Myanmar's 2015 landmark elections explained

- Published

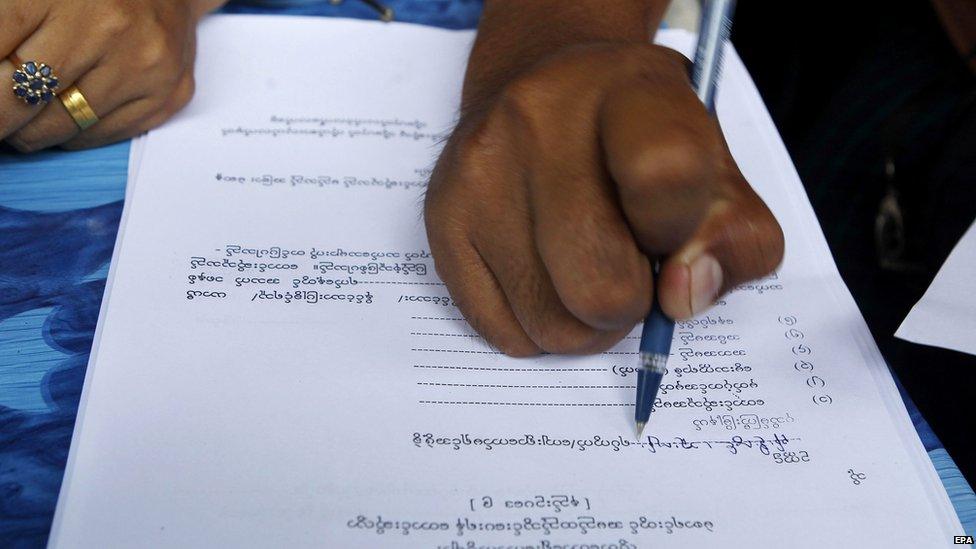

Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) has won a landslide victory in Myanmar after general elections on 8 November. It was the country's first national vote since a nominally civilian government was introduced in 2011, ending nearly 50 years of military rule. The NLD will control the next parliament and can choose the next president. The BBC explains the complexities behind the historic win.

Was the vote democratic?

As expected there were irregularities but while not entirely "free and fair" all observers accepted that the process was credible and the result reflect the will of the people.

That's not to say that Myanmar has a full democracy. Not all the seats in the Hluttaw (parliament) were up for grabs.

The military-drafted constitution guarantees that unelected military representatives take up 25% of the seats in the Hluttaw and have a veto over constitutional change. This is what the generals call "disciplined democracy".

Did we expect Aung San Suu Kyi's party to do so well?

The NLD remains popular in many areas of Myanmar

No-one was sure how much support the NLD would get. There were no reliable opinion polls so the only precedents were the two previous occasions that the party's popularity has been put to the test: the annulled 1990 general election and the by-elections of 2012.

In 1990 the NLD won 392 of the 492 available seats, taking 52.5% of the national vote.

What was remarkable about the 2015 result was that in both 1990 and then 2015 the NLD took almost exactly the same percentage of contested seats - just under 80%.

What's different this time is that the military had already ensured their continued political role by awarding themselves 25% of all the seats in parliament and putting other safeguards in the constitution.

How did the NLD win a landslide?

Ms Suu Kyi's party needs to gain votes in minority ethnic states to have a chance of winning a majority

First-past-the-post (constituency based) electoral systems like Myanmar's make landslides more likely.

It was always likely that the NLD would perform well in urban areas like Yangon, and in regions dominated by the ethnic Bamar majority.

What surprised many was that the NLD did so well in rural areas (where the military backed USDP had been expected to win seats) and also in ethnic minority areas like Kachin where people had expected smaller identity-based parties to do well.

How will the next president be chosen?

President Thein Sein has not ruled out remaining in politics

Indirectly. The 2008 constitution sets out a complex process whereby the Hluttaw chooses a president. Though the general election was in November it's likely to be March 2016 before this takes place.

Firstly the Hluttaw will divide into three groups: the elected representatives of the Lower House, the elected representatives of the Upper House, and the unelected army representatives.

Each group puts forward a candidate and then the three of them face a vote in a joint session, that includes all the elected and unelected representatives of both Houses.

The winner becomes president and the two losers vice-presidents.

Given the scale of the NLD win they will be able to nominate two of the three vice presidents and then ensure that their choice takes the top job.

Could Aung San Suu Kyi become president?

Aung San Suu Kyi may well have led her party to a landslide win but she can't become president.

Article 59F of the constitution states that if one of your "legitimate children… owes allegiance to a foreign power" you are disqualified. That covers both Ms Suu Kyi's sons Kim and Alexander, who have British passports.

Changing the constitution is impossible without the support of the unelected army representatives.

There are still a few who think that when confronted by the size of the NLD victory the army might change its mind. It's certainly possible that Ms Suu Kyi might be nominated by her party, even if she didn't meet the constitutional criteria.

But a President Suu Kyi in 2016 would require an incredible about turn by the military and remains a long shot.

If not President Suu Kyi then who?

Who will be Myanmar's new president?

Aung San Suu Kyi's not given many clues away beyond saying it would be a civilian member of her party.

Names being circulated in the media include her personal doctor Tin Myo Win and the ageing founder of her party Tin Oo.

Given that Ms Suu Kyi has already said she will be "above" the president, she's likely to choose someone loyal to her, rather than someone with their own distinct vision for Myanmar's future.

Just how powerful is the president?

Not as powerful as you might think.

Key security ministries (defence, home affairs and border affairs) are selected by the head of the army, not the president, and there can be no change to the constitution without military approval.

One of the themes of the last five years has been the emergence of the Hluttaw as an important political force.

Now dominated by the NLD it means the party can push through whatever legislation it wants.

Reporting by Jonah Fisher in Yangon