The Pakistani hangman and his family tradition

- Published

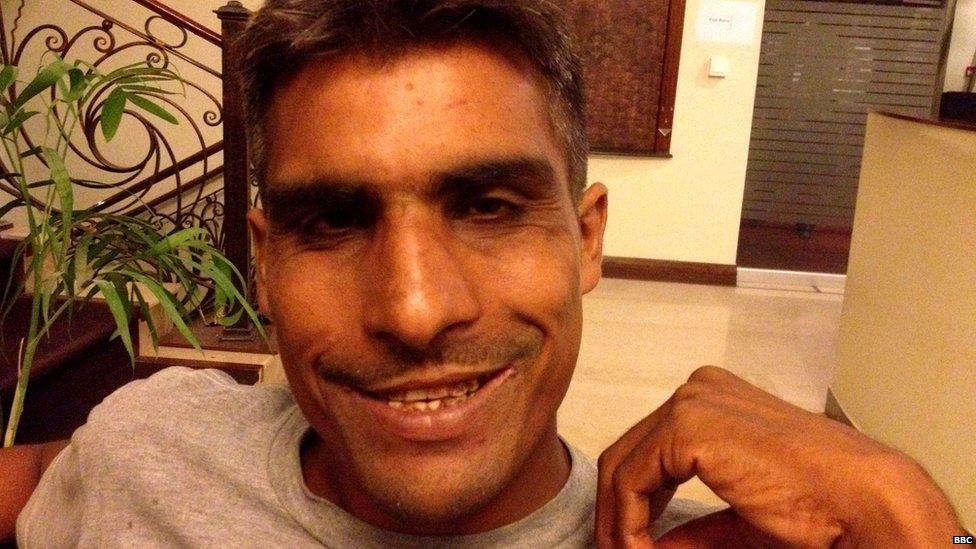

Hangman Sabir Massih: "My father... taught me to tie the noose"

A day after Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif announced the end of a seven-year moratorium on executions last year, Sabir Masih found his house surrounded by the paparazzi in Lahore.

The hangman had encounters with reporters and cameramen before, and would have been happy to share his views on the resumption of hangings on camera, but he was running out of time.

"I had to reach Faisalabad by the evening of 18 December because they had lined up two convicts for hanging early next morning," he recalls.

So he threw some clothes in a small shoulder bag, then put on the clothes of his 17-year-old sister, covered his face in a veil and walked right past the TV broadcast vans outside his house to reach the bus stop.

Just around that time, some 170km (105 miles) to the west, security forces in Faisalabad were taking the two convicts from the city's central jail, which has no gallows, to the district jail.

These were no ordinary convicts.

Mohammad Aqeel, alias Dr Usman, had led the audacious 2009 assault on army headquarters in Rawalpindi in which 20 people were killed, while Arshad Mehmood had been convicted for a 2003 assassination attempt on then-President Pervez Musharraf.

Both were former soldiers and members of Pakistan's feared home-grown militant networks.

Moratorium lifted

Meanwhile when he got off the bus in Faisalabad and took a cab to the district jail, Mr Masih had to produce his official executioner's ID several times to get past the roadblocks the army and police had set up to pre-empt any revenge strikes by militants.

The next day, Aqeel and Mehmood became the first men to be executed in Pakistan in seven years, and it was the 32-year-old Mr Masih who was the hangman.

Some recent executions, such as of Shafqat Hussain, have been particularly controversial

There are about 8,000 people on death row in Pakistan, more than any other country in the world, and since December Pakistan has put to death about 200 of them - some convicted of terrorist offences, others of murder.

Some of the cases have raised concerns over justice. On Tuesday a 23-year-old man, Shafqat Hussain, was executed for a child murder he denied committing.

His lawyers argued to the end that he had been a boy at the time of the murder and a confession was tortured out of him in custody.

Since the moratorium was lifted, Mr Masih says he has hanged close to 60 people in more than half a dozen jails in Punjab province. (He was not involved in the execution of Shafqat Hussain, who was put to death in Karachi.)

Overall, he believes he has executed more than 200 men since 2007, a claim he makes without a hint of remorse in his voice.

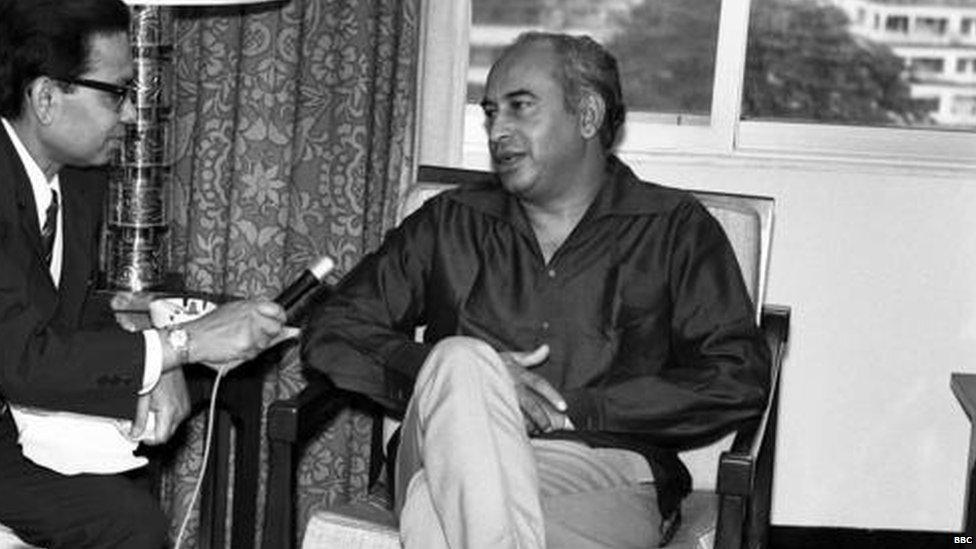

A member of the Masih family hanged Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (right) in 1979

This is probably because he belongs to a family of hangmen - the Pakistani equivalent of the Pierrepoints of Britain, Sansons of France, or Mammu Jallad's family in India.

Like most executioners from the times of the British Raj, Mr Masih is a Christian. His surname is the local name for Jesus, and is a common surname among Christians of the sub-continent.

He has sunken and heavily wrinkled eyes, teeth turned yellow from chewing tobacco and a heavy stammer in his speech, but a lean, 5ft 10in frame and bold facial features.

"Hanging is my family profession," he says. "My father was a hangman, and his father was a hangman, and his father and grandfather before him - since the times of the East India Company."

Perhaps his most famous ancestor is his grandfather's brother, Tara Masih, the man who hanged Pakistan's first elected prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, in 1979.

Tara Masih had to be flown from Bahawalpur to Lahore for the hanging because the executioner in Lahore, Sadiq Masih, Tara's nephew and Sabir's father, excused himself from hanging the popular leader.

Sabir also says that his grandfather, Kala Masih, hanged Bhagat Singh, a socialist revolutionary and hero of the Indian freedom movement, in 1931.

But there's a counter claim from members of Mammu Jallad's family in India who say Bhagat Singh was hanged by Ram Rakha, Mammu's grandfather.

'I feel nothing'

With this kind of family history, Sabir Masih is dogged by journalists looking for insight into his job, with questions like, do you get sleep the night before you are scheduled to hang a convict? Do you get nightmares afterwards? What did you feel when you hanged your first victim? How do your family and friends view your job?

"I feel nothing. It's a family thing. My father taught me how to tie the hangman's knot, how many coils etcetera, and he took me along to witness some hangings around the time when I was being recruited."

"My only concern is to prepare him at least three minutes before the time of hanging"

His first solo hanging was in July 2007.

"The only thing that made me nervous was to get the knot right, but the deputy chief of the jail told me not to worry.

"He made me tie and untie the knot a number of times before the convict was brought to the gallows. When the jailer waved his hand for me to pull the lever, I was focused on him, and didn't see the condemned man fall through the trapdoor."

It's more or less the same now.

The condemned prisoner "is read the charges by a magistrate, asked to bathe and offer prayers if he wants, and then walked to the gallows by the jail guards.

"My only concern is to prepare him at least three minutes before the time of hanging. So I remove his shoes, put a hood on his face, tie his hands and feet, put the noose around his neck, make sure the knot is placed below his left ear, and then wait for the jailer's signal to pull the lever."

There is no pre-or post-hanging psychological counselling for hangmen, and no limit to the number of hangings one executioner may perform before he is given a break.

Mr Masih says he doesn't need either.