Will anyone help the Rohingya people?

- Published

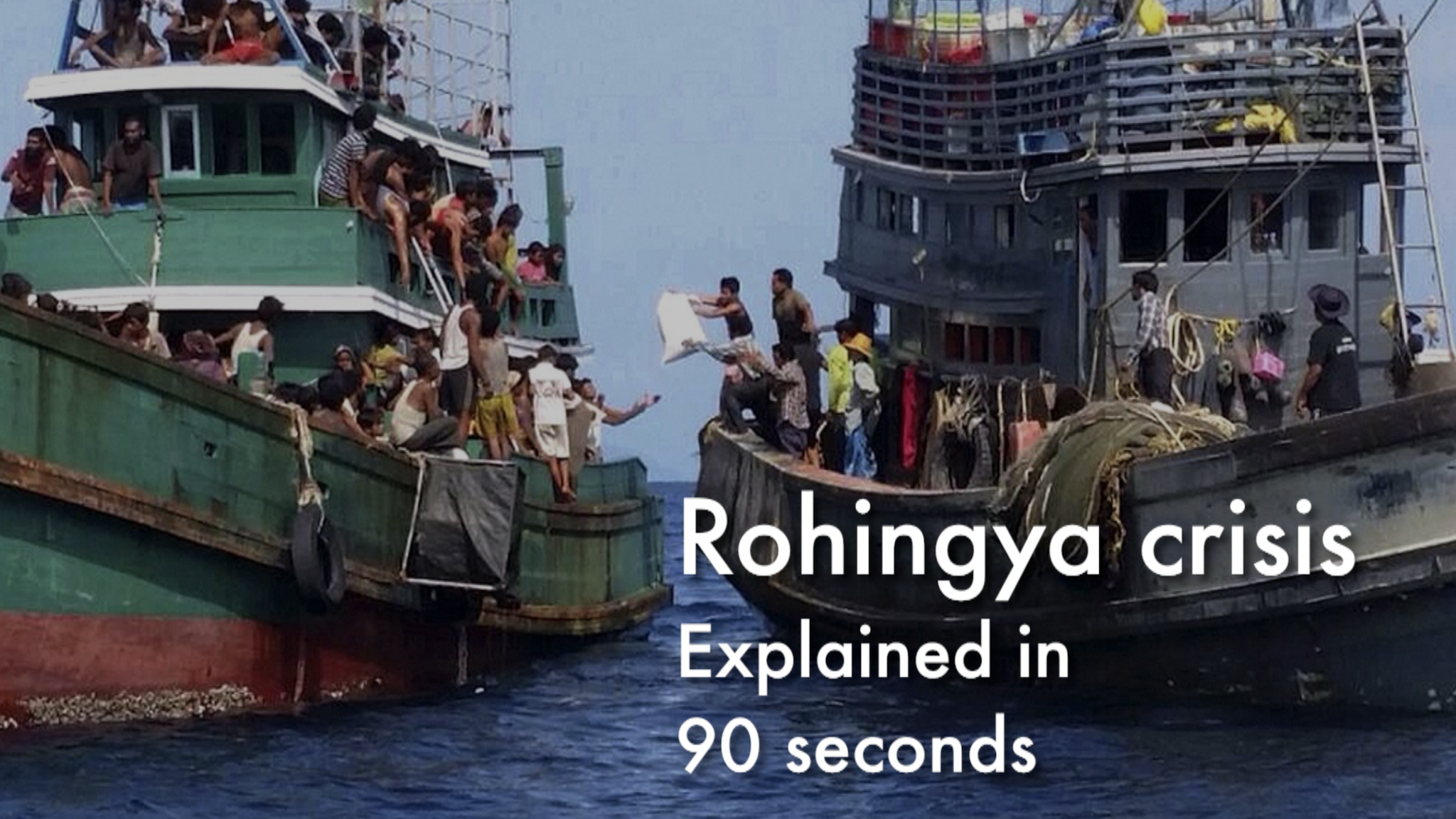

Rohingya migrants rescued from a fishing boat collect rain water at a temporary shelter

For decades, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have lived in Rakhine State, near Myanmar's border with Bangladesh.

Long denied citizenship and freedom of movement by the government of Myanmar (also known as Burma), shocking images have emerged in recent weeks showing hundreds of Rohingya migrants drifting at sea in fishing boats, as part of a failed attempt to leave for Malaysia.

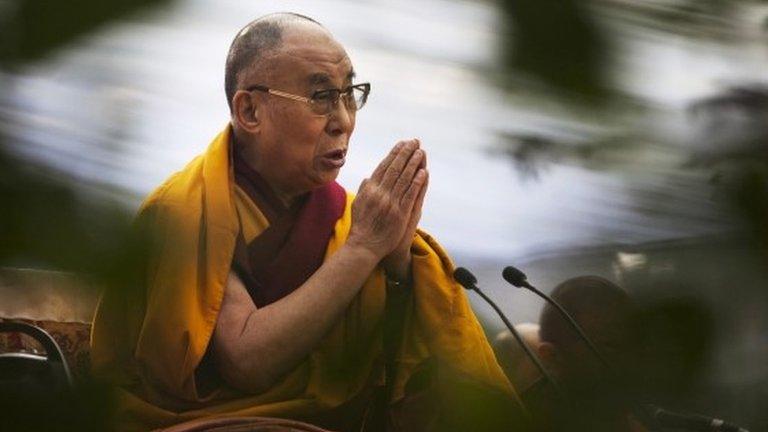

Thailand, which was being used as a smuggling route by people traffickers, has cracked down on the trade and a senior Thai officer has been charged in connection with trafficking. And the Dalai Lama has joined other international voices calling on Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to speak out about their plight.

Four experts discuss with the BBC World Service Inquiry programme who can and will help the Rohingya.

Tun Khin: Burma needs democracy

Tun Khin is president of the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK.

"My grandfather was a parliamentary secretary but I'm not a citizen. Your grandfather's grandfathers were there in your native land, but your citizenship is not recognised, so this is very frustrating, shocking and a tragic moment for all Rohingya, including me.

Thousands of Rohingyas are believed to be stranded at sea

"They were a recognised ethnic group [during] Burma's democratic period of time, 1948 to 1962. At that time, the Rohingya language was broadcast from Burma radio broadcasting programme. Unfortunately today Burma's government denies that the Rohingya exist."

Democracy in Burma ended with a military coup in 1962, and with it any official recognition of the Rohingya. In 1982, a new citizenship law was passed, consigning most Rohingya to a stateless existence. The government argues they are from neighbouring Bangladesh not Myanmar, and that the Rohingya identity has been invented by migrants to gain citizenship.

"This is just baseless accusation. It's hatred against Rohingya.

"Because of that law, today more than 1.3 million Rohingya are not citizens of Burma and are denied the right to have food, denied the right to have medical treatment, denied the right to have movement, denied the right to have children, denied the right to have education and [it leads to] state-sponsored violence against them, and burning down their houses and pushing them to the camps.

"We are struggling for human rights and democracy for Burma. When democracy comes one day, our situation will get better."

Aung Zaw: Aung San Suu Kyi has let Rohingya down

Aung Zaw is the editor of Irrawaddy Magazine, an independent publication banned in Myanmar until 2012.

"Personally I admire [Aung San Suu Kyi], professionally I question her, trying to make a very precise analysis about pros and cons of her leadership and her struggle for democracy. I think she disappointed a lot of people because of her silence, because of her status as South East Asia's Nelson Mandela. But she completely failed on [the Rohingya] issue.

Aung San Suu Kyi has come in for criticism

"Aung San Suu Kyi is no longer a human rights activist, as we saw her 20 years ago when she was under house arrest. Aung San Suu Kyi has changed. This is different Aung San Suu Kyi, a new Aung San Suu Kyi. She will not do anything to help the Rohingya.

"Whenever I engage with even close friends and my colleagues about the issue of Rohingya, the conversation will become very volatile. It could change the friendship because people will take it very sensitively. It's very sad.

"In the newsroom that could be a very hot topic among the editors and reporters who are very shy to speak of these sensitive issues or who reject completely that this sort of story should be reported.

"I think it's a very deep prejudice against Muslim minority populations in our country. This has not just happened now, it has been a long-held view."

Mahfuz Anam: Not Bangladesh's responsibility

Mahfuz Anam is editor of the Daily Star, the most popular English language daily amongst Bangladesh's 150 million people.

"Bangladesh is the most populous country in the world, we are among the smallest land mass with the highest density of people in the world. It's not like a case of, 'OK, some people have come so let's settle them'.

Migrants at a Rohingya camp in Teknaf, Bangladesh

"They [the Rohingya migrants] trickle out into the rest of the society looking for some ways to make their living. So there is a constant phenomenon of them overflowing into other areas and then basically creating competition for jobs, which creates local unrest.

"They are housed, they have rudimentary education, living facilities and they are here safe, they are not being persecuted. You have to give us the credit of treating them in a humane way with the hope that the repatriation process comes through.

"Frankly, we can only be their host for the time being so that they can go back, but giving them citizenship, why?

"These people have been living in Myanmar for eight, nine centuries, and that's their home. They happen to be Muslims, but there are Muslims all over the world. These people have their rights, they have their own cultural groups, they have their history. People are rooted to their lands and their homestead.

"As a host country I think we are already helping them but, yes, more international help, more international focus I think is welcome."

Gwen Robinson: International community must play a 'delicate game'

Gwen Robinson is chief editor of the Nikkei Asian Review and has travelled to Rakhine State many times.

"The most striking thing, when you visit Rakhine State almost anywhere, but particularly in Sittwe, the capital, is this deep and abiding hatred, or just complete rejection of the Rohingya as people who belong there in any way.

"A lot of people forget that prior to the eruption of violence in 2012, the Rohingya ran the markets, they brought produce to town, they worked very hard. So, it wasn't exactly loving co-existence, but it was a reasonably peaceful co-existence.

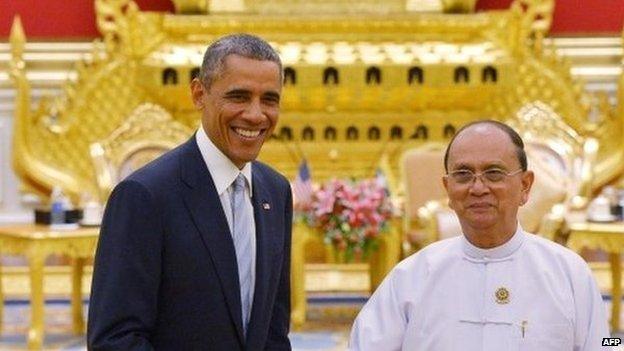

US President Obama was "optimistic" about reform after meeting Myanmar President Thein Sein in 2014

"When Obama came and gave a speech to students at Yangon University, that was like the second coming. People were so proud. That is a very powerful tool or lever.

"It's very clear that there's a great sense of face in Myanmar; they're very sensitive to going back to the pariah status they had before.

"We've had the Myanmar navy, for example, rescuing a couple of boats recently. They agreed broadly to try and address the root causes of the problem, which are actually a lot harder to follow up on, but Myanmar has shown some sign of willingness to co-operate a little. Which is a big advance on last year.

"I think the US engagement with Myanmar was partly driven by concerns that Myanmar was more or less seen as a vassal state of China's, in China's sphere of influence. Its location is extremely strategic, right in the heart of a very volatile area. It's got a lot of resources, it's got gas.

"There's a big incentive to keep Myanmar on side, so not just beat it senseless about the Rohingya, and slap sanctions on to maybe alienate Myanmar. [The US] has to play a very delicate game.

"There is no clear, easy solution. It will require that elusive thing, which doesn't exist at the moment, which is political will on the part of any leadership, now or in the future, to go down that route, and that would require a lot of courage that is highly unlikely for anyone who's going to adopt a policy of extending citizenship to these widely reviled people."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published28 May 2015

- Published24 May 2015

- Published20 May 2015