Will talks with the Taliban deliver a peace dividend?

- Published

The Taliban have maintained their campaign of violence despite rumours of peace talks

Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar has backed peace talks with the Afghan government in a new statement. The BBC's M Ilyas Khan in Islamabad assesses whether the announcement is a significant breakthrough.

When Sartaj Aziz, a Pakistani advisor on security and foreign affairs, claimed in May that Taliban officials had met the Afghan government negotiators for preliminary talks in Urumqi, China, the Taliban's response was emphatically cold.

Their spokesman, in a statement, feigned ignorance about such talks, adding that, if they did take place, they were held by people acting in their individual capacities.

But a different tone appeared to emerge from the militants after negotiations in Murree last week.

The Taliban spokesman did not dismiss the talks as an act of individuals. This time the emphasis was switched to the legitimacy of future talks, which he implied would have to be routed through the Taliban's Qatar office.

'Real power'

Coming against this backdrop, Mullah Omar's statement through a text message on a Taliban website does not make a specific reference to the Murree talks.

Afghan forces are now responsible for maintaining security following drastic reductions in Nato personnel in the country

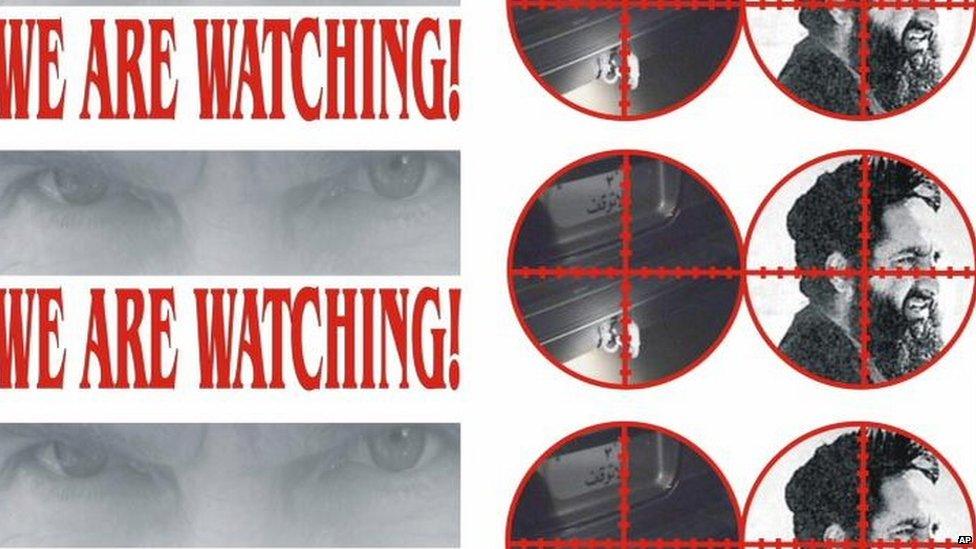

Mullah Omar has maintained a low profile despite US efforts to capture him - on one occasion American planes even dropped leaflets in Taliban areas detailing his car number plate

But it is evidence that the Taliban are not distancing themselves from the idea of holding peace talks with Afghanistan any more - they may even be actively pursuing such a dialogue.

In the past, the Taliban have scoffed at suggestions that talks should be held with the Afghan government, saying they could only talk to the Americans because they were the ones who held real power in the country.

Analysts say that with Nato's presence in the county drastically reduced, the Taliban mainly face two types of pressure.

One comes from Pakistan, which mid-wifed the birth of the Taliban movement in the early 1990s.

It provided them and their families with ideological support and sanctuaries on Pakistani soil after the American-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

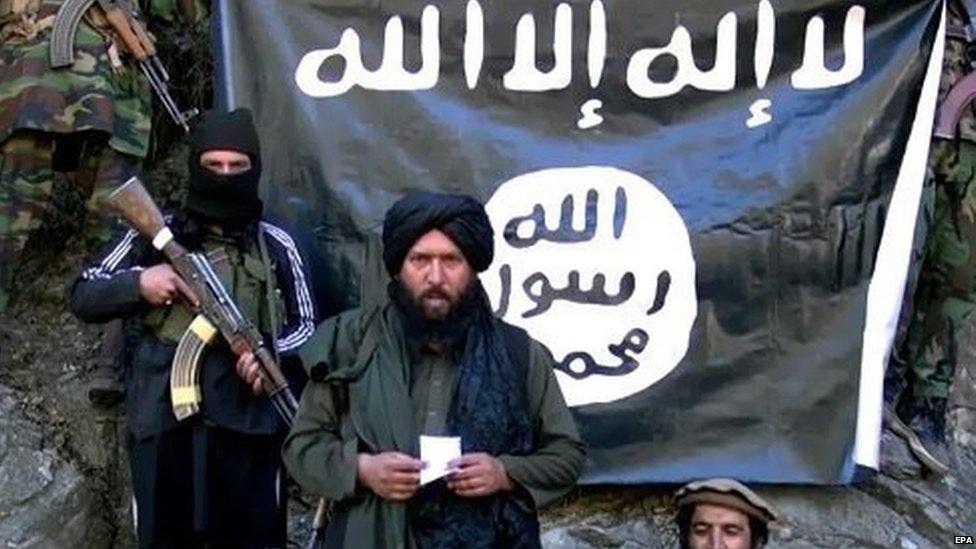

Islamic State militants are widely reported to be making in-roads in Afghanistan at the expense of the Taliban

Pakistan appears determined to play one Taliban faction off against another

Like the mujahideen who fought the Russians before them, Pakistan treated the Taliban as their proxies to fend off what they perceived as growing Indian influence over Afghanistan.

But the Pakistani position suffered a setback when the militant network it helped to create started to spawn groups that were opposed to Pakistan itself.

The government in Islamabad suspected that these groups could be used against Pakistan by "hostile" countries like Afghanistan, India or even some Western powers.

Initiatives in recent months by Pakistan to dismantle the militant infrastructure in the north-west of the country have received a fillip from China.

Beijing has has offered to plough huge amounts of money into a major economic corridor connecting this region with north-western parts of China and on to the Arabian Sea.

Rival militant franchise

Pakistan now appears determined to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table, though it may continue to play one Taliban faction off against another so that it can continue influencing the course any dialogue takes.

The second pressure comes from Islamic State, a rival militant franchise that is winning allies in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region on the grounds of speculation that overall Taliban leader Mullah Omar is dead, and that Taliban militants themselves are the lackeys of Pakistani intelligence.

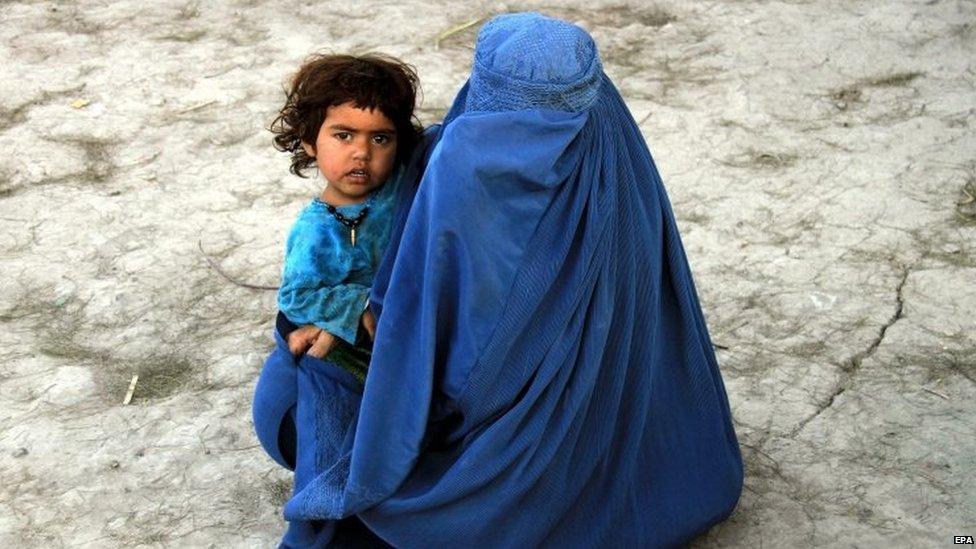

The years of conflict in Afghanistan have taken a terrible toll on the country's civilian population

Mullah Omar has not been seen in public since the end of 2001, and this absence has been quoted as a reason for the defection to Islamic State by various Afghan Taliban commanders, some elements of the Pakistani Taliban and long-time Taliban allies such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).

Mullah Omar's statement may now be used by his followers and sections of the Pakistani establishment to dismiss rumours of his death - especially prevalent among Taliban field commanders - as greatly exaggerated.

But critics may point out that, in the absence of a video or audio message, a mere text message is not enough proof of life and does not necessarily show that he is alive and well.

But it has to be remembered that Mullah Omar often issues written messages to mark religious occasions and has rarely, if ever, released a video or audio message.