The beauty contest winner making Japan look at itself

- Published

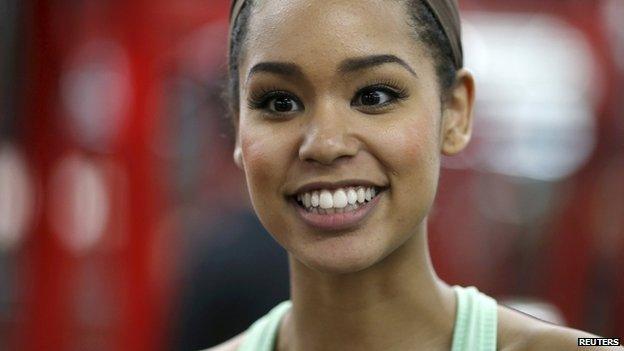

Miss Japan Ariana Miyamoto identifies herself as what is known in Japan as a "hafu", taken from the English word "half"

At first sight even I am a little confused by Ariana Miyamoto. She is tall and strikingly beautiful. But the first thing that pops in to my head when I meet the newly crowned Miss Universe Japan is that she doesn't look very Japanese.

In just two years here I have clearly absorbed a lot of the local prejudices about what it means to be "Japanese".

My confusion lasts only until Ariana opens her mouth. Suddenly everything about her shouts out that she is Japanese, from the soft lilting tone of her voice, to her delicate hand gestures and demure expression.

Well of course she is. Ariana was born in Japan and has lived here all her life. She knows little of her father's home back in Arkansas in the United States. But to many Japanese, and I really do mean many, Ariana Miyamoto is not Japanese. Not fully anyway.

Ariana is what is known in Japan as a "hafu", taken from the English word "half". To me the word sounds derogatory. But when I ask her Ariana surprises me by defending the term, even embracing it.

Ariana says the 'hafu' term is essential to understand her

"If it was not for the word hafu, it would be very hard to describe who I am, what kind of person I am in Japan," she says.

"If I say I am 'Japanese' the reply would be: 'No, you can't be'. People will not believe that. But if I say I am 'hafu', people agree. There is no word like hafu outside Japan, but I think we need it here. In order for us mixed kids to live in Japan, it is indispensible and I value it."

In Japan the reaction to Ariana's victory has been oddly muted. While the international media are trooping to her door every day, the Japanese media has largely ignored her.

"I feel that I have more attention from outside of Japan," she says.

"I have more interviews with non-Japanese media compared to Japanese media. When I am walking down the street, no Japanese will come up to me, but I get lots of congratulations from non-Japanese tourists."

On social media the reaction has been mixed, with many Japanese expressing support and joy. But others have been much less pleasant, even hostile.

Ariana says the Japanese need to stop stereotyping

"Is it ok to select a hafu as Miss Japan," one person wrote on twitter.

"It makes me uncomfortable to think she is representing Japan," wrote another.

In much of the rest of the world identity is no longer defined by the way you look.

There are white, black, Asian and Chinese Britons, just as there are any number of different sorts of Americans. But Japan still clings to a very narrow definition of what it means to be "Japanese".

In part that is because this is still such an extraordinarily homogenous society. Immigrants make up just one per cent of Japan's population, and most of those are from Korea and China.

Centuries of isolation have also imbued Japan with a sense of separateness.

She has faced some hostile comments after her win

Many people here genuinely believe Japanese are unique, even genetically separate from the rest of us.

When my (Japanese) wife got pregnant, one of her friends congratulated her with the words: "It's not easy for us Japanese to get pregnant with a foreigner". I didn't know whether to laugh or cry.

Of course this myth is complete nonsense. Japanese are an ethnic hotch-potch, the result of different migrations over thousands of years, from the Korean peninsula, China and South East Asia. But the myth is strong, and that makes being different here hard.

Growing up in a small city in western Japan, Ariana experienced it at first hand. Her best friend at school killed himself in part because he couldn't face being treated as an outsider all the time.

"We used to talk a lot about how hard it was to be hafu," she says.

She hopes her victory is a sign that her country is changing

"He wanted to talk about why we are excluded from others three days before he died.

"He used to say it was very difficult for him to live. He could not speak any English. People used to wonder why he did not speak any English despite his looks - he looked very foreign to them."

Ariana's victory is, perhaps, a sign that Japan is finally, slowly starting to change. That is certainly what she hopes, and that her newfound fame may help other hafu children.

"I think the Japanese like to stereotype. But I think we need to change that," she says.

"There will be more and more international marriages and there will be more mixed kids in the future. So I believe we need to change the way of thinking for those kids, for their future."

She is certainly right about that. Ariana Miyamoto is part of growing trend in Japan. One in 50 new babies born here are now biracial, 20,000 babies a year. Japan is changing. Now how will it react if Ariana Miyamoto lifts the Miss Universe crown?

- Published18 March 2014

- Published29 October 2024