Kim Jong-un: Trying to make sense of North Korea's leader

- Published

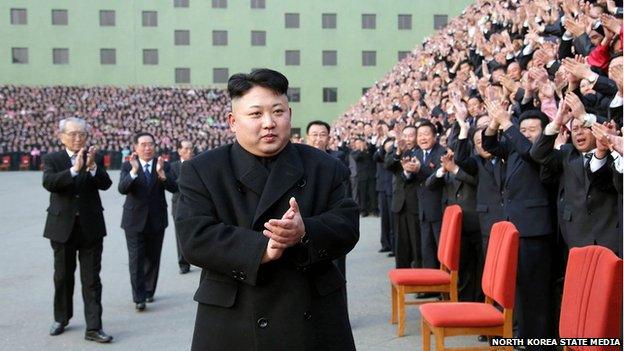

Kim Jong-un's public appearances prompt wild applause at home

There must be some truth in between, mustn't there?

Outside North Korea, Kim Jong-un is depicted as a monster. Or a buffoon who sends his goons around to a London hairdresser who dared to poke fun at his haircut, external. Or a portly playboy, external with a liking for Swiss cheese, fast cars and faster women.

But inside North Korea, he is a monarch, the supreme leader, with an almost god-like aura. His people applaud until their hands must be raw.

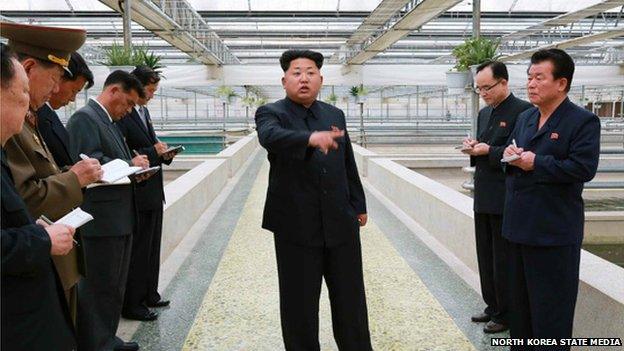

The state media reports how he travels the country and imparts his guidance, recently, for example, on farming terrapins.

The Rodong Sinmun, external, the official newspaper of the Korean Workers' Party, reported that the breeding establishment in Pyongyang had been set up on the initiative of his father, Kim Jong-il, "to provide the people with tasty and nutritious terrapin widely known as precious tonic from olden times".

His guidance was sorely needed because it transpired that the farm had not been performing well either in breeding terrapins or ideologically. The newspaper quoted Kim Jong-un thus: "It is hard to understand that the farm did not arrange even the room for the education in the revolutionary history."

On top of that, a venture to breed lobsters had failed. This was not a good day at the Taedonggang Terrapin Farm.

Kim Jong-un imparted his guidance at the Taedonggang Terrapin Farm

Feeling of 'could be next'

This all illustrates how difficult it is to make sense of the man. The image of the global bete noir is burnished or tarnished by propagandists on all sides. But the recent allegations from the South Korean intelligence agency that a purge of officials had been taking place took people by surprise, proving that he is unpredictable even for experts in North Korea.

Outside experts are not hopeful. Some think his recent actions have been erratic in a way which was not there with his father. Under Kim Jong-il, the people around him tended to survive - generals kept their jobs and their heads - and this meant that the leadership circle supported the leader.

Now, so the argument runs, the sudden execution of Kim Jong-un's mentor and uncle, Chang Song-thaek, and perhaps of the Defence Minister, Hyon Yong-chol, must make those around him fear that they might be next - and fear of sudden and unpredictable death might lead people with power to act first.

Aidan Foster-Carter, honorary senior research fellow at Leeds University, says: "If loyal cadres feel they could be next, at any time and for no reason, that undermines loyalty and could even be an incentive to defect."

Or worse: "If the elite doesn't feel safe, you wonder in what circumstances they might move against him."

Out of his depth

It then becomes a calculation of whether loyalty or extreme disloyalty minimises danger.

Plotters don't tend to have long life expectancies:

the plots to kill Hitler all failed, and those plotters who were caught were invariably executed

Stalin eliminated all potential opposition

in South Korea, President Park Chung-hee was assassinated over dinner, external by his own intelligence chief, who was then tried and hanged

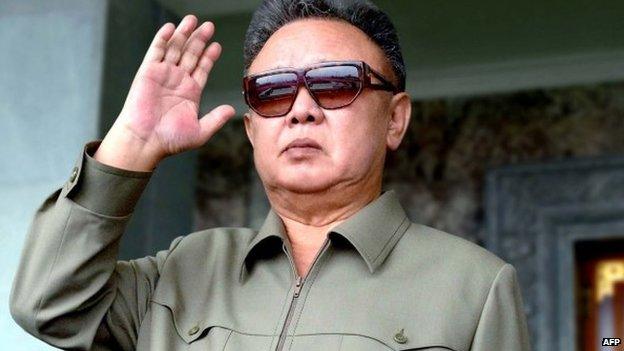

Some analysts suggest the North Korean leader is not the intellectual equal of his father, Kim Jong-il

Mr Foster-Carter detects a man who is out of his depth. "There's no evidence of ability," he told the BBC. "Kim Jong-il was unknown for a while, but we now know that he was very competent. He had had 20 years being groomed for leadership by his father."

Kim Jong-un, in contrast, was catapulted into the job in his late 20s after spending much time abroad, in Switzerland at school, so he's something of an outsider in Pyongyang and may not be completely easy with the way politics works there.

Kim Jong-un

born in 1983 or early 1984

youngest son of Kim Jong-il and his late third wife, Ko Yong-hui

went to school in Switzerland before returning home and attending the Kim Il-sung Military University

in July 2012, state media announced Mr Kim was married to "Comrade Ri Sol-ju"

succeeded his father as supreme leader following Kim Jong-il's death on 17 December 2011

Image 'mismanagement'

Over the years, many outside experts have seen a logic to North Korean policy - blood-curdling rhetoric is cranked up when the regime needs foreign help.

But there's been a lack of purpose about Kim Jong-un's actions. "I couldn't tell you what his foreign policy is," says Mr Foster-Carter. "One moment, he's leaving for Russia, and then he cancels." He closed down the industrial zone on the border with South Korea to no obvious purpose: "He pulled workers out of Kaesong. Why?"

Another of the most astute and nuanced experts on North Korea is similarly unconvinced by Kim Jong-un's performance in his first three years in the job.

North Koreans expect to see foreigners bow in front of their leaders - former NBA player Dennis Rodman did not

Brian Myers teaches at Dongseo Unviersity, in Busan, in South Korea. He is the author of The Cleanest Race, a book about propaganda in North Korea, and told the BBC: "With Kim Jong-un, I do get the impression that he's not his father's intellectual equal. I think he's done a terrible job at managing his own image."

This matters in North Korea. "North Koreans are not looking as critically at him as we are, but they're not fools. They are a much more sophisticated people than we think. He's simply too young and unsophisticated and too un-parental in his demeanour to exert the same kind of charisma on his people as his father did."

Mr Myers cites the visit of the American basketball player Dennis Rodman as a miscalculation: "Pictures of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il receiving foreigners always showed the foreigners bowing and scraping and the leaders standing very straight as though the foreigners were not very important.

"In the film of Kim Jong-un meeting Dennis Rodman, you had this retired basketball player with his legs crossed, a can of Coca-Cola in front of him, sunglasses on and the baseball cap. You could see by the faces of the people sitting behind him that they were having difficulty trying to understand just what was going on.

"When I saw those film clips, it occurred [to me] that, perhaps because Kim Jong-un had grown up overseas, he was not in tune with the official culture.

"And that's going to cause problems for him down the road."

- Published13 May 2015

- Published13 May 2015

- Published11 September 2023

- Published19 July 2023

- Published13 December 2013