How the Uighurs keep their culture alive in Pakistan

- Published

Insa Khan left Xinjiang as a child but still feels on the fringes of life in Pakistan

Insa Khan was only a few years old when she left Xinjiang, and has profound memories of the journey she made with her parents in 1949.

It took them about 50 days to walk through snow-capped mountains with donkeys carrying their luggage.

"My parents decided to leave Kashgar after Xinjiang officially became part of communist China," she said.

"I was too young to understand politics at that time," she added, as she served tea in the traditional Uighur way, with everybody sat on mats in the kitchen.

Insa is now 71 years old and has spent most of her life living in Gilgit, in Pakistan-administered Kashmir in the north.

As a Muslim, she has religious freedom.

And due to strong ties between China and Pakistan, she can also visit relatives in the autonomous Chinese province of Xinjiang.

But she has never thought of returning home.

"This place is my home now and my identity," said Insa Khan. "What would I go back to?"

Despite that certainty, she still feels an outsider in her adopted country.

Over a cup of tea, she tells me that some people have illegally occupied her land.

"They are Pakistani and I'm an immigrant so I didn't contact the police or file a complaint in the courts," she said, keeping her face veiled despite being at home.

"I'm alone so I can't risk a dispute with anyone here," she added.

Ancient ties

Insa is one of a few thousand Uighur Muslims who live in Gilgit.

The community is a mix of generations.

Some left Xinjiang and the thriving trading town of Kashgar in 1949, while others are later arrivals.

All say they were forced to leave as they were the victims of cultural and religious oppression in China.

China says its development projects have brought prosperity to Xinjiang's big cities.

However, development in Xinjiang is under government control and ownership, and Uighur Muslims point to numerous restrictions that prevent them from celebrating their Muslim culture and rituals.

Abdul Aziz was among those in the first wave to leave Xinjiang.

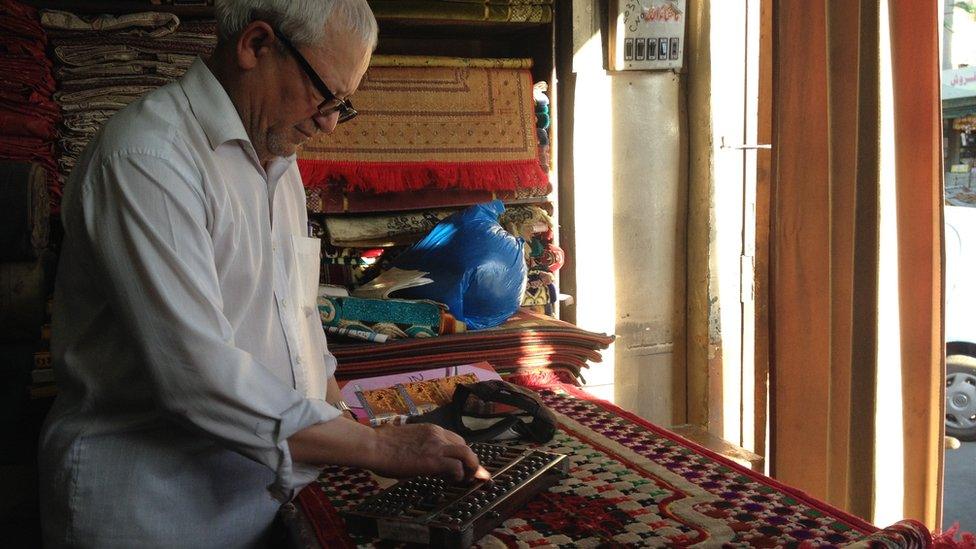

Though in his late 70s, he still works selling traditional Kashgari quilts and mattresses from his two shops on the busy airport road in Gilgit.

Abdul Aziz still uses a traditional Chinese calculator or abacus despite living in Pakistan for more than 60 years

His grandfather was a trader who used to travel between Gilgit and Kashgar in the 1940s.

Sitting on a small bench, Abdul Aziz reflects for a few moments before narrating his migration story.

"It was a very harsh journey," he said.

"We travelled for weeks in the mountains before we arrived here."

"When Mao Zedong took power and Xinjiang became part of his empire, they closed all the borders, and the Uighurs who were here couldn't return home."

"So my grandfather asked the rest of the family to leave Kashgar and migrate to Gilgit," he added.

He's now raising the fourth generation of his family in Pakistan, though he's slightly concerned about their diminishing knowledge of the Uighur language and Kashgari culture.

Abdul Aziz with his son and grandchildren

But he feels accepted in the local Gilgit community.

"People here have never made us feel like strangers," said Abdul.

"My business is good and my family is happy so what else can one wish for?" he added.

Unrest and uncertainty

But for Abdul Rahman Bukhari, secretary general of the Chinese Overseas Association, a representative body for Pakistani Uighurs, the unrest in Xinjiang is never far away.

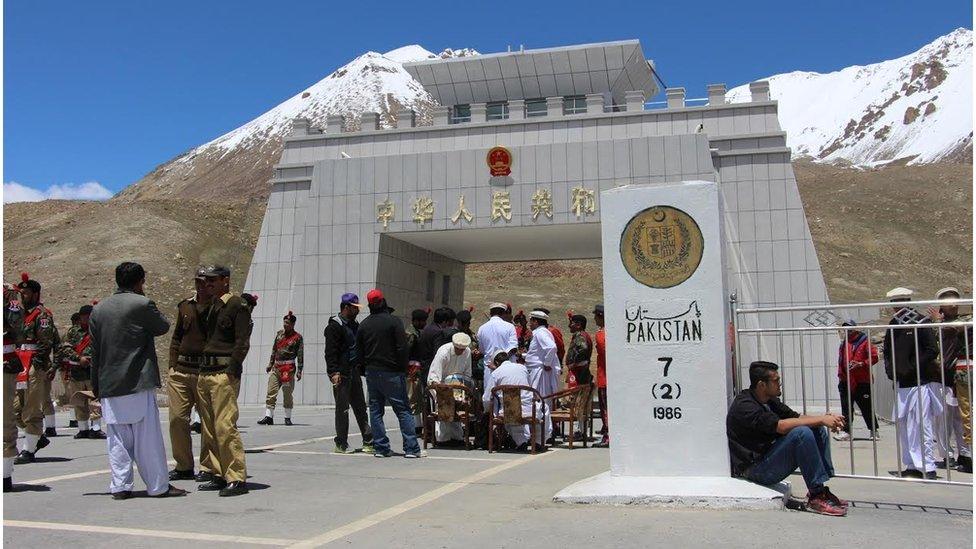

"We are sitting at a very sensitive location as it's the gateway between China and Pakistan," he said.

"Whenever there is trouble in Xinjiang, we feel the impact here."

Abdul Rahman Bukhari, third from the left, prays at the local mosque and says religious freedom is vital for Uighurs in Pakistan

China blames the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) for attacks in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China. It says Uighur militants are part of it.

It is also believed that ETIM militants have fought alongside the Pakistani Taliban in North and South Waziristan.

Mr Bukhari says China fears that Gilgit could become a gateway for ETIM sympathisers to send militants through to Xinjiang.

"They keep us under scrutiny, even by extending friendship and giving incentives for the community," he said.

China and Pakistan are deepening economic and security ties with Gilgit a vital gateway

"They want to make sure that Pakistani Uighurs can't be used by any militant group against Chinese interests."

Pakistani Uighurs can avail of generous support from China - Beijing offers to pay for their children's education in Pakistan, and gives selected people free trips to Xinjiang every year.

China also encourages Pakistani Uighurs to return to Kashgar with the offer of incentives to set up businesses and buy homes.

But almost nobody wants to go back.

"Xinjiang is much more developed than Gilgit so when we go there, for a moment we feel that we should return to our roots," said Mr Bukhari.

"But when we reflect, we realise that our ancestors have made the right choice as at least we have religious freedom in Pakistan."

But the religious freedom in Pakistan comes at a price, according to Mr Bukhari, who says the authorities ensure that it does not conflict with the strong strategic ties between Islamabad and Beijing.

"We hear the news about the crackdown on Uighurs in China but we can't do anything for them. We're helpless," said Mr Bukhari.

"In Pakistan, anyone can raise (their) voice for the Muslims of Palestine, Iraq and Afghanistan but Uighurs can't protest against Chinese atrocities against their brothers as the Pakistani authorities would never let us do that," he added.