Mullah Omar death: Why is Pakistan silent?

- Published

Mullah Omar was not seen in public after 2001

The Taliban have confirmed that their leader Mullah Omar is dead, and are thought to have appointed Mullah Akhtar Mansour as the movement's official head.

But there has been an eerie silence in Pakistani quarters in the 24 hours since the Afghan government announced that Mullah Omar died in a Pakistani hospital in April 2013.

This was despite reports that the top leadership council of the Taliban had been meeting in the Pakistani city of Quetta to choose the successor.

Pakistan's state television has ignored the news for the most part since it first broke.

The private media mostly followed the BBC line, and held debates in which the usual ex-military analysts, while refraining from confirming or denying the death, focused on the timing of the leak, saying it was meant to defame Pakistan and undermine Taliban-Kabul talks, which Pakistan had been set to host.

Some even suggested the Indians might have forced the hand of the Afghan officials who leaked it to the BBC.

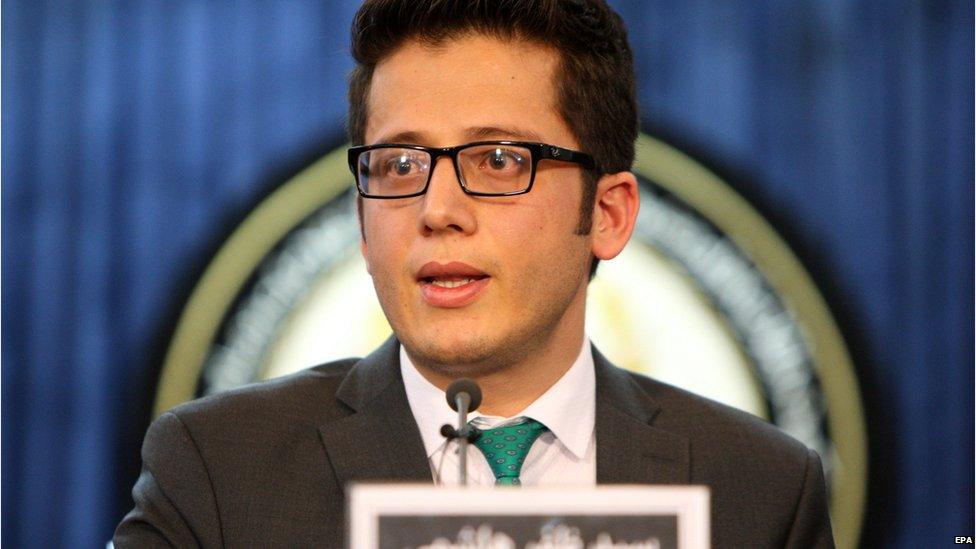

A day after Kabul's announcement, a Pakistani foreign office spokesman said he wouldn't like to comment on "rumours" of Mullah Omar's death.

Few are impressed at Pakistan's stance.

Osama Bin Laden was found and killed in Pakistan even though for years Pakistan denied he was present on its soil.

Osama Bin Laden was found and killed hiding in a compound in Abbottabad

Now Afghan intelligence officials have gone ahead with the claim that Mullah Omar died in the southern Pakistani city of Karachi.

While there may never be official Pakistani confirmation of this, few doubt claims that he lived most of his post-9/11 life in southern Pakistan.

The reason lies in the origin of the Taliban movement, and its symbiotic relationship with Pakistan.

The movement was originally confined to some parts of Kandahar province, and was mainly a localised reaction to extortion and moral crimes by local warlords.

But it gained strength in the later part of 1994 when Pakistanis dressed as madrassah students descended on the border town of Spin Boldak, busted a huge arms cache of a former mujahideen group, and then rolled up the Kandahar highway to free a Pakistani trade convoy to central Asia which had been held hostage by local warlords.

Subsequent years saw former mujahideen fighters joining the Taliban movement in their hundreds in a blitzkrieg in which the southern cities fell to the Taliban one after the other.

The Afghan government says Mullah Omar died in Pakistan

Security analysts in Pakistan and the US have long held that Pakistan provided the Taliban with logistics and tactical leadership to capture such important regional centres as Herat in the west, Jalalabad in the east and finally Kabul in 1996.

Post-9/11, when the US-led coalition dislodged the Taliban regime, Pakistan allowed the fleeing militants to carve a sanctuary on its soil in the border town of Wana in South Waziristan tribal district.

This sanctuary later expanded to an entire north-western belt along the Afghan border, called the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata).

This played a major role in the Taliban's ability to survive, and finally take the battle to the US-led coalition troops inside Afghanistan.

All this while, and despite Pakistan's denials, it was common knowledge the entire Taliban leadership set up bases in Quetta and Peshawar, and later in Karachi, from where they guided operations inside Afghanistan.

After the end of Nato's mission in Afghanistan last year, Pakistan moved to clear these sanctuaries of unwanted groups that the Taliban-al-Qaeda militant network had spawned over a decade.

Afghanistan has increased security following the announcement of Mullah Omar's death

In recent months, it has also reverted to securing peace in Afghanistan, without which it cannot successfully implement a major economic corridor the Chinese are building across the length of the country to connect China with the Arabian Sea.

But Pakistan's need to keep Indian influence out of Afghanistan continues to cause suspicions among some sections of Afghan ruling circles, who believe Pakistan will manipulate peace talks to achieve its own objectives at the cost of Afghan interests.

Many believe the Pakistanis would have kept Mullah Omar's death a secret in order to prevent rifts within Taliban.

Meanwhile, Pakistani officials believe that the Afghan intelligence service, the NDS, has been leaking news of the Taliban's engagement with Kabul to embarrass the Taliban leadership and to encourage defections from their ranks.

They feel by confirming the news of Mullah Omar's death on Wednesday, the NDS pushed President Ashraf Ghani, who was opposed to making the news public, into a corner.

Whether this move by the NDS will achieve peace in Afghanistan is a question only time will answer, but many believe that the Taliban movement will no longer be the monolithic force it remained until about three years ago.

And the NDS will also now be able to sell their long-held view to domestic and international audiences that the Taliban leadership is but a lackey of Pakistan.