Mullah Omar: The myth and the movement

- Published

Mullah Omar had not been seen in public since the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001

Whether or not Mullah Omar is dead or alive, his long absence from public view is posing a growing threat to the strength of his splintering Afghan Taliban movement.

"Where is Mullah Omar?" is a question sources say is being increasingly and angrily directed at the commander regarded as the acting head, Akhtar Mohammad Mansour.

Commander Mansour has long been reported to be fighting off threats to his authority from more hardline Taliban opposed to any peace talks, including Abdul Qayum Zakir.

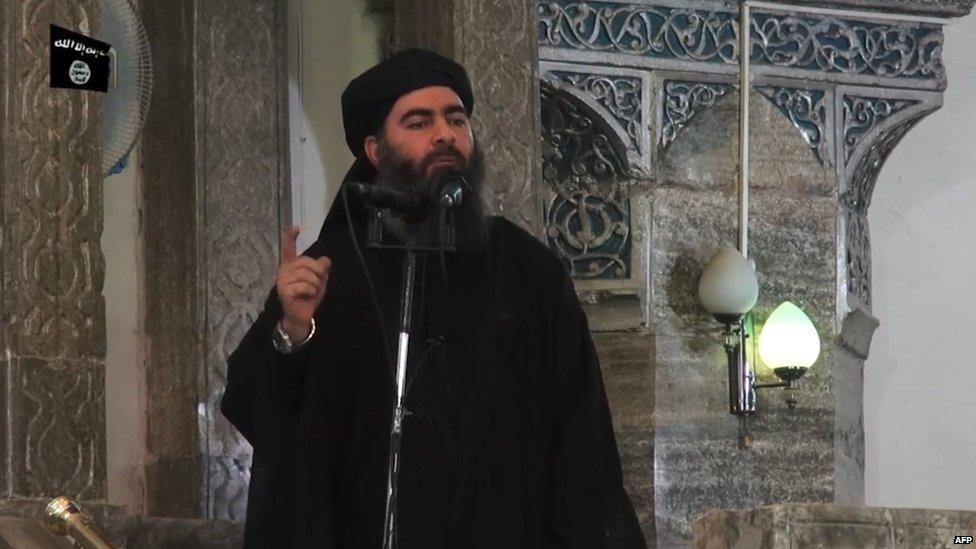

The Taliban are also facing a growing challenge from the still small, but increasingly significant presence of the so-called Islamic State in Afghanistan. Videos have emerged of disgruntled Taliban fighters swearing allegiance to the IS's self-declared Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The Iraqi cleric, who also declared a modern day caliphate in areas under IS control in Iraq and Syria, has publicly mocked the religious and political leadership of Mullah Omar.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State militia, has ridiculed Mullah Omar's leadership

Fragile unity

In a Taliban movement said to be founded on a pledge of allegiance to the Amir ul-Mumineen (Commander of the Faithful), Mullah Omar's authority was regarded as a binding force of political and military strength.

"I really hope peace talks are concluded before Mullah Omar dies," a former senior Taliban official nervously remarked to me several years ago with unexpected candour about the movement's leader. "When he's gone, it will be much harder to maintain Taliban unity," he admitted with palpable concern.

Our conversation, outside Afghanistan, took place at a time when Nato-led forces were killing many mid-level Taliban commanders in their operations in southern Afghanistan. That was raising concern that younger, more radicalised fighters, without a strong allegiance to the Taliban leader, would rise through the ranks and be hard to keep in line.

In 2010, when US diplomats first engaged in face-to-face talks with the Taliban through what later became known as the movement's Political Office in the Gulf state of Qatar, they first sought to establish that the Talibs were acting with Mullah Omar's authority. At the time, US diplomats involved in the process told me credible assurances were received that Syed Tayyab Agha, his former personal secretary, had his blessing.

That green light was, however, said to be strictly limited to negotiations with the Americans about Taliban prisoners and the presence of foreign troops in Afghanistan.

They eventually resulted in last year's swap of the remaining American soldier in Taliban captivity, Bowe Bergdahl, for five Taliban members held at Guantanamo Bay.

Negotiations through the Taliban's political office in Qatar had to be approved by Mullah Omar

Seal of legitimacy

This year, in the midst of a series of unprecedented informal meetings between the Taliban's Political Office and Afghan government officials, Taliban sources emphasised they still did not have formal authorisation from Mullah Omar to negotiate officially and openly with the Afghan government.

That again raised the most salient issue: how to get a ruling from a leader who has not been seen in public since late 2001 when the Taliban movement was ousted in Afghanistan after the attacks of 11 September. Even his recorded messages stopped several years ago.

Taliban officials often insisted their leader had to keep an exceptionally low profile because of US efforts to kill or capture him. But he was widely rumoured to be in Pakistan, despite Islamabad's denials. A senior Afghan official told me a few years ago that the Americans had confirmed to him that Mullah Omar was living in the southern Pakistani city of Karachi.

This month, a written message from Mullah Omar suddenly appeared, to mark the Islamic Eid Festival. It did not directly refer to a new separate process of peace talks being organised by the Pakistani government which represented the first publicly recognised formal talks.

But the text said "peaceful interactions with the enemies is not prohibited" under Islamic tradition. It led to speculation over whether the message had been written by Mullah Omar himself, or someone who wanted his seal of legitimacy.

Reports of the Taliban leader's death have circulated for years but these latest ones have now emerged just days before another round of peace talks in Pakistan is about to get under way at the end of this month.

They also come at a time of disagreement over who should represent the Taliban in any negotiations with the Afghan government.

Sources say Pakistani military intelligence officers, who have long had close ties to the Taliban, are urging Taliban field commanders they have worked with to come to the table instead of members of the Political Office in Qatar with whom they have had difficult relations.

Powerful figurehead

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, who has adopted a new policy of working closely with the Pakistan government and military on Taliban issues, is said to be giving Islamabad considerable leeway in a negotiating process making slow and indeterminate progress.

Before the first round of talks in the Pakistani hill resort of Murree in early July, Mr Ghani was said to be under mounting pressure to abandon his approach to Pakistan, which was markedly different from his predecessor Hamid Karzai's strained relations with Islamabad.

And there's the larger question of how committed Taliban commanders are to a political process when they continue to conduct bloody attacks not just against military and police targets but also brazen assaults on Afghan civilians everywhere from crowded markets to the country's national assembly.

Numerous countries are known to have been involved for years in secret and not so secret efforts to bring the Taliban to the table including China, Norway, Britain, and some private mediation groups.

The legitimacy conveyed by the mythical Mullah Omar was always regarded as essential even if the reclusive leader had long ceased to be involved in the day-to-day running of the movement.

Now the issue of who can replace such a powerful figurehead is emerging as one of the most significant challenges to its survival as a cohesive political and military force.