the first instance against the potential threat from North Korea's missile arsenal.

And Japan recently commissioned its largest warship since World War Two - the Izumo - described as a helicopter-carrying destroyer but potentially a small aircraft carrier.

Its chief mission - anti-submarine operations and command and control.

It is a significant reinforcement, external of Japan's ability to defend its interests in the East China Sea.

Territorial disputes

Disputed territorial claims have turned the tensions between China and Japan into a favourite subject for a whole genre of futuristic fiction with writers seeing this as the spark that might set off a third world war in Asia.

For the US and Japan, broader defence ties are intended to make this less likely.

China has increased its spending on the military by 10%

But their defence relationship still begs bigger questions about Washington (and for that matter Tokyo's) strategy towards Beijing.

Is the US goal co-operation with or containment of a rising China?

Just where should the line between these two options be drawn?

And does China want harmony or hegemony?

The answers to these questions are likely to determine whether the coming Pacific century is marked by peace or conflict.

- Published29 April 2015

- Published22 April 2015